According to a recent survey conducted in the United States, prejudice against East Asian and Hispanic coworkers may have increased as a result of the COVID-19 outbreak. On April 13 (2022), Columbia University in New York and Northwestern University in Chicago researchers Neeraj Kaushal, Yao Lu, and Xiaoning Huang published their findings in the open-access journal PLOS ONE.

Discrimination and hate crimes against minorities have escalated since the COVID-19 pandemic started, especially against Chinese Americans. The majority of reported incidents involved strangers and happened in public.

The possible effects of the pandemic on workplace views toward ethno-racial minorities, however, have not been fully understood because workplace prejudice is less likely to be reported. 3,837 working-age American individuals were surveyed in August 2020, during the beginning of the pandemic, and their responses were examined by Kaushal and colleagues.

Each respondent received one of two survey versions; the first began with a brief overview of the pandemic and then asked about how COVID-19 had affected them personally and, in the case of a fictitious workplace scenario, their preference for working with a fictitious coworker from a particular ethno-racial group.

The hypothetical colleague was the first individual who was mentioned in the second version’s question concerning COVID-19’s personal effects.

Our findings highlight a dimension of prejudice, intensified during the pandemic, which has been largely underreported and missing from the current discourse. Workplace discrimination can alienate minorities and sow seeds of distrust that can have long-term impacts spilling across generations.

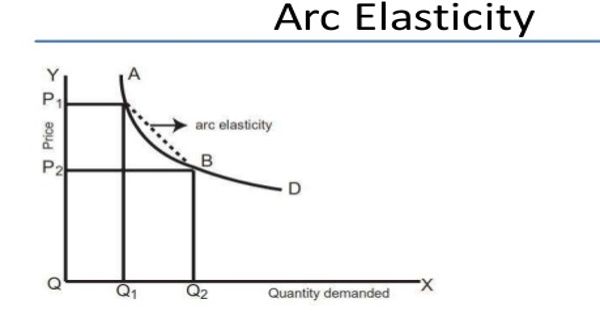

According to a statistical analysis of the survey responses, participants’ acceptance of hypothetical East Asian coworkers and supervisors as well as acceptance of hypothetical Hispanic coworkers, supervisors, and staff members was reduced after being primed with information about the pandemic and survey questions about it.

Participants from counties with higher incidences of COVID-19 and lower East Asian population densities, as well as those who had experienced job loss due to COVID-19, displayed greater prejudice in their comments. There was no proof of prejudice against fictitious South Asian, Black, or White coworkers.

These results raise the likelihood that the pandemic exacerbated Americans’ health and financial anxieties, aggravating bias against minority groups in the workplace.

According to earlier studies, such beliefs enhance the chance of discriminatory actions, which can negatively affect minorities’ productivity and economic possibilities, their mental and physical health, and their social integration over the course of several generations.

The authors add: “Our findings highlight a dimension of prejudice, intensified during the pandemic, which has been largely underreported and missing from the current discourse. Workplace discrimination can alienate minorities and sow seeds of distrust that can have long-term impacts spilling across generations.”