A new study on the presence of pharmaceuticals in the world’s rivers discovered potentially toxic concentrations in more than a quarter of the locations studied. The new study examined 258 rivers around the world, including the Thames in London and the Amazon in Brazil, to assess the presence of 61 pharmaceuticals like carbamazepine, metformin, and caffeine.

The researchers studied rivers in more than half of the world’s countries, with rivers in 36 of these countries never having been tested for pharmaceuticals before. The research is part of the Global Monitoring of Pharmaceuticals Project, which has grown significantly over the last two years, with the new study becoming the first truly global-scale investigation of medicinal contamination in the environment.

With their latest study, the researchers found that:

- Pharmaceutical pollution contaminates water on all continents.

- Strong correlations between a country’s socioeconomic status and higher levels of pharmaceutical pollution in its rivers (with lower-middle income nations the most polluted)

- High levels of pharmaceutical pollution were found to be most positively associated with regions with a high median age as well as high local unemployment and poverty rates.

- The world’s most polluted countries and regions have received the least attention (namely sub-saharan Africa, South America and parts of southern Asia).

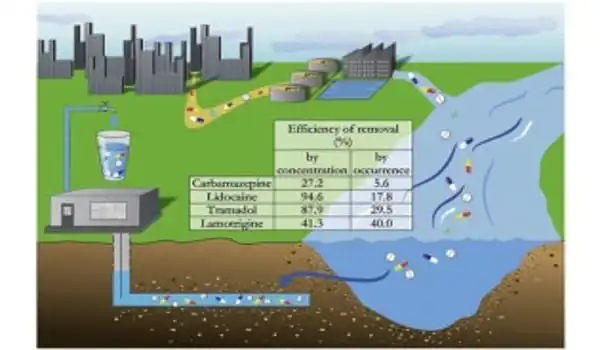

- The activities most associated with the highest levels of pharmaceutical pollution included rubbish dumping along river banks, insufficient wastewater infrastructure and pharmaceutical manufacturing, and the dumping of residual septic tank contents into rivers.

Our understanding of the global distribution of pharmaceuticals in the aquatic environment has been greatly expanded as a result of our project. This single study presents data from more countries than the entire scientific community was previously aware of: 36 new countries, to be exact, where only 75 had previously been studied.

Dr. John Wilkinson

The study found that a quarter of the sites had potentially harmful levels of contaminants (such as sulfamethoxazole, propranolol, ciprofloxacin, and loratadine). The researchers hope that by increasing monitoring of pharmaceuticals in the environment, they will be able to develop strategies to limit the effects that pollutants may have.

The Amazon, Mississippi, Thames, and Mekong rivers were all included in the study. Water samples were collected from locations ranging from a Yanomami Village in Venezuela, where modern medicines are not used, to some of the world’s most densely populated cities, including Delhi, London, New York, Lagos, Las Vegas, and Guangzhou.

Politically unstable areas such as Baghdad, the Palestinian West Bank, and Yaoundé, Cameroon, were also included. The climates where the samples were collected ranged from high altitude alpine tundra in Colorado to polar regions in Antarctica, as well as Tunisian deserts.

While previous studies have monitored active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) in rivers, they have ignored many countries, measured only a few contaminants, and used different analytical methods. As a result, quantifying the scope of the problem from a global perspective has become difficult.

The water sample was analyzed at the Centre of Excellence in Mass Spectrometry at the University of York. “With 127 collaborators across 86 institutions worldwide, the Global Monitoring of Pharmaceuticals Project is an excellent example of how the global scientific community can come together to tackle large-scale environmental issues,” said Dr. John Wilkinson of the Department of Environment and Geography.

“We’ve known for more than two decades that pharmaceuticals find their way into the aquatic environment, where they can affect the biology of living organisms. But one of the most significant issues we’ve encountered in addressing this issue is that we haven’t been very representative when monitoring these contaminants, with almost all of the data focusing on a few areas in North America, Western Europe, and China.”

“Our understanding of the global distribution of pharmaceuticals in the aquatic environment has been greatly expanded as a result of our project. This single study presents data from more countries than the entire scientific community was previously aware of: 36 new countries, to be exact, where only 75 had previously been studied.”

The researchers believe that their method could be expanded in the future to include other environmental media such as sediments, soils, and biota, allowing for the creation of global-scale datasets on pollution.

The data for specific rivers will be available in the publication’s supplemental information (via PNAS). It will also be made available on the website of the Global Monitoring of Pharmaceuticals Project.

The researchers used ‘predicted no adverse effect concentrations (PNECs)’ to determine where there is a risk of adverse effects (such as toxicity). If the team found a concentration in the environment that was higher than the PNEC, organisms living there could be adversely affected by the pharmaceutical. This can manifest in a variety of ways, depending on the pharmaceutical, the organism being exposed, and the concentration. Disrupted reproductive capabilities, altered behavior or physiology, and even changes in heart rate are examples.

Contaminants discovered at potentially hazardous concentrations include:

- propranolol (a beta-blocker for heart problems such as high blood pressure)

- Sulfamethoxazole (an antibiotic for bacterial infection)

- Ciprofloxacin (an antibiotic for bacterial infection)

- loratadine (an antihistamine for allergies).