According to new research, the atypical centriole in the sperm neck acts as a transmission system, controlling twitching in the sperm’s head and mechanically synchronizing the sperm tail movement to the new head movement.

According to the findings published in Nature Communications, the atypical centriole in the sperm neck functions as a transmission system that controls twitching in the sperm’s head, mechanically synchronizing the sperm tail movement to the new head movement.

The centriole has historically been considered a rigid structure that acts as a shock absorber.

“We believe the atypical centriole in the sperm’s neck is an evolutionary innovation whose function is to improve the movement of your sperm,” said Dr. Tomer Avidor-Reiss, professor of biological sciences in the UToledo College of Natural Sciences and Mathematics. “Reproductive success is determined by sperm’s ability to swim through female reproductive tract barriers while out-competing their competitors to fertilize the egg.”

Scientists at The University of Toledo discovered a new movement in sperm that provides innovative avenues for diagnostics and therapeutic strategies for male infertility.

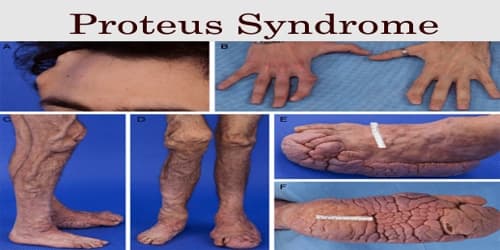

The research, led by Ph.D. candidate Sushil Khanal, builds on the lab’s previous ground-breaking discovery in human sperm, which changed reproductive biology dogma: During fertilization, a father donates not one, but two centrioles via sperm and the newly discovered sperm structure known as the atypical centriole may contribute to infertility, miscarriages, and birth defects.

“These findings call for a rethinking of our understanding of sperm centrioles in both sperm movement and the early embryo,” Avidor-Reiss said. Avidor-Reiss believes that this discovery will open up new avenues for helping families understand why they are having difficulty conceiving. If the sperm’s head and tail aren’t moving together, the sperm won’t be able to move efficiently enough to reach the egg.

“If the centriole is faulty, this coupling between the sperm tail and head will be faulty,” Avidor-Reiss explained. “In a patient where we don’t know what’s wrong, we could potentially reverse engineer the way the sperm’s tail moves to determine centriole functionality to determine the couple’s infertility.”

He also stated that discovering this movement could be used in the future to predict which sperm have a healthy centriole capable of supporting life. “Right now, no one knows what to fix,” Avidor-Reiss explained. “We’ve found the source of the problem. This information enables us to identify a previously unknown subgroup of infertile men.”

According to the new findings, there is a cascade of internal sliding formations in the atypical distal centriole, typical proximal centriole, and surrounding material in mammalian sperm that links tail beating with asymmetric head kinking.

The researchers were able to show that the left and right sides of the atypical centriole move about 300 nanometers relative to each other using a STORM immunofluorescent microscope in the UToledo Instrumentation Center. Even though it’s a small number, it represents significant movement in a cell, given that the average protein diameter is five nanometers.

Luke Achinger, a Ph.D. student who recently graduated from UToledo with a bachelor’s degree in biology, sang bass in the University’s premier choral ensemble as an undergraduate and wrote lyrics about his lab’s new discovery, explaining how the new movement works in a song called “Twitch, Roll, and Yaw.”

“We enjoy promoting science and art, and in this case, we demonstrate that sperm beats in unison. The sperm’s head is not separated from the tail. The neck, which includes both atypical and typical centrioles, may function as a morphological computer or sperm brain, coordinating sperm movement “Avidor-Reiss stated.

“The song is a unique way to comprehend a significant change. Over the last billion years, the centriole has always looked the same. It is one of the cell’s most conservative structures. We discovered something new that works in the opposite direction, evolving from a shock absorber to a transmission system.”

Dr. Tzviya Zeev-Ben-lab Mordehai’s at Utrecht University in the Netherlands performed cutting-edge cryo-electron microscopy of the sperm neck, and Hermes Bloomfield-Gadêlha at the University of Bristol in the United Kingdom performed mathematical and waveform analysis.