The earth was like an oven. The afternoon sun blazed with such energy that even the thermometer hanging in the excise officer’s room lost its head: it ran up to 112.5 and stopped there, irresolute. The inhabitants streamed with perspiration like overdriven horses, and were too lazy to mop their faces.

Two of the inhabitants were walking along the market-place in front of the closely shuttered houses. One was Potcheshihin, the local treasury clerk, and the other was Optimov, the agent, for many years a correspondent of the Son of the Fatherland newspaper. They walked in silence, speechless from the heat. Optimov felt tempted to find fault with the local authorities for the dust and disorder of the market-place, but, aware of the peace-loving disposition and moderate views of his companion, he said nothing.

In the middle of the market-place Potcheshihin suddenly halted and began gazing into the sky.

“What are you looking at?”

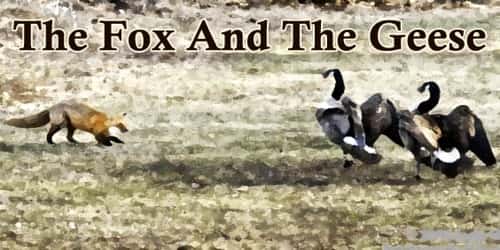

“Those starlings that flew up. I wonder where they have settled. Clouds and clouds of them. . . . If one were to go and take a shot at them, and if one were to pick them up . . . and if . . . They have settled in the Father Prebendary’s garden!”

“Oh no! They are not in the Father Prebendary’s, they are in the Father Deacon’s. If you did have a shot at them from here you wouldn’t kill anything. Fine shot won’t carry so far; it loses its force. And why should you kill them, anyway? They’re birds destructive of the fruit, that’s true; still, they’re fowls of the air, works of the Lord. The starling sings, you know. . . . And what does it sing, pray? A song of praise. . . . ‘All ye fowls of the air, praise ye the Lord.’ No. I do believe they have settled in the Father Prebendary’s garden.”

Three old pilgrim women, wearing bark shoes and carrying wallets, passed noiselessly by the speakers. Looking enquiringly at the gentlemen who were for some unknown reason staring at the Father Prebendary’s house, they slackened their pace, and when they were a few yards off stopped, glanced at the friends once more, and then fell to gazing at the house themselves.

“Yes, you were right; they have settled in the Father Prebendary’s,” said Optimov. “His cherries are ripe now, so they have gone there to peck them.”

From the garden gate emerged the Father Prebendary himself, accompanied by the sexton. Seeing the attention directed upon his abode and wondering what people were staring at, he stopped, and he, too, as well as the sexton, began looking upwards to find out.

“The father is going to a service somewhere, I suppose,” said Potcheshihin. “The Lord be his succour!”

Some workmen from Purov’s factory, who had been bathing in the river, passed between the friends and the priest. Seeing the latter absorbed in contemplation of the heavens and the pilgrim women, too, standing motionless with their eyes turned upwards, they stood still and stared in the same direction.

A small boy leading a blind beggar and a peasant, carrying a tub of stinking fish to throw into the market-place, did the same.

“There must be something the matter, I should think,” said Potcheshihin, “a fire or something. But there’s no sign of smoke anywhere. Hey! Kuzma!” he shouted to the peasant, “what’s the matter?”

The peasant made some reply, but Potcheshihin and Optimov did not catch it. Sleepy-looking shopmen made their appearance at the doors of all the shops. Some plasterers at work on a warehouse near left their ladders and joined the workmen.

The fireman, who was describing circles with his bare feet, on the watch-tower, halted, and, after looking steadily at them for a few minutes, came down. The watch-tower was left deserted. This seemed suspicious.

“There must be a fire somewhere. Don’t shove me! You damned swine!”

“Where do you see the fire? What fire? Pass on, gentlemen! I ask you civilly!”

“It must be a fire indoors!”

“Asks us civilly and keeps poking with his elbows. Keep your hands to yourself! Though you are a head constable, you have no sort of right to make free with your fists!”

“He’s trodden on my corn! Ah! I’ll crush you!”

“Crushed? Who’s crushed? Lads! A man’s been crushed!”

“What’s the meaning of this crowd? What do you want?”

“A man’s been crushed, please your honor!”

“Where? Pass on! I ask you civilly! I ask you civilly, you blockheads!”

“You may shove a peasant, but you daren’t touch a gentleman! Hands off!”

“Did you ever know such people? There’s no doing anything with them by fair words, the devils! Sidorov, run for Akim Danilitch! Look sharp! It’ll be the worse for you, gentlemen! Akim Danilitch is coming, and he’ll give it to you! You here, Parfen? A blind man, and at his age too! Can’t see, but he must be like other people and won’t do what he’s told. Smirnov, put his name down!”

“Yes, sir! And shall I write down the men from Purov’s? That man there with the swollen cheek, he’s from Purov’s works.”

“Don’t put down the men from Purov’s. It’s Purov’s birthday to-morrow.”

The starlings rose in a black cloud from the Father Prebendary’s garden, but Potcheshihin and Optimov did not notice them. They stood staring into the air, wondering what could have attracted such a crowd, and what it was looking at.

Akim Danilitch appeared. Still munching and wiping his lips, he cut his way into the crowd, bellowing:

“Firemen, be ready! Disperse! Mr. Optimov, disperse, or it’ll be the worse for you! Instead of writing all kinds of things about decent people in the papers, you had better try to behave yourself more conformably! No good ever comes of reading the papers!”

“Kindly refrain from reflections upon literature!” cried Optimov hotly. “I am a literary man, and I will allow no one to make reflections upon literature! though, as is the duty of a citizen, I respect you as a father and benefactor!”

“Firemen, turn the hose on them!”

“There’s no water, please your honor!”

“Don’t answer me! Go and get some! Look sharp!”

“We’ve nothing to get it in, your honor. The major has taken the fire-brigade horses to drive his aunt to the station.”

“Disperse! Stand back, damnation take you! Is that to your taste? Put him down, the devil!”

“I’ve lost my pencil, please your honor!”

The crowd grew larger and larger. There is no telling what proportions it might have reached if the new organ just arrived from Moscow had not fortunately begun playing in the tavern close by. Hearing their favorite tune, the crowd gasped and rushed off to the tavern. So nobody ever knew why the crowd had assembled, and Potcheshihin and Optimov had by now forgotten the existence of the starlings who were innocently responsible for the proceedings.

An hour later the town was still and silent again, and only a solitary figure was to be seen the fireman pacing round and round on the watch-tower.

The same evening Akim Danilitch sat in the grocer’s shop drinking limonade gaseuse and brandy, and writing:

“In addition to the official report, I venture, your Excellency, to append a few supplementary observations of my own. Father and benefactor! In very truth, but for the prayers of your virtuous spouse in her salubrious villa near our town, there’s no knowing what might not have come to pass. What I have been through to-day I can find no words to express. The efficiency of Krushensky and of the major of the fire brigade are beyond all praise! I am proud of such devoted servants of our country! As for me, I did all that a weak man could do, whose only desire is the welfare of his neighbor; and sitting now in the bosom of my family, with tears in my eyes I thank Him Who spared us bloodshed! In absence of evidence, the guilty parties remain in custody, but I propose to release them in a week or so. It was their ignorance that led them astray!”

Written by Anton Chekhov