A recent study has discovered that desert bighorn sheep in the Mojave National Preserve in California and the surrounding areas appear to be more resistant to a respiratory disease than previously believed. In 2013, the disease killed scores of animals and sickened many more.

Wildlife biologist Clint Epps of Oregon State University and his collaborators discovered that bighorn sheep populations in the Mojave have been exposed to one of the disease-causing bacteria for a longer period of time than previously assumed. However, scientists also discovered that since 2013, the total number of sick bighorn has decreased in the communities they studied.

Epps and his associates are cautiously enthusiastic about their findings, including Nicholas Shirkey, an environmental scientist with the California Department of Fish and Wildlife and the paper’s primary author.

“I wouldn’t let my guard down, but it has heartened me to see that the bighorn are hanging on,” said Epps, a professor in OSU’s College of Agricultural Sciences.

Scientists were perplexed by the 2013 respiratory disease outbreak and worried that it might have long-term effects on one of the only large mammals that can survive in this harsh desert habitat.

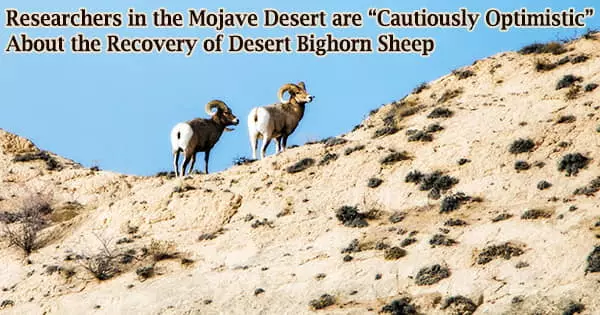

Weighting up to 250 pounds, desert bighorn sheep are distinguished by their huge, curled horns and their quick, agile ascent of rocky, steep terrain. Along with Mexico, they reside in California, Nevada, Utah, Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas.

Epps stated desert bighorn sheep are a species that unite people and that he started studying them in 1999.

“I’ve seen people from all walks of life people who are hunters, people who are desert aficionados, people who love biodiversity, people who just love these things for their iconic beauty all coming together around the conservation management of this species,” he said. “I have seen some really unusual partnerships.”

The findings in the paper show the importance of a sustained effort to collect data from these desert bighorn sheep. The data really help us understand what is happening with these populations so that we can make sure they survive.

Clint Epps

Shirkey added that the rare animals captivate people. “There’s fewer than 5,000 desert bighorn in the state of California,” he said. “There’s probably that many deer in parts of some counties. They live in small numbers in very difficult places and even just seeing one, you feel like you’ve gotten to have a real special experience.”

The study, which was written up in the Journal of Wildlife Diseases, reports the findings of an examination of antibodies to Mycoplasma ovipneumoniae, a bacterium linked to respiratory illness in bighorn sheep, in blood samples taken from sheep that had been seized.

The 2013 pathogen outbreak sparked interest in the desert bighorn sheep populations of the Mojave, inspiring the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, the National Park Service, Epps, and other partners to capture and release more animals in order to collect blood samples for health checks and population trends.

A little over 43,000 square miles, or 59% of it is in California, make up the Mojave Desert. The Mojave’s California portion is roughly the size of the state of West Virginia. Due to their enormous size, desert bighorn sheep can be found in various, though related, communities throughout the Mojave Desert in California. The California Department of Fish and Wildlife has captured sheep in 16 different mountain ranges.

In eight of those populations, they caught 70 desert bighorn sheep in 2013. The organism that causes the respiratory disorders, Mycoplasma ovipneumoniae, was recognized by antibodies in 60% of patients. Between 12% and 15% of the bighorn sheep that were captured in up to 12 of those areas over the course of the following four years carried the antibodies.

While most populations of bighorn have shown a decrease in the proportion of animals with antibodies since 2013, the researchers have found new areas where the virus has previously been present.

Additionally, the researchers examined blood samples taken from desert bighorn sheep in the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s. Only four of the 16 populations were represented in the samples they examined, which are preserved by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife.

They questioned whether the antibodies were to the same strain as that seen during the 2013 outbreak or a less virulent strain after discovering evidence that bighorn sheep in those populations had been exposed to the disease in all three of those decades.

In one instance, a group with exposure evidence in 1989–1990 seemed to have cleared the virus after a number of years, as subsequent testing failed to pick up exposure until the 2013 outbreak.

“The findings in the paper show the importance of a sustained effort to collect data from these desert bighorn sheep,” Epps said. “The data really help us understand what is happening with these populations so that we can make sure they survive.”

In addition to Epps and Shirkey, the authors of the paper are: Annette Roug (shared first author), Thomas Besser, Vernon C. Bleich, Neal Darby, Daniella Dekelaita, Nathan Galloway, Ben Gonzales, Debra Hughson, Lora Konde, Ryan Monello, Paige R. Prentice, Regina Vu, John Wehausen, Brandon Munk (shared senior author) and Jenny Powers (shared senior author.)

Funding for the research was provided by the California Department of Fish and Game Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration Project, Boone and Crockett Club, California Association of Professional Scientists, Foundation for North American Wild Sheep, National Rifle Association, Safari Club International, San Bernardino County Fish and Game Commission, Society for the Conservation of Bighorn Sheep, U.S. Department of Interior Bureau of Land Management, California Department of Fish and Wildlife, National Park Service, Oregon State University, Nevada Department of Wildlife, California Chapter of the Wild Sheep Foundation and the Desert Bighorn Council.