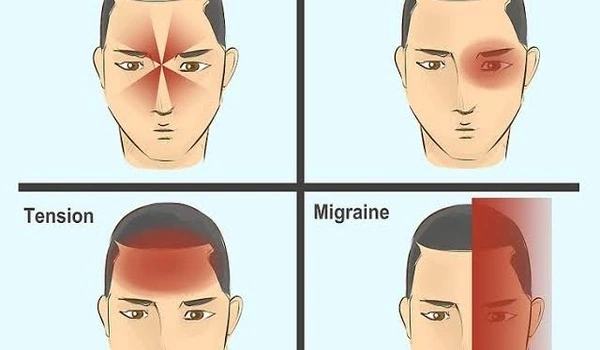

Migraine is a common neurological illness characterized by recurring headache attacks, which are frequently accompanied by symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, and sensitivity to light and sound. While migraine is not directly connected to pregnancy issues, several research has revealed a link between migraines and certain pregnancy complications.

Women are disproportionately impacted by migraine, particularly throughout their reproductive years. However, the link between migraine and unfavorable pregnancy outcomes is not well known. A recent study from Brigham and Women’s Hospital, a founding member of the Mass General Brigham healthcare system, reviewed data from thousands of women in the Nurses’ Health Study II to assess the association between migraine and pregnancy problems.

The team reports in Neurology that migraine diagnosed prior to pregnancy was connected to unfavorable pregnancy outcomes such as preterm delivery, gestational hypertension, and preeclampsia, implying that migraine may be a clinical signal of higher obstetric risk.

“Preterm delivery and hypertensive disorders are some of the primary drivers of maternal and infant morbidity and mortality,” said first author Alexandra Purdue-Smithe, PhD, an associate epidemiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and a Harvard Medical School instructor in Medicine.

“Our findings suggest that a history of migraine warrants consideration as an important risk factor for these complications and could be useful in flagging women who may benefit from enhanced monitoring during pregnancy.”

Our findings suggest that a history of migraines warrants consideration as an important risk factor for these complications and could be useful in flagging women who may benefit from enhanced monitoring during pregnancy.

Alexandra Purdue-Smithe

Women are two to three times more likely than males to suffer from migraine throughout their lifetime, and migraine is most common in women between the ages of 18 and 44. Aura (5.5% of the population) can accompany migraine headaches, which are usually visual abnormalities that develop before headache onset.

According to previous research, adverse pregnancy outcomes and migraine, particularly migraine with aura, are both consistently related to an increased risk of coronary heart disease and ischemic stroke in women. The underlying biology that causes these risks may also raise the likelihood of pregnancy problems. However, only a few small or retrospective studies have looked at migraines as a risk factor for pregnancy problems. No prospective studies have examined risks by aura phenotype (migraine with versus without aura).

Purdue-Smithe and colleagues analyzed data from the large, prospective Nurses’ Health Study II, which included 30,555 pregnancies from 19,694 U.S. nurses. Investigators looked at pre-pregnancy self-reported physician-diagnosed migraine and migraine phenotype (migraine with and without aura) and incidence of self-reported pregnancy outcomes.

Researchers were able to control for potential confounding factors such as body mass index, chronic hypertension, and smoking in their analyses due to the vast size of the study group and the availability of data on other health and behavioral factors.

When compared to no migraine, pre-pregnancy migraine was associated with a 17 percent higher risk of preterm delivery, a 28 percent higher rate of gestational hypertension, and a 40 percent higher rate of preeclampsia. Migraine with aura was linked to an increased incidence of preeclampsia compared to migraine without aura. Migraine was not linked to poor birth weight or gestational diabetes.

Participants with migraines who used aspirin regularly (at least twice a week) before to pregnancy had a 45 percent lower risk of preterm delivery. Individuals at high risk of preeclampsia and those with more than one intermediate risk factor for preeclampsia should take low-dose aspirin throughout pregnancy, according to the US Preventive Services Task Force. Low-dose aspirin during pregnancy has also been found in clinical trials to reduce premature birth rates. However, Purdue-Smithe points out that migraine is not currently listed as a reason for aspirin use during pregnancy.

“Our findings of reduced risk of preterm delivery among women with migraine who reported regular aspirin use prior to pregnancy suggests that aspirin may also be beneficial for women with migraine. Given the observational nature of our study and the lack of detailed information on aspirin dosage available in the cohort, clinical trials will be needed to definitively answer this question.”

Other study limitations include the fact that individuals only reported if they had a physician-diagnosed migraine, potentially omitting those who did not have chronic or severe migraine. Furthermore, aura was examined after the migraine diagnosis and after many of the pregnancies in the sample, which may have resulted in some degree of reverse causation in migraine phenotypic studies. Furthermore, the cohort research is made up primarily of non-Hispanic white people with relatively good socioeconomic position and health literacy, which may restrict generalizability.