A new Cornell University study shows that avian influenza spread from birds to dairy cattle in numerous states has now resulted in mammal-to-mammal transmission — between cows and cows to cats and a raccoon.

“This is one of the first times that we are seeing evidence of efficient and sustained mammalian-to-mammalian transmission of highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1,” said Diego Diel, associate professor of virology and director of the Virology Laboratory at the Animal Health Diagnostic Center in the College of Veterinary Medicine.

Diel is co-corresponding author of the study, “Spillover of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza H5N1 Virus to Dairy Cattle” published in Nature.

Whole genome sequencing of the virus did not reveal any mutations in the virus that would lead to enhanced transmissibility of H5N1 in humans, although the data clearly shows mammal-to-mammal transmission, which is concerning as the virus may adapt in mammals, Diel said.

The concern is that potential mutations could arise that could lead adaptation to mammals, spillover into humans and potential efficient transmission in humans in the future.

Diego Diel

So far, 11 human cases have been reported in the U.S., with the first dating back to April 2022, each with mild symptoms: four were linked to cattle farms and seven have been linked to poultry farms, including an outbreak of four cases reported in the last few weeks in Colorado. These recent patients fell ill with the same strain identified in the study as circulating in dairy cows, leading the researchers to suspect that the virus likely originated from dairy farms in the same county.

While the virus can infect and multiply in humans, the efficacy of these infections is poor. “The concern is that potential mutations could arise that could lead adaptation to mammals, spillover into humans and potential efficient transmission in humans in the future,” Diel told reporters.

According to Diel, it is vital to continue monitoring the virus in impacted animals as well as any potentially infected humans. The United States Department of Agriculture has financed H5N1 testing programs at no cost to producers. Early testing, heightened biosecurity, and quarantines in the event of positive results would be required, according to Diel, to prevent the virus from spreading further.

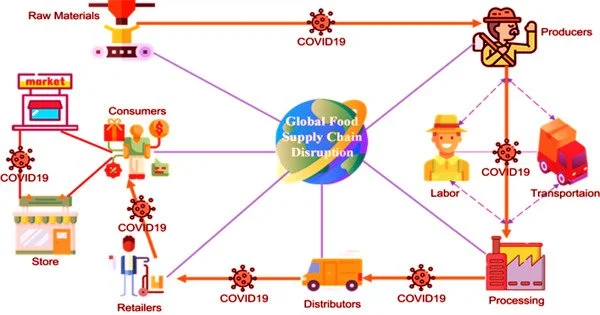

Infections from H5N1 were first detected in January 2022, and have resulted in the deaths of more than 100 million domestic birds and thousands of wild birds in the U.S. The Cornell AHDC’s and Texas A&M Veterinary Medical Diagnostic Laboratory scientists were among the first to report detection of the virus to dairy cattle herds. The cows were likely infected by wild birds, leading to symptoms of reduced appetite, changes in fecal matter consistency, respiratory distress and abnormal milk with pronounced decrease in milk production.

The study shows a high tropism of the virus (capability to infect particular cells) for the mammary gland and high infectious viral loads shed in milk from affected animals.

Using whole genome sequencing of described viral strains, modeling, and epidemiological data, the researchers identified incidences of cow-to-cow transmission when sick cows from Texas were relocated to a farm with healthy cows in Ohio. Sequencing also revealed that the virus infected cats, a raccoon, and wild birds found dead on afflicted fields. The cats and raccoon most likely developed ill after consuming raw milk from contaminated cows. Though it is unclear how the wild birds became sick, the researchers believe it was caused by environmental pollution or aerosols released during milking or cleaning of the milking parlors.