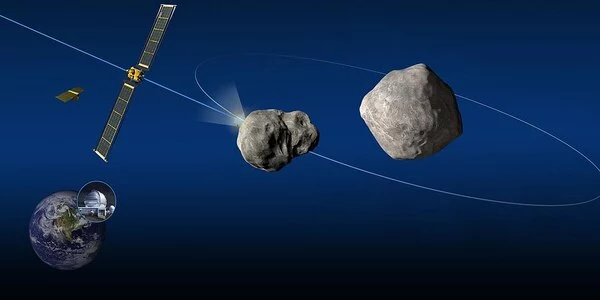

The DART mission was more successful than expected in adjusting Dimorphos’ trajectory, implying that a dangerous space rock could be deflected in the future. A spacecraft that collided with a small, harmless asteroid millions of miles away successfully altered its orbit.

It was successful! For the first time, humanity has purposefully moved a celestial object. NASA’s DART spacecraft shortened the orbit of asteroid Dimorphos by 32 minutes as a test of a potential asteroid-deflection scheme — a far greater change than astronomers expected.

The DART, or Double Asteroid Redirection Test, slammed into the tiny asteroid at approximately 22,500 kilometers per hour. The goal was to get Dimorphos closer to Didymos, the larger asteroid it orbits.

NASA took aim at an asteroid last month, and the space agency announced on Tuesday that its planned 14,000-mile-per-hour collision with an object named Dimorphos hit the target even more precisely than expected.

This is an extremely exciting and promising result for planetary defense. However, the change in orbital period was only 4%. It just gave it a little nudge.

Lori Glaze

This was the first winning strike of its kind. “We conducted humanity’s first planetary defense test,” NASA Administrator Bill Nelson said at a news conference, “and we demonstrated to the world that NASA is serious as a defender of this planet.”

Neither Dimorphos nor Didymos pose any threat to Earth. DART’s mission was to help scientists figure out if a similar impact could nudge a potentially hazardous asteroid out of harm’s way before it hits our planet.

The experiment was a smashing success. Before the impact, Dimorphos orbited Didymos every 11 hours and 55 minutes. After, the orbit was 11 hours and 23 minutes, NASA announced October 11 in a news briefing.

“For the first time ever, humanity has changed the orbit of a planetary body,” said NASA planetary science division director Lori Glaze.

Four telescopes in Chile and South Africa observed the asteroids every night after the impact. The telescopes can’t see the asteroids separately, but they can detect periodic changes in brightness as the asteroids eclipse each other. All four telescopes saw eclipses consistent with an 11-hour, 23-minute orbit. The result was confirmed by two planetary radar facilities, which bounced radio waves off the asteroids to measure their orbits directly, said Nancy Chabot, a planetary scientist at Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Md.

The minimum change for the DART team to declare success was 73 seconds — a hurdle the mission overshot by more than 30 minutes. The team thinks the spectacular plume of debris that the impactor kicked up gave the mission extra oomph. The impact itself gave some momentum to the asteroid, but the debris flying off in the other direction pushed it even more — like a temporary rocket engine.

“This is an extremely exciting and promising result for planetary defense,” said Chabot. However, the change in orbital period was only 4%. “It just gave it a little nudge,” she explained. Knowing that an asteroid is on its way is critical to future success. “You’d want to do it years in advance” to work on an asteroid headed for Earth, according to Chabot. One of many projects aimed at providing that early warning is the Near-Earth Object Surveyor, a planned space telescope.