One of the few archaeological sites in the Americas that has well-preserved plant remnants dating back 11,000 years is the El Gigante rockshelter in western Honduras.

Considered one of the most important archaeological sites discovered in Central America in the last 40 years, El Gigante was recently nominated as a UNESCO World Heritage site.

“No other location shows, as clearly as El Gigante,” state UNESCO materials about the site’s universal value, “the dynamic character of hunter-gatherer societies, and their adaptive way of life in the Central American highlands, and in Mesoamerica broadly during the early and middle Holocene.”

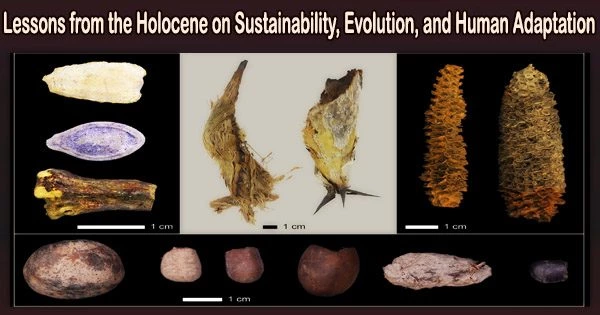

Now, anthropologists Richard George, a postdoc at UCSB, and Douglas Kennett and Amber VanDerwarker of UC Santa Barbara have excavated and examined botanical macrofossils from El Gigante using cutting-edge technology, including maize cobs, avocado seeds, and rinds. Their results are published in the journal PLOS ONE.

“Our work at El Gigante demonstrates that the early use and management of tree crops like wild avocado and plums by at least 11,000 years ago,” Kennett said, “set the stage for the development of later systems of aboriculture that, when combined with field cropping of maize, beans and squash, fueled human population growth, the development of settled agricultural villages and the first urban centers in Mesoamerica after 3,000 years ago.”

With 375 radiocarbon dates, the study offers a significant update to the timeline of tree and field crop use found in the El Gigante. It reveals that squash and tree fruits first appeared around 11,000 years ago, with the majority of other field crops following later maize around 4,500 years and beans around 2,200 years.

Our work shows that different types of agricultural systems supported human populations in Central America and that some were more sustainable than others. Forest management and arboriculture persisted for thousands of years before it was eclipsed in importance by the expansion of maize farming after 4,000 years ago. The archaeological record provides an archive of human adaptation that should be considered in the context of anthropogenic alteration of our Earth’s climate today. These ancient archives could help rural farmers in Central America adapt to changing conditions moving into the future.

Douglas Kennett

The initial focus on tree fruits and squash, Kennett noted, is consistent with early coevolutionary partnering with humans as seed dispersers in the wake of megafaunal extinction in Central America.

The majority of the Holocene was dominated by tree crops, but approximately 4,000 years ago there was a general transition to field crops, which was mostly fueled by a greater emphasis on maize farming.

“The transition to agriculture is one of the most significant transformations of our Earth’s environmental and cultural history,” Kennett said. “The domestication of plants and animals in multiple independent centers worldwide resulted in a major demographic transition in human populations that fueled the transition to more intensive forms of agriculture during the last 10,000 years. Agriculture also provided the economic foundation for urbanism and the development of state institutions after 5,000 years ago in many of these same regions.”

The botanical materials at El Gigante, remarkably well preserved, reflect the transition from foraging to farming, providing a rare glimpse of early foraging strategies and changes in subsistence.

El Gigante serves as a macrobotanical archive for interactions and the flow of domesticated plants between Mesoamerica, Central America, and South America. The authors note that El Gigante is unique in its location along the southern periphery of Mesoamerica and for its lower elevation than the dry caves of central Mexico.

Even more broadly, it enables scientists to investigate the long-term evolutionary and demographic processes associated with the domestication of various tree and field crops.

“The quality of the plant preservation at El Gigante is simply unmatched, giving us a deeper understanding of how ancient Hondurans managed their forests, domesticated a variety of plant species and intensified their cultivation of key resources over millennia,” said VanDerwarker. “What seems clear is that practices of forest management and field cultivation were closely linked and evolved in tandem.”

And therein, Kennett added, some lessons for modern society can be inferred.

“Our work shows that different types of agricultural systems supported human populations in Central America and that some were more sustainable than others,” he said.

“Forest management and arboriculture persisted for thousands of years before it was eclipsed in importance by the expansion of maize farming after 4,000 years ago. The archaeological record provides an archive of human adaptation that should be considered in the context of anthropogenic alteration of our Earth’s climate today. These ancient archives could help rural farmers in Central America adapt to changing conditions moving into the future.”