According to a study published today (September 13, 2021) in Hypertension, an American Heart Association journal, adults with normal blood pressure and high levels of stress hormones were more likely to develop high blood pressure and have cardiovascular events than those with lower stress hormone levels.

Endocrine glands produce stress hormones to alter one’s internal environment during times of stress. Many elements of brain function are modulated in a genetic manner by these. Profiling stress-responsive gene patterns might be valuable in generating novel functional hypotheses in order to better understand the molecular processes that underpin these stress hormone-mediated effects.

Stress hormones help the organism survive by performing a variety of duties such as mobilizing energy sources, raising heart rate, and downregulating metabolic processes that aren’t urgently required. Daily stresses, as well as catastrophic stress, have been demonstrated in studies to raise the risk of cardiovascular disease.

The stress hormones norepinephrine, epinephrine, dopamine, and cortisol can increase with stress from life events, work, relationships, finances, and more. And we confirmed that stress is a key factor contributing to the risk of hypertension and cardiovascular events.

Kosuke Inoue

The mind-heart-body link is a growing body of evidence that implies a person’s thinking can influence cardiovascular health, cardiovascular risk factors, and risk for cardiovascular disease events, as well as cardiovascular prognosis over time.

“The stress hormones norepinephrine, epinephrine, dopamine, and cortisol can increase with stress from life events, work, relationships, finances, and more. And we confirmed that stress is a key factor contributing to the risk of hypertension and cardiovascular events,” said study author Kosuke Inoue, M.D., Ph.D., assistant professor of social epidemiology at Kyoto University in Kyoto, Japan. Inoue also is affiliated with the department of epidemiology at the Fielding School of Public Health at the University of California, Los Angeles.

“Previous research focused on the relationship between stress hormone levels and hypertension or cardiovascular events in patients with existing hypertension. However, studies looking at adults without hypertension were lacking,” Inoue said.

“The impact of stress on individuals in the general population is relevant because it gives fresh information on whether routine stress hormone assessment should be considered to reduce hypertension and CVD events.”

MESA Stress 1 was a substudy of the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), a comprehensive investigation of atherosclerosis risk factors including over 6,000 men and women from six communities across the United States. White, Black, and Hispanic individuals with normal blood pressure from the New York and Los Angeles sites were asked to participate in the MESA Stress 1 substudy as part of MESA examinations 3 and 4 (conducted between July 2004 and October 2006).

Researchers looked examined the levels of norepinephrine, epinephrine, dopamine, and cortisol chemicals that respond to stress in this substudy. A 12-hour overnight urine test was used to determine hormone levels. There were 412 persons in the substudy, ranging in age from 48 to 87. About half of the participants were female, with 54 percent being Hispanic, 22 percent being Black, and 24 percent being white.

Participants were followed for three more visits (between September 2005 and June 2018) to see if they developed hypertension or experienced cardiovascular events including chest discomfort, the need for an artery-opening operation, or a heart attack or stroke.

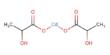

Catecholamines, such as norepinephrine, epinephrine, and dopamine, maintain stability throughout the autonomic nervous system, which controls involuntary physiological activities including heart rate, blood pressure, and respiration. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, which affects stress response, regulates cortisol, a steroid hormone secreted when one is stressed.

“Although all of these hormones are produced in the adrenal gland, they have different roles and mechanisms to influence the cardiovascular system, so it is important to study their relationship with hypertension and cardiovascular events, individually,” Inoue said.

Their study of the link between stress hormones and the development of atherosclerosis discovered that every time the levels of the four stress hormones doubled, there was a 21-31 percent increase in the probability of developing hypertension during a 6.5-year follow-up period.

Each doubling of cortisol levels was associated with a 90% increase in the risk of cardiovascular events over a median of 11.2-years of follow-up. There was no link between catecholamines and cardiovascular events.

“It is challenging to study psychosocial stress since it is personal, and its impact varies for each individual. In this research, we used a noninvasive measure a single urine test to determine whether such stress might help identify people in need of additional screening to prevent hypertension and possibly cardiovascular events,” Inoue said.

“The next big scientific topic is whether and in which groups stress hormone monitoring should be enhanced. Currently, these hormones are only evaluated when an underlying cause of hypertension or other associated disorders is suspected. We may wish to assess these hormone levels more regularly if further screening will help avoid hypertension and cardiovascular events.”

The study had one limitation: it did not include persons who had hypertension at the start of the trial, which would have resulted in a bigger sample group. Another restriction is that the researchers only utilized a urine test to evaluate stress hormones, and no additional stress hormone assays were employed.

Co-authors are Tamara Horwich, M.D.; Roshni Bhatnagar, M.D.; Karan Bhatt; Deena Goldwater, M.D., Ph.D.; Teresa Seeman, Ph.D.; and Karol E. Watson, M.D., Ph.D.

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, the Barbara Streisand UCLA Women’s Health Program, the National Institutes of Health, the Toffler Award at UCLA, and the Honjo International Foundation Scholarship all contributed to the research.