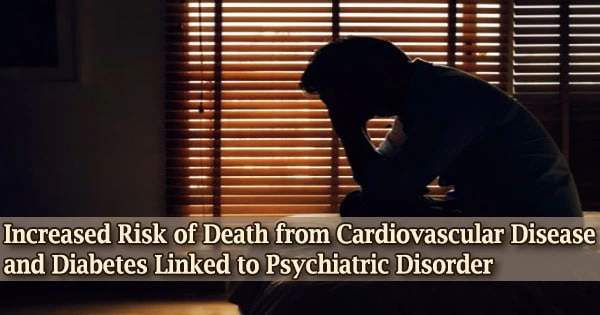

According to a new study by Seena Fazel of the University of Oxford in the UK and colleagues, those with chronic, non-communicable diseases are more than twice as likely to die if they also have psychiatric comorbidity.

Non-communicable diseases like diabetes and heart disease are a global public health issue since they are thought to be responsible for an additional 40 million deaths per year. The area of medicine that focuses on mental, emotional, and behavioral diseases is called psychiatry.

Therefore, a “psychiatric disorder” is a general phrase that covers a wide range of issues that interfere with a person’s thoughts, feelings, behavior, or mood. Psychiatric diseases, also known as “mental illness” and “mental health issues,” can have a serious impact on a person’s capacity to perform at job or school or uphold healthy social relationships.

Mental illness is a medical problem, not a sign of weakness. The most effective therapies for psychiatric diseases differ from person to person and rely on the precise disorder as well as the extent and severity of the symptoms.

In the latest study, researchers examined more than 1 million patients with chronic lung disease, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes who were born between 1932 and 1995 using national registers in Sweden. In the analysis, 25–32% of the participants had a lifetime diagnosis of any psychiatric disease in addition to their primary diagnosis.

Anxiety and depressive disorders were the most prevalent mental disorders, affecting 1 in 8 persons, or 970 million people worldwide, in 2019. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of people who suffer from anxiety and depressive illnesses greatly increased in 2020.

7% (range 7.4% -10.8%; P<0.001) of the study participants had died within 5 years after diagnosis, whereas 0.3 percent (0.3 percent -0.3 percent; P<0.001) had committed suicide. Comparing those with comorbid psychiatric problems to those without them, there was a higher all-cause mortality rate of 15.4% to 21.1%. (5.5 percent -9.1 percent).

Improving assessment, treatment, and follow-up of people with comorbid psychiatric disorders may reduce the risk of mortality in people with chronic non-communicable diseases. We used electronic health records to investigate over 1 million patients diagnosed with chronic lung diseases, cardiovascular diseases, and diabetes.

Seena Fazel

Psychiatric comorbidity was consistently linked to higher rates of premature mortality and suicide, even after the researchers controlled for familial risk factors by comparing each patient with an unaffected sibling (adjusted HR range: aHRCL=7.2 (95 percent CI: 6.8-7.7; P<0.001) to aHRCV =8.9 (95 percent CI: 8.5-9.4; P<0.001).

According to preliminary projections, major depressive disorders and anxiety disorders will both rise by 26 and 28 percent in just one year, respectively. Although there are effective methods for both prevention and therapy, the majority of those who suffer from mental illnesses do not have access to them. Stigma, prejudice, and human rights violations are also commonplace.

Depending on the mental diagnosis, the risks varied; for example, death risks were increased by 8.3–9.9 times in people with co-occurring substance use disorder compared to unaffected siblings and by 5.3–7.4 times in those with co-occurring depression.

The use of population-based registries to identify patients results in the diagnosis of mental comorbidities in speciality care settings, potentially missing undiagnosed persons and those with less severe psychiatric disorders. This is one limitation of the study.

“Improving assessment, treatment, and follow-up of people with comorbid psychiatric disorders may reduce the risk of mortality in people with chronic non-communicable diseases,” the authors say. “We used electronic health records to investigate over 1 million patients diagnosed with chronic lung diseases, cardiovascular diseases, and diabetes,” Fazel adds.

“More than 7% of the patients died of any cause within five years and 0.3% died from suicide risks that were more than doubled in patients with psychiatric comorbidities compared to those without such comorbidities.”