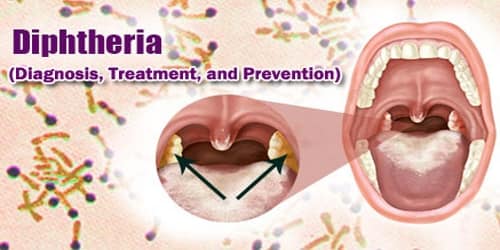

Diphtheria (Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prevention)

Definition: Diphtheria is an infectious disease caused by the bacterium Corynebacterium diphtheria, which primarily infects the throat and upper airways, and produces a toxin affecting other organs. Diphtheria is a disease of the past in most parts of the world.

The disease was first described in the 5th century BC by Hippocrates. The bacterium was identified in 1882 by Edwin Klebs.

The illness has an acute onset and the main characteristics are a sore throat, low fever and swollen glands in the neck and the toxin may, in severe cases, cause myocarditis or peripheral neuropathy. The diphtheria toxin causes a membrane of dead tissue to build up over the throat and tonsils, making breathing and swallowing difficult.

Diphtheria is usually spread between people by direct contact or through the air. It may also be spread by contaminated objects. Some people carry the bacteria without having symptoms, but can still spread the disease to others.

Medications are available to treat diphtheria. However, in advanced stages, diphtheria can damage our heart, kidneys and nervous system. Even with treatment, diphtheria can be deadly – up to 3 percent of people who get diphtheria die of it. The rate is higher for children under 15.

A type of bacteria called Corynebacterium diphtheriae causes diphtheria. The condition is typically spread through person-to-person contact or through contact with objects that have the bacteria on them, such as a cup or used tissue. People may also get diphtheria if they are around an infected person when they sneeze, cough, or blow their nose.

People who are at increased risk of contracting diphtheria include:

- Children and adults who don’t have up-to-date immunizations

- People living in crowded or unsanitary conditions

- Anyone who travels to an area where diphtheria is endemic

However, diphtheria is still common in developing countries where immunization rates are low. In areas where diphtheria vaccination is standard, the disease is mainly a threat to unvaccinated or inadequately vaccinated people who travel internationally or have contact with people from less-developed countries.

Diagnosis and Treatment of Diphtheria: There are definitive tests for diagnosing a case of diphtheria, so if symptoms and history cause a suspicion of the infection, it is relatively straightforward to confirm the diagnosis.

The current clinical case definition of diphtheria used by the United States’ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is based on both laboratory and clinical criteria

Doctors should be suspicious when they see the characteristic membrane, or patients have unexplained pharyngitis, swollen lymph nodes in the neck, and low-grade fever. Hoarseness, paralysis of the palate, or stridor (high-pitched breathing sound) is also clues.

Clinical specimens are taken from the nose and throat. All suspected cases and their close contacts are tested. If possible, swabs are also taken from under the pseudomembrane or removed from the membrane itself. The tests may not be readily available, and so doctors may need to rely on a specialist laboratory.

Diphtheria is fatal in 5 – 10% of cases, with a higher mortality rate in young children. Treatment involves administering diphtheria antitoxin to neutralize the effects of the toxin, as well as antibiotics to kill the bacteria.

The disease may remain manageable, but in more severe cases, lymph nodes in the neck may swell, and breathing and swallowing are more difficult. Diphtheria can also cause paralysis in the eye, neck, throat, or respiratory muscles. Patients with severe cases are put in a hospital intensive care unit and given a diphtheria antitoxin (consisting of antibodies isolated from the serum of horses that have been challenged with diphtheria toxin).

Treatment aimed at countering the bacterial effects has two components:

- An antitoxin. If doctors suspect diphtheria, the infected child or adult receives an antitoxin. The antitoxin, injected into a vein or muscle, neutralizes the diphtheria toxin already circulating in the body.

- Antibiotics. Diphtheria is also treated with antibiotics, such as penicillin or erythromycin. Antibiotics help kill bacteria in the body, clearing up infections. Antibiotics reduce to just a few days the length of time that a person with diphtheria is contagious.

Diphtheria is fatal in between 5% and 10% of cases. In children under five years and adults over 40 years, the fatality rate may be as much as 20%.

Diphtheria Vaccination: Diphtheria vaccine is a bacterial toxoid, ie. a toxin whose toxicity has been inactivated. The vaccine is normally given in combination with other vaccines as DTwP/DTaP vaccine or pentavalent vaccine. For adolescents and adults, the diphtheria toxoid is frequently combined with tetanus toxoid in lower concentration (Td vaccine).

WHO recommends a 3-dose primary vaccination series with diphtheria containing vaccine followed by 3 booster doses. The primary series should begin as early as 6-week of age with subsequent doses given with a minimum interval of 4 weeks between doses. The 3 booster doses should preferably be given during the second year of life (12-23 months), at 4-7 years and at 9-15 years of age. Ideally, there should be at least 4 years between booster doses.

Prevention of Diphtheria: Diphtheria is preventable with the use of antibiotics and vaccines. Quinvaxem is a widely administered pentavalent vaccine, which is a combination of five vaccines in one that protects babies from diphtheria, among other common childhood diseases. Diphtheria vaccine is usually combined at least with tetanus vaccine (Td) and often with pertussis (DTP, DTaP, TdaP) vaccines, as well.

In rare cases, a child might have an allergic reaction to the vaccine. This can result in seizures or hives, which will later go away.

Recovering from diphtheria requires lots of bed rest. Avoiding any physical exertion is particularly important if people’s heart has been affected. People may need to stay in bed for a few weeks or until they make a full recovery.

Once people recover from diphtheria, they will need a full course of diphtheria vaccine to prevent a recurrence. Having diphtheria doesn’t guarantee them lifetime immunity. People can get diphtheria more than once if they are not fully immunized against it.

Information Source: