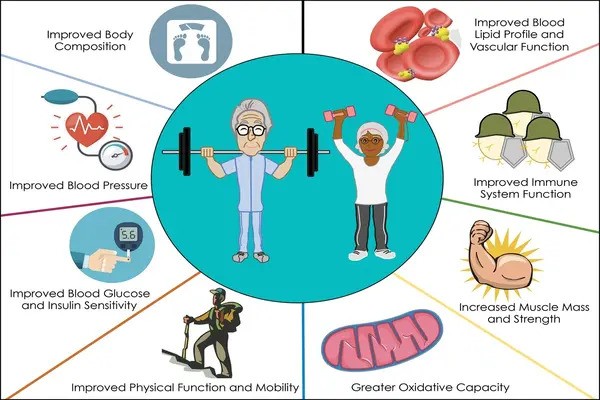

Over a ten-year period, biobank participants who met prescribed levels of physical activity had a 23% decreased risk of cardiovascular disease, with the protective effects being particularly stronger among those with depression.

According to new research, physical activity reduces the risk of cardiovascular disease by lowering stress-related signals in the brain. The study, led by investigators at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), a founding member of the Mass General Brigham healthcare system, and published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, found that people with stress-related conditions such as depression benefited the most from physical activity.

Ahmed Tawakol, MD, an investigator and cardiologist in the Cardiovascular Imaging Research Center at Massachusetts General Hospital, and his colleagues examined medical records and other data from 50,359 participants in the Mass General Brigham Biobank who completed a physical activity survey to determine the mechanisms underlying the psychological and cardiovascular disease benefits of physical activity.

Prospective studies are needed to identify potential mediators and to prove causality. In the meantime, clinicians could convey to patients that physical activity may have important brain effects, which may impart greater cardiovascular benefits among individuals with stress-related syndromes such as depression.

Ahmed Tawakol

A subset of 774 participants received brain imaging examinations as well as stress-related brain activity assessments. After a median follow-up of ten years, 12.9% of individuals had cardiovascular disease. Participants who met physical activity recommendations had a 23% decreased risk of getting cardiovascular disease than those who did not achieve them.

Individuals with higher levels of physical activity also tended to have lower stress-related brain activity. Notably, reductions in stress-associated brain activity were driven by gains in function in the prefrontal cortex, a part of the brain involved in executive function (i.e., decision making, impulse control) and is known to restrain stress centers of the brain. Analyses accounted for other lifestyle variables and risk factors for coronary disease.

Furthermore, reductions in stress-related brain signals contributed to physical activity’s cardiovascular effect. As an extension of this discovery, the researchers discovered in a cohort of 50,359 participants that the cardiovascular effect of exercise was much greater among participants who would be anticipated to have higher stress-related brain activity, such as those with a history of depression.

“Physical activity was roughly twice as effective in lowering cardiovascular disease risk among people suffering from depression.” Tawakol, the study’s principal author, believes that effects on the brain’s stress-related activity could explain this unexpected result.

“Prospective studies are needed to identify potential mediators and to prove causality. In the meantime, clinicians could convey to patients that physical activity may have important brain effects, which may impart greater cardiovascular benefits among individuals with stress-related syndromes such as depression.”