According to new research, an international agreement to protect the ozone layer is expected to prevent 443 million cases of skin cancer and 63 million cataract cases for people born in the United States through the end of the century. The research team created a computer modeling approach that revealed the effect of the Montreal Protocol and subsequent amendments on stratospheric ozone, the associated reductions in ultraviolet radiation, and the health benefits.

The research team, comprised of scientists from the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR), ICF Consulting, and the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), focused on the far-reaching consequences of the Montreal Protocol, a landmark 1987 treaty, and subsequent amendments that significantly strengthened it. The agreement prohibited the use of chemicals that deplete ozone in the stratosphere, such as chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs).

Stratospheric ozone protects the planet from harmful levels of ultraviolet (UV) radiation from the Sun. To assess the long-term effects of the Montreal Protocol, the researchers devised a computer modeling approach that allowed them to look to the past as well as the future by simulating the treaty’s impact on Americans born between 1890 and 2100. The modeling revealed the effect of the treaty on stratospheric ozone, the associated reductions in ultraviolet radiation, and the health benefits.

In addition to the number of skin cancer and cataract cases avoided, the study found that the treaty, as most recently amended, will save approximately 2.3 million lives in the United States from skin cancer.

What is startling is what would have happened by the end of the century if the Montreal Protocol had not been in place. UV levels will have tripled by 2080. After that, our calculations for the health consequences begin to fail because we’re approaching conditions that have never been seen before.

Julia Lee-Taylor

“It’s very encouraging,” said NCAR scientist Julia Lee-Taylor, a study co-author. “It demonstrates that, given the will, the world’s nations can come together to solve global environmental problems.” The EPA-funded study was published in the journal ACS Earth and Space Chemistry. The National Science Foundation funds NCAR.

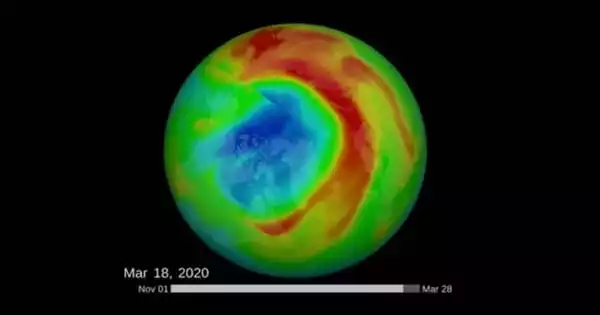

Mounting concerns over the ozone layer

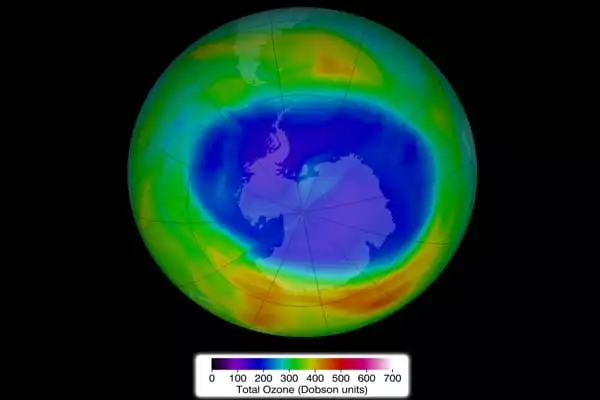

Scientists discovered in the 1970s that CFCs, which are used as refrigerants and in other applications, release chlorine atoms in the stratosphere, causing chemical reactions that destroy ozone. With the discovery of an Antarctic ozone hole in the following decade, concerns grew.

The loss of stratospheric ozone would be disastrous, as high levels of UV radiation have been linked to skin cancer, cataracts, and immunological disorders. The ozone layer also protects terrestrial, aquatic, and agricultural ecosystems.

The threat was met by policymakers with the 1987 Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer, in which nations agreed to limit the use of certain ozone-depleting substances. Subsequent amendments strengthened the treaty by broadening the list of ozone-depleting substances (such as halons and hydrochlorofluorocarbons, or HCFCs) and shortening the timetable for phase-out. The amendments were based on scientific community input, including input from a number of NCAR scientists, which was summarized in quadrennial Ozone Assessment reports.

The research team developed a model known as the Atmospheric and Health Effects Framework to quantify the treaty’s effects. This model, which draws on a variety of data sources related to ozone, public health, and population demographics, is comprised of five computational steps. These simulate past and future ozone-destroying substance emissions, the effects of those emissions on stratospheric ozone, the resulting changes in ground-level UV radiation, the exposure of the U.S. population to UV radiation, and the incidence and mortality of health effects caused by the exposure.

The results showed that under the amended treaty, UV radiation levels would return to 1980 levels by the mid-2040s. UV levels, on the other hand, would have continued to rise throughout the century if the treaty had not been amended, and they would have skyrocketed if there had been no treaty at all.

Even with the changes, the simulations show an increase in cataracts and skin cancers beginning with the onset of ozone depletion and peaking decades later as the population exposed to the highest UV levels ages. Those born between 1900 and 2040 have a higher risk of skin cancer and cataracts, with those born between 1950 and 2000 having the worst health outcomes. However, without the treaty, the health consequences would have been far worse, with cases of skin cancer and cataracts increasing at an alarming rate throughout the century.

“We drew away from disaster,” Lee-Taylor explained. “What is startling is what would have happened by the end of the century if the Montreal Protocol had not been in place. UV levels will have tripled by 2080. After that, our calculations for the health consequences begin to fail because we’re approaching conditions that have never been seen before.”

The research team also discovered that the later amendments to the treaty, rather than the original 1987 Montreal Protocol, were responsible for more than half of the treaty’s health benefits. Overall, the treaty avoided more than 99 percent of the potential health effects that would have resulted from ozone destruction. According to the authors, this demonstrates the importance of the treaty’s flexibility in adapting to changing scientific knowledge.

The researchers concentrated on the United States due to easy access to health data and population projections. According to Lee-Taylor, specific health outcomes in other countries may differ, but overall trends will be similar.