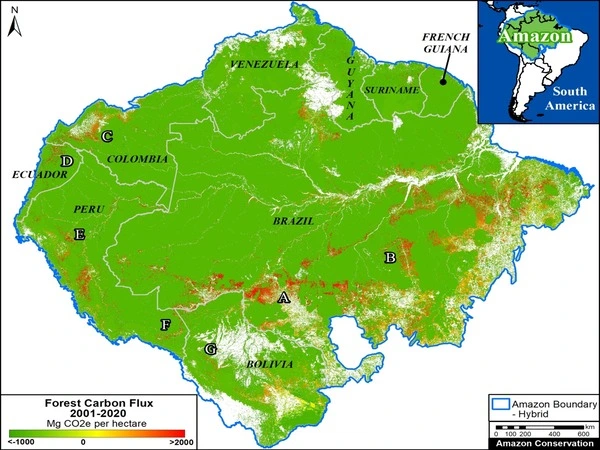

Climate change is likely to have a significant impact on the Amazon rainforest, including increased risk of drought and fires, which can lead to deforestation and loss of trees. As temperatures rise and precipitation patterns change, some tree species may become less able to survive in the Amazon, while others may become more prevalent. Additionally, as the forest is fragmented by human activities, such as logging and agriculture, it becomes more vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. Overall, the health and resilience of the Amazon rainforest is closely tied to the global climate, and efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and protect this vital ecosystem are crucial to its survival.

Tropical forests are critical for absorbing CO2 from the atmosphere. They are, however, vulnerable to severe storms, which can result in “windthrow,” or the uprooting or breaking of trees. As these downed trees decompose, they have the potential to transform a forest from a carbon sink to a carbon source.

According to a new study, more extreme thunderstorms caused by climate change will likely result in an increase in the number of large windthrow events in the Amazon rainforest. This is one of the few ways researchers have established a link between storm conditions in the atmosphere and forest mortality on land, filling a significant gap in models.

“Building this link between atmospheric dynamics and damage at the surface is very important across the board,” said Jeff Chambers, a senior faculty scientist at the Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab), and director of the Next Generation Ecosystem Experiments (NGEE)-Tropics project, which performed the research. “It’s not just for the tropics. It’s high-latitude, low-latitude, temperate-latitude, here in the U.S.”

Climate change has a lot of impact on Amazon forests, but so far, a large fraction of the research focus has been on drought and fire. We hope our research brings more attention to extreme storms and improves our models to work under a changing environment from climate change.

Jeff Chambers

Researchers found that the Amazon will likely experience 43% more large blowdown events (of 25,000 square meters or more) by the end of the century. The area of the Amazon likely to see extreme storms that trigger large windthrows will also increase by about 50%. The study was published in the journal Nature Communications.

“We want to know what these extreme storms and windthrows mean for the carbon budget and carbon dynamics, as well as for carbon sinks in the forests,” Chambers explained. While fallen trees slowly release carbon as they decompose, the open forest becomes home to new plants that absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. “It’s a complicated system, and we’re still working on many pieces of the puzzle. To get a more quantitative answer, we need to build out the land-atmosphere links in Earth system models.”

Researchers compared a map of over 1,000 large windthrows with atmospheric data to discover the link between air and land. They discovered that a metric known as CAPE, or “convective available potential energy,” was an accurate predictor of major blowdowns. CAPE is a measure of the amount of energy available to move parcels of air vertically, and a high CAPE value frequently results in thunderstorms. Extreme storms can bring strong vertical winds, heavy rains or hail, and lightning, all of which interact with trees from the canopy to the soil.

“Storms account for over half of the forest mortality in the Amazon,” said Yanlei Feng, first author on the paper. “Climate change has a lot of impact on Amazon forests, but so far, a large fraction of the research focus has been on drought and fire. We hope our research brings more attention to extreme storms and improves our models to work under a changing environment from climate change.”

While this study focused on a future with high carbon emissions (SSP-585), scientists could use projected CAPE data to investigate windthrow impacts in various emissions scenarios. The new forest-storm relationship is now being integrated into Earth system models by researchers. Better models will allow scientists to investigate how forests will respond to a warmer future, and whether they will continue to remove carbon from the atmosphere or become a contributor.

“This was a very impactful climate change study for me,” said Feng, who completed the study as a graduate student researcher in Berkeley Lab’s NGEE-Tropics project. She is now researching carbon capture and storage at Stanford University’s Carnegie Institution for Science. “I’m concerned about the projected increase in forest disturbances in our study, and I’m hoping that I can contribute to limiting climate change. As a result, I’m now working on climate change solutions.”