The internet is fraught with dangers: sensitive data can be leaked, and malicious websites can grant hackers access to private computers. The Security & Privacy Research Unit at TU Wien, in collaboration with Ca’ Foscari University, has discovered a new critical security vulnerability that had previously gone unnoticed. Subdomains are common on large websites; for example, “sub.example.com” could be a subdomain of the website “example.com.” Certain tricks can be used to gain control of such subdomains. And if that happens, new security holes open up, putting people who simply want to use the website at risk (in this example, example.com).

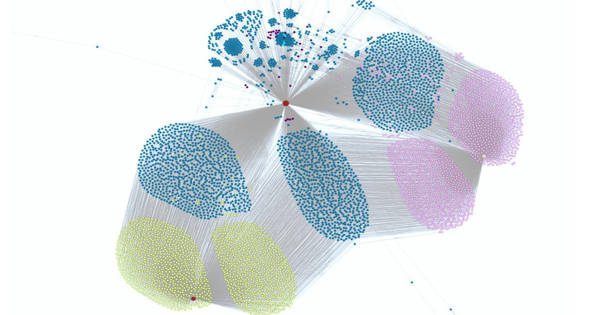

The research team investigated these vulnerabilities as well as the scope of the problem: 50,000 of the most important websites in the world were examined, and 1,520 vulnerable subdomains were discovered. The team was invited to the 30th USENIX Security Symposium, one of the most prestigious scientific conferences on cybersecurity. The findings have now been made public on the internet.

The research team studied these vulnerabilities and also analyzed how widespread the problem is: 50,000 of the world’s most important websites were examined, and 1,520 vulnerable subdomains were discovered.

Dangling records

“At first glance, the problem does not appear to be that serious,” says Marco Squarcina of TU Vienna’s Institute of Logic and Computation. “After all, you might believe that you can only gain access to a subdomain if the website administrator explicitly grants you permission, but this is incorrect.”

This is due to the fact that a subdomain frequently points to another website that is physically stored on a completely different server. Perhaps you own the website example.com and would like to add a blog. You don’t want to start from scratch, but rather use an existing blogging service from another website. As a result, a subdomain, such as blog.example.com, is linked to another website. “You won’t notice anything suspicious if you use the example.com page and click on the blog there,” says Marco Squarcina. “The browser’s address bar displays the correct subdomain blog.example.com, but the data now originates from a completely different server.”

But what if this link becomes invalid one day? Perhaps the blog is no longer required, or it has been relaunched elsewhere. The link from blog.example.com then points to an external page that no longer exists. In this case, “dangling records” refer to loose ends in the website’s network that are ideal points of attack.

“If such lingering records are not promptly removed, attackers can set up their own page there, which will then appear at sub.example.com,” Mauro Tempesta explains (also TU Wien).

This is a problem because websites apply different security rules to various parts of the internet. Even if they are controlled from outside, their own subdomains are typically considered “safe.” Cookies placed on users by the main website, for example, can be overwritten and potentially accessed from any subdomain: In the worst-case scenario, an intruder can impersonate another user and perform illegal actions on their behalf.

Alarmingly common problem

Marco Squarcina, Mauro Tempesta, Lorenzo Veronese, Matteo Maffei (TU Wien), and Stefano Calzavara (Ca’ Foscari) investigated the prevalence of this problem. “We looked at 50,000 of the most popular websites in the world and discovered 26 million subdomains,” says Marco Squarcina. “We discovered vulnerabilities on 887 of these sites, totaling 1,520 vulnerable subdomains.” Some of the most well-known websites, such as CNN.com and Harvard.edu, were among the vulnerable sites. University websites are more vulnerable because they typically have a large number of subdomains.

“We contacted everyone who was in charge of the vulnerable sites. Nonetheless, 6 months later, only 15% of these subsystems had been fixed “omains,” Marco Squarcina says. “In theory, these flaws should be simple to patch. We hope that by doing so, we can raise awareness about this security threat.”