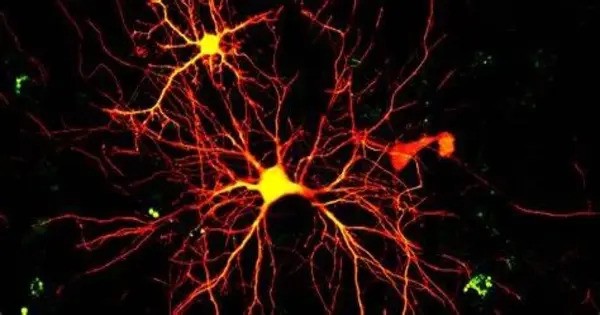

New information suggests that the cells responsible for communication in the brain may be shaped differently in children with autism. Researchers at the Del Monte Institute for Neuroscience at the University of Rochester discovered that neuron density varies in certain areas of the brain in children with autism compared to the general population.

“We’ve spent many years describing the larger characteristics of brain regions, such as thickness, volume, and curvature,” said Zachary Christensen, an MD/PhD candidate at the University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry and first author of the research published today in Autism Research. “However, newer techniques in the field of neuroimaging for characterizing cells using MRI, unveil new levels of complexity throughout development.”

People with a diagnosis of autism often have other things they have to deal with, such as anxiety, depression, and ADHD. But these findings mean we now have a new set of measurements that have shown unique promise in characterizing individuals with autism.

Zachary Christensen

Imaging provides new insight into brain development

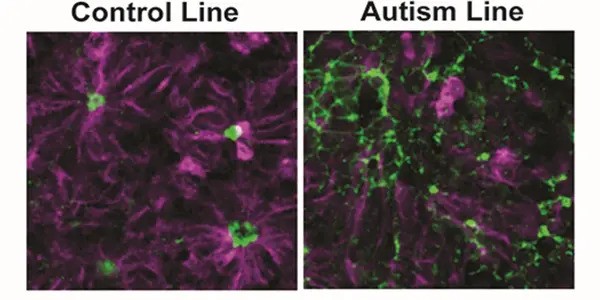

More than 11,000 children aged 9 to 11 were studied using brain imaging data. They compared the imaging of 142 children with autism to the general population and discovered reduced neuron density in cerebral cortical regions. Memory, learning, reasoning, and problem-solving are some of the tasks that these brain areas are responsible for. In contrast, the researchers discovered increased cell density in other brain regions, including the amygdala (an area responsible for emotions).

In addition to comparing the scans of children with autism to those of children with no neurodevelopmental diagnosis, scientists also compared the children with autism to a large group of children diagnosed with common psychiatric disorders such as ADHD and anxiety. The results were the same, suggesting that these differences are specific to Autism.

“People with a diagnosis of autism often have other things they have to deal with, such as anxiety, depression, and ADHD. But these findings mean we now have a new set of measurements that have shown unique promise in characterizing individuals with autism,” Christensen said. “If characterizing unique deviations in neuron structure in those with autism can be done reliably and with relative ease, that opens a lot of opportunities to characterize how autism develops, and these measures may be used to identify individuals with autism that could benefit from more specific therapeutic interventions.”

Technology leverages what we know about the innerworkings of the brain and autism

Technology has improved the precision and detail that investigators can currently perceive in neural structure. Previously, researchers could only identify structural alterations in neuronal populations after death. The imaging data used in this investigation were obtained from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study database.

It is the most extensive long-term research of brain development and child health. The University of Rochester is one of 21 nationwide locations gathering data for this study, which began in 2015 and has transformed our understanding of adolescent brain health and development.

“We are at the beginning of understanding the true impact that the extraordinary data collected by the ABCD Study will have on the health of our children,” said John Foxe, PhD, senior author of the study, director of the Del Monte Institute for Neuroscience and the Golisano Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Institute. “It is truly transforming what we know about brain development as we follow this group of children from childhood into early adulthood.”