Men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer should be treated predominantly with second-generation hormone therapies, which provide better treatment outcomes and a longer life expectancy than chemotherapy. However, the effect is determined on the mutations present in the patient’s cancer. The findings of the ProBio study, led by experts at Sweden’s Karolinska Institutet, support this assertion. The findings were published in Nature Medicine.

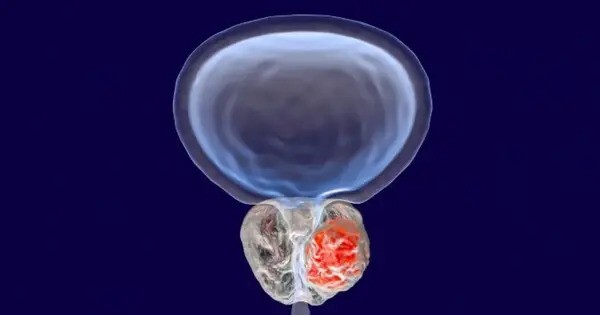

Every year in Sweden, approximately 2,500 men are diagnosed with metastatic prostate cancer. Initially, all are treated with testosterone blocking to prevent testosterone from activating the androgen receptor, which is the gene that primarily stimulates cancer cell proliferation. Over time, cancer cells build resistance and become “castration-resistant.”

This necessitates the use of novel medications, typically chemotherapy or second-generation hormone therapies (abiraterone/enzalutamide), which suppress the androgen receptor. These are known as Androgen Receptor Pathway Inhibitors, or ARPi. Although these medications have been on the market for more than a decade, there has been no direct comparison from a randomised trial until now.

Our study shows that it is possible to ensure that each patient receives the best treatment given the genetic profile of the tumour. Everyone talks about precision medicine, but studies like ProBio are needed to understand how biomarkers can help patients.

Henrik Grönberg

“For the first time, we have compared these treatments with each other and also analysed the DNA of the cancer cells to find out which drug that works best for different individuals,” says Johan Lindberg, senior researcher at the Department of Medical Epidemiology and Biostatistics (MEB), Karolinska Institutet.

The bloodstream contains so-called cell-free DNA from cells that have died, something that happens all the time in healthy individuals and is perfectly normal. In patients with cancer, a fraction of the cell-free DNA originates from the cancer cells and is called circulating tumour DNA (ctDNA). By analysing ctDNA, it is possible to see what changes, or mutations, are present in a person’s tumour. The ProBio study aims to use knowledge of the tumour’s genetic signature to provide the best treatment. The idea is to be able to identify patients whose tumours are particularly sensitive or resistant to certain treatments through ongoing analyses.

“It creates a self-learning system to continuously improve treatment for men with metastatic prostate cancer,” says Martin Eklund, Professor of Epidemiology at the same department. “We are also gathering knowledge about which regions of the genome are important in prostate cancer.”

The current sub-study included 193 patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. They were randomly chosen to receive either chemotherapy or ARPi, which was compared to a control group where the doctor decided on the best treatment. The ARPi group responded the longest to treatment (a median of 11.1 months compared with 6.9 for chemotherapy and 7.4 for the control group). Survival for the ARPi group was also significantly longer — a median of 38.7 months compared with 21.7 months and 21.8 months respectively.

The effectiveness of ARPi varied depending on the patient’s genetic profile. For example, there was no significant difference between the treatments in the short term in patients whose tumours had mutations in the p53 gene, which occurs in around 45 per cent of men with metastatic prostate cancer. However, data from the study suggest that this group may also have better survival if they receive ARPi rather than chemotherapy.

“Our study shows that it is possible to ensure that each patient receives the best treatment given the genetic profile of the tumour,” says Henrik Grönberg, Professor of Cancer Epidemiology, MEB, Karolinska Institutet. “Everyone talks about precision medicine, but studies like ProBio are needed to understand how biomarkers can help patients.”

ProBio includes researchers and doctors from 31 hospitals, ten of which are in Sweden and the remainder in Belgium, Norway, and Switzerland. The study is supported by ALF, the Swedish Cancer Society, the Swedish Research Council, and the pharmaceutical companies AstraZeneca and Janssen.

Several of the authors are stockholders, board members, or have disclosed that they have received compensation from numerous pharmaceutical companies. Johan Lindberg is recognized as an inventor on a Swedish patent application for a method employed in the study, which will be made freely available under the GPL 3.0 license. The scientific article has a comprehensive list of conflicts of interest.