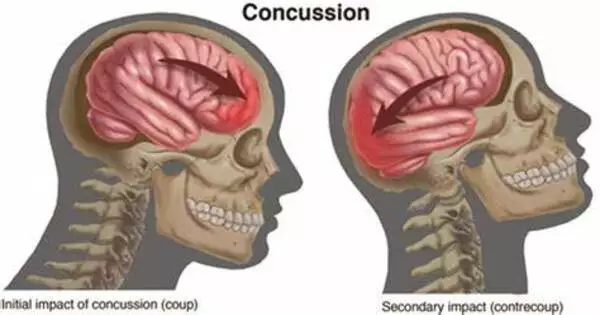

In order to encourage proper recovery and avert potential long-term complications, reducing subsequent injuries after a concussion is crucial. Researchers designed a study in which teenage athletes who sustained concussions were randomized to either standard of care (typically returning to play after clearing a set of standardized protocols that assess symptoms, cognition, and balance), or completing the same protocol and then working with an athletic trainer on a specific neuromuscular training intervention that includes guided strength exercises), in an effort to find ways to keep young athletes safer post-concussion.

As assistant professor of orthopedics at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, David Howell, PhD, understands the relationship between concussions and subsequent injury in athletes – namely, that after suffering a concussion, athletes at all levels are more likely to sustain another injury within the next year.

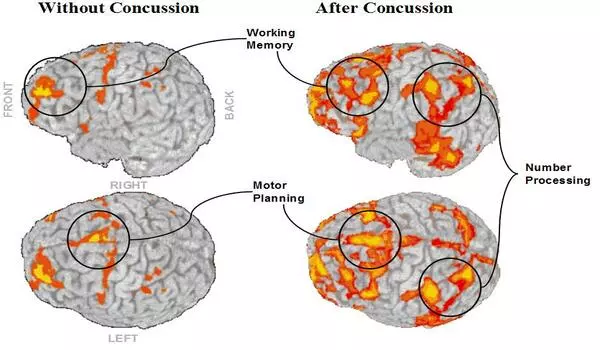

“Any athlete may experience an injury such as an ankle sprain or an ACL rupture – that’s just a part of sports,” says Howell, the head of the sports medicine research group at Children’s Hospital Colorado. But those who have recently suffered concussions are often more susceptible to them. We continue to observe neuromuscular motor control deficits even after symptoms have subsided and an athlete has been given the all-clear to resume sports, especially when they are combined with a cognitive task. These unresolved deficits could put them at risk for further harm.

It’s similar to injury risk reduction programs that are used more in population-level studies. You take an entire high school soccer team and run them through these neuromuscular training programs over a season, then compare them to a team that didn’t do the program.

David Howell

Enter the intervention

Howell and the investigative team designed a study in which teenage athletes who sustained concussions were randomized to receive standard of care, which usually involves returning to play after passing a series of standardized protocols that assess symptoms, cognition, and balance, or to receive standard of care and then work with an athletic trainer on a particular neuromuscular training intervention that includes exercises like balancing, coordination, and strength training.

“It’s similar to injury risk reduction programs that are used more in population-level studies,” Howell says. “You take an entire high school soccer team and run them through these neuromuscular training programs over a season, then compare them to a team that didn’t do the program. Those studies showed that if you have a team go through this, it can reduce the risk of ACL tears, for example, pretty significantly.”

Howell enrolled 27 post-concussion youth athletes in the study, most of whom were patients in the Sports Medicine Center at Children’s Hospital Colorado. The athletes who were randomized to the intervention worked with an athletic trainer two times a week for eight weeks; researchers followed them for a full year following their concussion.

“We asked them every month over the following year, ‘Did you play sports? How many games did you have? How many practices do you have? How many hours did you participate’ – plus, ‘Did you get injured or not?'” Howell says. “What we found is that the people who went through the intervention had about a three-and-a-half times reduced injury risk compared to the ones that did not go through the intervention over that next year.”

Changing the rules on return-to-play

Howell anticipates that the findings of his research will eventually alter the process of allowing athletes to return to play, refocusing attention away from self-reported symptoms and computerized tests and toward a standardized intervention that can help prevent further injuries.

Even in cases where they don’t have access to a qualified clinician, such as an athletic trainer or physical therapist, he and his research team are developing an app to assist athletes through a self-guided training program.

“When you think about sports, it’s not just looking at a computer screen, doing a reaction time test, or performing a single balance test,” he claims. It involves the integration of numerous systems. Imagine passing a soccer ball to a teammate who is standing across the way while you are standing where you are. But what does your foot’s angle represent? Where are the adversaries? All of those things require numerous quick-reaction cognitive and fine motor skills.

“We think that can have an effect,” he says, “if this can help with at least some of those elements that can contribute to safety.” The preliminary study’s findings were very positive, and I’m eager to see where things go from here.