An examination of ancient and modern DNA reveals that ancient Africans looking for mates swapped long-distance travel for localized relationships some 20,000 years ago. Our new study, led by an interdisciplinary team of 44 experts from 12 nations, contributes to answering these issues. We almost quadrupled the age of sequenced aDNA from Sub-Saharan Africa by sequencing and analyzing ancient DNA (aDNA) from people who lived as long as 18,000 years ago. And this genetic information helps anthropologists like us learn more about how modern humans moved and interbred in Africa a long time ago.

This transformation occurred after trips throughout much of Africa to find breeding mates became the norm at least 50,000 years ago, according to the same analysis. These new findings, aided by multiple cases of the earliest human DNA extracted from Africa to date, provide the first genetic support for a previously suspected change in mating patterns around that period.

These newly discovered long-distance movements of ancient human groups help to explain archaeological discoveries of common types of stone and bone toolmaking and other cultural behaviors that began to appear across much of Africa around 50,000 years ago, according to evolutionary geneticist Mark Lipson of Harvard Medical School and colleagues in Nature.

As the African tropics came out of the last ice age, the landscape became full of many small groups of people with diverse local cultural traditions. We almost quadrupled the age of sequenced aDNA from Sub-Saharan Africa by sequencing and analyzing ancient DNA (aDNA) from people who lived as long as 18,000 years ago.

Jessica Thompson

Beginning around that time, inherited sets of gene mutations were increasingly similar in ancient individuals located in Sub-Saharan Africa’s central, eastern, and southern areas, according to the researchers. This shows that this area was a genetic melting pot where hunter-gatherers moved across the three regions, mating with one another along the way.

Comparisons of ancient human DNA to that of modern hunter-gatherers and herders in the same three locations of Africa show that individuals stopped going outside their home regions to locate mating partners some 20,000 years ago, according to the researchers. People may have stayed closer to home at least partly because the last ice age peaked around that time, reducing the number of areas harboring enough edible plants, animals and other resources needed to survive, says Yale University bioarchaeologist and study coauthor Jessica Thompson.

“As the African tropics came out of the last ice age, the landscape became full of many small groups of people with diverse local cultural traditions,” Thompson says. Culturally distinct groups tended to seek mates from neighboring groups with whom they had more in common than migrants from distant regions, she suspects.

Today’s African hunter-gatherers continue to engage local cultural customs, talk in geographically diverse tongues, and attract mates from neighboring groups. Migrations of West African farmers to eastern and southern Africa that began some 2,000 years ago have virtually erased historic ancestral patterns in the DNA of modern Africans. As a result, ancient DNA is critical for resurrecting those long-lost patterns.

In the current study, scientists recovered ancient DNA from the bones of six previously uncovered individuals from eastern and south-central Africa. Estimates of when these people lived range from 18,000 to 5,000 years ago. These new genetic data were compared to previously published DNA evidence for 28 African hunter-gatherers dating back as far as 8,000 years. The researchers were able to retrieve additional DNA for 15 of those individuals.

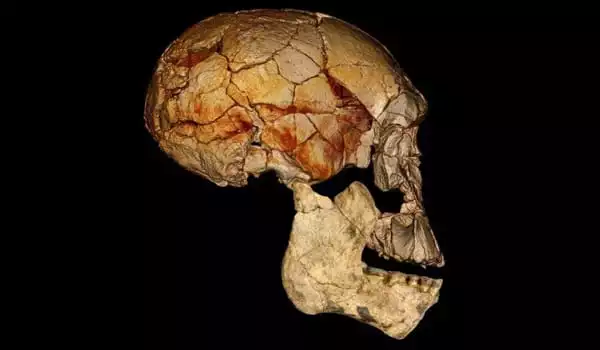

A big boost to the new investigation came from the inclusion of several examples of the oldest known human DNA from Africa. Even older examples of DNA from Homo sapiens and closely related populations, including Neandertals from around 430,000 years ago, have been found in Europe and Asia where cold conditions preserve genetic material better than the African tropics do. Only H. sapiens is known to have inhabited Africa during the Stone Age stretch covered in the new study.

Calculations of genetic variation in three contemporary African groups — San hunter-gatherers from southern Africa, Mbuti hunter-gatherers from central Africa, and Dinka herders and farmers from northeastern Africa — were used to estimate ancestral patterns reflected in each ancient DNA sample.

According to evolutionary geneticist Carina Schlebusch of the University of Uppsala in Sweden, who did not participate in the new study, Lipson and colleagues’ findings fit with previous ancient and modern African DNA studies suggesting that mating among widespread human groups began 200,000 years ago or more.