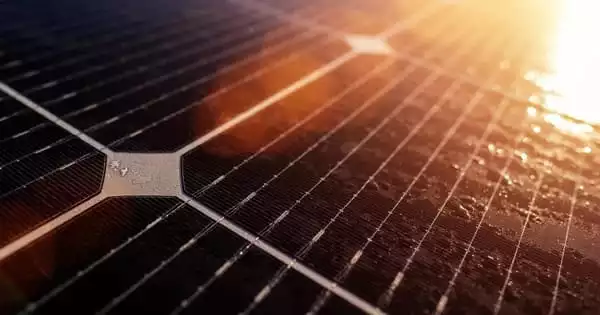

More and more firms are investing in commercial solar panels all over the world. This is due to a number of factors. For starters, solar panel efficiency has increased dramatically in recent years. With governments establishing aggressive net-zero targets, there is also rising pressure on businesses to employ renewable energy solutions to decrease their carbon impact.

Many firms spend a lot of money on commercial solar panels. However, some people aren’t doing enough to keep their solar panels efficient over their lifetime. As a result, their panels don’t produce as much electricity as they should, which costs the company money.

A research team created a highly effective tandem solar cell built of perovskite and organic absorbers that may be manufactured at a cheaper cost than standard silicon solar cells. This technology’s advancement is projected to make solar energy even more sustainable.

A German research team has developed a tandem solar cell that reaches 24 per cent efficiency — measured according to the fraction of photons converted into electricity (i.e. electrons). This sets a new world record as the highest efficiency achieved so far with this combination of organic and perovskite-based absorbers. The solar cell was developed by Professor Dr Thomas Riedl’s group at the University of Wuppertal together with researchers from the Institute of Physical Chemistry at the University of Cologne and other project partners from the Universities of Potsdam and Tübingen as well as the Helmholtz-Zentrum Berlin and the Max-Planck-Institut für Eisenforschng in Düsseldorf.

To reach such high efficiency, the losses at the interfaces between the materials within the solar cells have to be minimized. To address this issue, the Wuppertal group created a so-called connector that electronically and optically connects the organic and perovskite sub-cells.

Dr Selina Olthof

The results have been published in Nature under the title “Perovskite/organic tandem solar cells with indium oxide interconnect.”

Conventional solar cell technologies are mostly based on the semiconductor silicon and are now considered to be “as good as it gets.” Significant advances in their efficiency — that is, more watts of electrical output per watt of solar radiation gathered — are unlikely. That makes it even more critical to develop innovative solar technologies that can make a significant contribution to the energy transition. In this experiment, two different absorber materials were mixed. Organic semiconductors were used in this case, which are carbon-based compounds that may conduct electricity under certain conditions.

These were paired with a perovskite, based on a lead-halogen compound, with excellent semiconducting properties. Both of these technologies require significantly less material and energy for their production compared to conventional silicon cells, making it possible to make solar cells even more sustainable.

Because sunlight has distinct spectral components, or colors, efficient solar cells must convert as much of this sunlight as possible into energy. This is possible with so-called tandem cells, which combine different semiconductor materials in the solar cell, each of which absorbs a different portion of the light spectrum. Organic semiconductors were used in the current work for the ultraviolet and visible portions of the light, while perovskite can efficiently absorb in the near-infrared. Similar material combinations have been investigated in the past, but the research team has now greatly improved their performance.

At the outset of the research, the best perovskite/organic tandem cells in the world had an efficiency of roughly 20%. The Cologne researchers, along with the other project partners, were able to enhance this value to an astounding 24 percent under the supervision of the University of Wuppertal. ‘To reach such high efficiency, the losses at the interfaces between the materials within the solar cells have to be minimized,’ stated Dr Selina Olthof of the Institute of Physical Chemistry at the University of Cologne. ‘To address this issue, the Wuppertal group created a so-called connector that electronically and optically connects the organic and perovskite sub-cells.’

To keep losses as low as possible, a thin layer of indium oxide was integrated into the solar cell as an interconnect with a thickness of only 1.5 nanometres. The Cologne researchers were instrumental in examining the energy and electrical properties of the interfaces and connections to detect loss mechanisms and further optimize the components. The Wuppertal group’s simulations revealed that tandem cells with an efficiency of more than 30% might be obtained in the future with this approach.