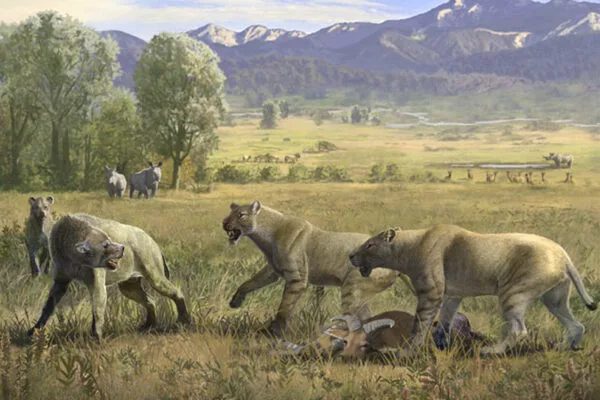

Palaeontologists’ discovery of two new species of sabertooth cats can provide vital insights into the diversity and evolution of these intriguing beasts. Smilodon, or sabertooth cats, were extinct predatory felids with long, curved canine teeth that were well-suited for killing huge herbivores during the Pleistocene period.

Sabertooth cats are a diversified species of long-toothed carnivores that roamed Africa circa 6-7 million years ago, around the time that hominins (modern humans included) began to evolve. Researchers report two new sabertooth species and the first family tree of the region’s ancient sabertooths in the journal iScience on July 20 after investigating one of the world’s largest Pliocene fossil collections in Langebaanweg, north of Cape Town in South Africa. Their findings show that the distribution of sabertooths in ancient Africa may have been different than previously thought, and the study adds to our understanding of Africa’s paleoenvironment.

“The known material of sabertooths from Langebaanweg was relatively poor, and the importance of these sabertoothed cats has not been properly recognized,” says senior author Alberto Valenciano, a paleontologist at Complutense University. “Our phylogenetic analysis is the first one to take Langebaanweg species into consideration.”

The known material of sabertooths from Langebaanweg was relatively poor, and the importance of these sabertoothed cats has not been properly recognized. Our phylogenetic analysis is the first one to take Langebaanweg species into consideration.

Alberto Valenciano

The study described four different species. Dinofelis werdelini and Lokotunjailurus chimsamyae were previously unknown species. Dinofelis sabertooths are found all over the world, with fossils discovered in Africa, China, Europe, and North America. Based on a previous study, the researchers expected to discover a new Dinofelis species in Langebaanweg. However, prior to this study, Lokotunjailurus had only been seen in Kenya and Chad. This shows that they were spread throughout Africa between 5-7 million years ago.

Valenciano worked as a postdoctoral scholar at South Africa’s Iziko Museums, which possesses all of the sabertooth fossils studied in this study. The final project was put together by a group of colleagues from China, South Africa, and Spain. To create a family tree, the researchers classified each sabertooth species’ physical characteristics, such as tooth presence or absence, jaw and skull shape, and tooth structure, and coded this information into a matrix that could determine how closely related each sabertooth was to its evolutionary cousins.

The demographic makeup of Langebaanweg sabertooths (Machairodontini, Metailurini, and Feline) as a result reflects the Pliocene epoch’s growing global temperatures and climatic changes. For example, the existence of Machairodontini cats, which are larger and better adapted to running at high speeds, implies that wide grassland conditions existed at Langebaanweg.

The presence of Metailurini cats, on the other hand, shows that there were also more covered settings, such as woods. While the discovery of both Metailurine and Machairodonti species suggests that Langebaanweg contained a mix of forest and grassland 5.2 million years ago, the high proportion of Machairodonti species found in comparison to other fossil localities in Eurasia and Africa confirms that southern Africa was transitioning towards more open grasslands at the time.

“The continuous aridification throughout the Mio-Pliocene, with the spread of open environments, could be an important trigger on the bipedalism of hominids,” the authors write. “The sabertooth guild in Langebaanweg and its environmental and paleobiogeographic implications provide background for future discussion on hominid origination and evolution.”

Interestingly, the researchers also note that the composition of sabertooths in Langebaanweg closely mirrors that of Yuanmou, China. Yuanmou’s Longchuansmilus sabertooths might even have a close evolutionary relationship with Africa’s Lokotunjailurus species.

“This suggests that the ancient environment of the two regions was similar or that there was a potential migration route between the Langebaanweg and Yuanmou,” explains first author and Peking University palaeontologist Qigao Jiangzuo.

More fossil material could assist palaeontologists figure out how these two sites are linked. “The two new sabertooths are just two of the many unpublished fossils from Langebaanweg housed at Iziko in the Cenozoic Collections,” explains Romala Govender, curator, and palaeontologist at South Africa’s Iziko Museums. “This highlights the need for new and detailed studies of the Langebaanweg fauna.”