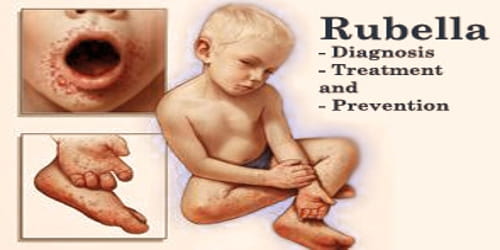

Rubella (Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prevention)

Definition: Rubella, which is also known as German measles, is a viral infection that causes a red rash on the body. It is not the same as measles (rubeola), though the two illnesses do share some characteristics, including the red rash. However, rubella is caused by a different virus than measles and is neither as infectious nor usually as severe as measles.

This disease is often mild with half of the people not realizing that they are infected. A rash may start around two weeks after exposure and last for three days. It usually starts on the face and spreads to the rest of the body. The rash is sometimes itchy and is not as bright as that of measles.

While rubella virus infection usually causes a mild fever and rash illness in children and adults, infection during pregnancy, especially during the first trimester, can result in miscarriage, fetal death, stillbirth, or infants with congenital malformations, known as congenital rubella syndrome (CRS).

The rubella virus is transmitted by airborne droplets when infected people sneeze or a cough. Humans are the only known host.

It is typically a mild infection that goes away within one week, even without treatment. However, it can be a serious condition in pregnant women, as it may cause congenital rubella syndrome in the fetus. Congenital rubella syndrome can disrupt the development of the baby and cause serious birth defects, such as heart abnormalities, deafness, and brain damage.

Rubella is preventable with the rubella vaccine with a single dose being more than 95% effective. Often it is given in combination with the measles vaccine and mumps vaccine, known as the MMR vaccine. When some, but less than 80% of the people are vaccinated, more women might make it to childbearing age without developing immunity by infection or vaccination and CRS rates could increase. Once infected there is no specific treatment.

The name “rubella” is from Latin and means little red. It was first described as a separate disease by German physicians in 1814 resulting in the name “German measles.”

Diagnosis and Treatment of Rubella: Rubella virus-specific IgM antibodies are present in people recently infected by rubella virus, but these antibodies can persist for over a year, and a positive test result needs to be interpreted with caution. The presence of these antibodies along with, or a short time after, the characteristic rash confirms the diagnosis.

Since German measles appears similar to other viruses that cause rashes, the doctor will confirm the patient’s diagnosis with a blood test. This can check for the presence of different types of rubella antibodies in the patient’s blood. Antibodies are proteins that recognize and destroy harmful substances, such as viruses and bacteria. The test results can indicate whether the patient currently has the virus or are immune to it.

No treatment will shorten the course of rubella infection, and symptoms are often so mild that treatment usually isn’t necessary. However, doctors often recommend isolation from others — especially pregnant women — during the infectious period.

Treatment of newborn babies is focused on management of the complications. Congenital heart defects and cataracts can be corrected by direct surgery.

In rare instances when a child or adult is infected with rubella, simple self-care measures are required:

- Rest in bed as necessary.

- Take acetaminophen (Tylenol, others) to relieve discomfort from fever and aches.

- Tell friends, family, and co-workers — especially pregnant women — about their diagnosis if they may have been exposed to the disease.

- Avoid people who have conditions that cause deficient or suppressed immune systems.

- Tell the child’s school or childcare provider that the child has rubella

Rubella infection of children and adults is usually mild, self-limiting and often asymptomatic. The prognosis in children born with CRS is poor.

Vaccination: The rubella vaccine is a live attenuated strain, and a single dose gives more than 95% long-lasting immunity, which is similar to that induced by natural infection.

Rubella vaccines are available either in a monovalent formulation (vaccine directed at only one pathogen) or more commonly in combinations with other vaccines such as with vaccines against measles (MR), measles and mumps (MMR), or measles, mumps and varicella (MMRV).

Doctors recommend that children receive the MMR vaccine between 12 and 15 months of age, and again between 4 and 6 years of age — before entering school. It’s particularly important that girls receive the vaccine to prevent rubella during future pregnancies.

Prevention of Rubella: For most people, vaccination is a safe and effective way to prevent German measles. The rubella vaccine is typically combined with vaccines for the measles and mumps as well as varicella, the virus that causes chickenpox. Two live attenuated virus vaccines, RA 27/3 and Cendehill strains were effective in the prevention of adult disease.

Babies who’ll be traveling to a country where rubella is common can get vaccinated as early as six months.

While the rubella vaccine usually isn’t harmful, the virus in the shot could cause adverse reactions in some people.

Information Source: