Milk is tested on a regular basis, and antibiotics are very rarely found. In fact, less than two out of every 10,000 tankers tested positive for milk in 2016. (National Milk Drug Residue Database). Antibiotic-laced milk is discarded. Farmers follow Federal guidelines on how long they must discard a cow’s milk after she has been treated with antibiotics to avoid drug residues in milk. If a drug label does not specify how long milk should be discarded, the farmer must consult with a veterinarian to determine the appropriate time.

Consumers would be willing to buy milk from cows only treated with antibiotics when medically necessary—as long as the price isn’t much higher than conventional milk, according to researchers at the College of Veterinary Medicine.

The findings suggest conventional farmers could tap a potentially large market for this type of milk if they can find the right price point—and that dairy consumers can help slow the rise of antimicrobial resistance.

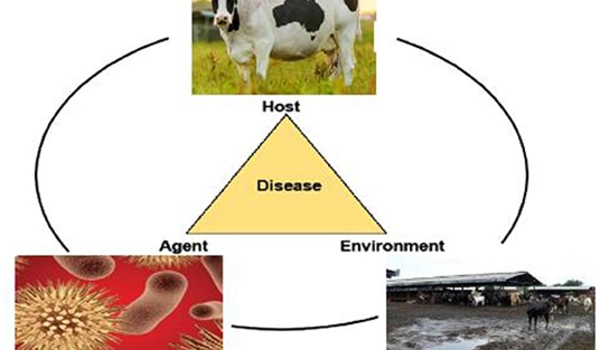

“Most of the antibiotics produced throughout the world are used for animal agriculture. Therefore, reducing antibiotic use in animals, including dairy cattle, is necessary to tackle antibiotic resistance at a global scale,” said Dr. Renata Ivanek, professor in the Department of Population Medicine and Diagnostic Sciences. She is senior author on the study, which published in the Journal of Dairy Science.

Most of the antibiotics produced throughout the world are used for animal agriculture. Therefore, reducing antibiotic use in animals, including dairy cattle, is necessary to tackle antibiotic resistance at a global scale.

Dr. Renata Ivanek

In the paper, the researchers propose a new label for milk that indicates responsible antibiotic use (RAU), which would leverage consumer preferences to reduce the use of antibiotics on commercial dairy farms. The study showed that, although a consumer’s willingness to pay for the RAU-labeled milk was comparable to how much they would pay for the unlabeled milk, they strongly preferred the RAU-labeled milk over the unlabeled milk option.

Therefore, the researchers hypothesize this new RAU label would entice farmers to minimize antibiotics more than they do for conventional, unlabeled milk. Too much antibiotic treatment in cows leads to the rise of resistant strains of bacteria, which can make antibiotics for both animals and humans less effective, the researchers note.

“Consumers should know that their choices are important, and that their understanding of antibiotic use could move the dairy industry toward more sustainable milk production practices,” said Dr. Ece Bulut, research associate in the Department of Population Medicine and Diagnostic Sciences and co-author of the study.

The researchers conducted a nationally representative survey of U.S. adults, finding that half were willing to buy RAU-labeled milk. They also held a randomized, experimental auction with real money and milk, which showed that buyers were also willing to pay for RAU-labeled milk but only slightly more than they are willing to pay for the unlabeled cartons.

“What this means is that there could potentially be a large market for RAU milk as long as the price isn’t much higher than conventional milk, so it’s a possible new option for conventional farmers,” said Robert Schell, M.S. ’19, first author of the study.

A similar label for certified responsible antibiotic use (CRAU) is already used in the poultry industry, Bulut said. CRAU limits the use of medically important antibiotics—antibiotics used in human medicine—in poultry production. The researchers envision that the RAU label would similarly be determined by veterinarians and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) standards, so that any carton of milk with an RAU label would come from a cow treated with antibiotics only when medically necessary.

“The existing literature suggests that larger bodies regulating these sorts of claims, like the USDA and CRAU certification, makes consumers more willing to trust and, as a result, buy products with desirable labels,” said Schell, a doctoral student at the School of Public Health in University of California, Berkeley, who started working on the study as a master’s degree student at the Charles H. Dyson School of Applied Economics and Management.

This study is an important initial step in exploring consumer attitudes toward an RAU label and its potential market for conventional farmers, the researchers said.