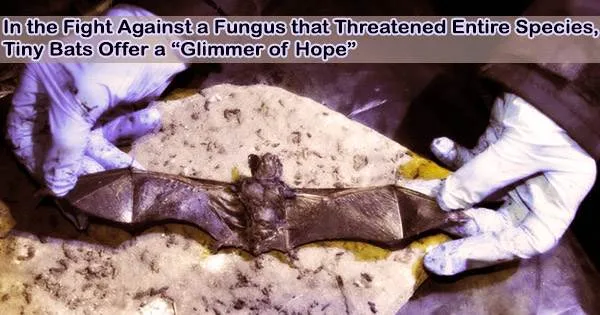

Thousands of hairy, chocolate-brown critters are stirring deep inside a damp, cold cave in Vermont. The small brown bats hibernated last fall after a devastating infection wiped out most of their population.

They’re waking up now in the first few days of May, leaving their rock wall roosts, and taking their first hesitant flights in quest of the moths, beetles, and flying aquatic insects they eat.

One of the first North American outbreaks of the fungus that causes white nose syndrome was discovered here, in hidden crevices deep within a Vermont mountain. Bat bones litter the cave floor like dry lawn-mower cuttings. Look closer and you’ll find tiny skulls.

And the bats are still dying.

White nose syndrome is caused by an invasive fungus first found in an upstate New York cave in 2006, a short bat flight from the Dorset, Vermont, colony. In order to find food, the fungus awakens bats from their hibernation and sends them into the chilly winter air. Because there aren’t enough insects around at that time of year to sustain them, they either perish from exposure or famine.

The Dorset bats, which are smaller than mice and weigh around three pennies in the palm, scurry across the cave walls or cling to one another for warmth. Their wellbeing suggests that, at least in some species, the fungus that has killed millions of their brethren across North America is being adapted to.

“That’s really significant, because it seems to be a stronghold where these bats are mostly surviving and then spreading out throughout New England in the summer,” said Alyssa Bennett, a small mammal biologist for the Vermont Department of Fish and Wildlife. She has studied bats and white nose syndrome for more than a decade.

“We’re hoping that it’s a source population for them to recover,” Bennett said as critters flitted and swooped around her.

There’s something special about those bats. We can’t tell exactly what that is, but we have genetic research that we’ve collaborated on that suggests those bats do have factors that are related to hibernation and immune response that are allowing them to tolerate this disease and pass those features on to their young.

Alyssa Bennett

It will take time. Little brown bat females birth only one pup a year. And while they can live into their teens or 20s, only 60% to 70% of pups make it beyond their first 12 months, Bennett said.

Scientists now estimate that between 70,000 and 90,000 bats hibernate in the Dorset cave, the largest concentration in New England. In the 1960s, the last time the area was studied before white nose entered, they were thought to have a winter population of 300,000 to 350,000 people, but that number has since dropped to 350,000 or less.

The extent of the population decline after the fungus took hold is unknown, but biologists who went in 2009 or 2010 saw the ground outside the cave was covered in dead bats.

It is thought that the fungus that causes white nose syndrome was imported to North America from Europe, where bats were already familiar with it. The fungus, so named because it causes white, fuzzy spots on bat noses and other body parts, has wiped off 90% or more of the bat populations in some parts of North America.

Last month, a report by the North American Bat Conservation Alliance found that 81 of the 154 known bat species in the United States, Canada and Mexico are at severe risk from white nose infection, climate change and habitat loss.

It matters. The U.S. Geological Survey estimates that bats boost U.S. agriculture by $3.7 billion a year by eating crop-destroying insects such as larvae-laying moths, whose offspring bore into corn plants.

Since many tiny brown bats appeared to survive exposure to the fungus, despite an overall mortality rate that was thought to threaten their extinction, scientists have recognized this. Though Dorset’s little brown bats are holding on, other once common species found with them, like northern long eared or tricolor bats, are almost impossible to detect there now, Bennett said.

“There’s something special about those bats,” Bennett said of Dorset’s little browns. “We can’t tell exactly what that is, but we have genetic research that we’ve collaborated on that suggests those bats do have factors that are related to hibernation and immune response that are allowing them to tolerate this disease and pass those features on to their young.”

Winifred Frick, chief scientist at Bat Conservation International, who has followed white nose syndrome’s march across North America, said the fungus has been found in 38 states so far. She says it’s a “gut punch” each time she hears of a new outbreak.

Colorado reported its first infected bats earlier this year.

Even though the return is so far only a small portion of earlier numbers, Frick is glad that bats are starting to repopulate some locations where carcasses once piled up.

“That’s a real glimmer of hope,” she said.

In addition to Vermont, other areas near where white nose was first discovered also report stable, possibly rising numbers of little brown bats.

Pennsylvania lost an estimated 99.9% of its population after white nose struck, said Greg Turner, the state mammal expert for the Pennsylvania Game Commission. While the numbers are still low, they’re slowly increasing in some places. One old mine in Blair County had just seven bats in 2016. This year, there were more than 330.

“I’m feeling pretty comfortable,” Turner said. “We’re not going to be stuck staring down the barrel of extinction.”

His research shows bats that hibernate at colder temperatures do better against white nose because the fungus grows more slowly.

Though scientists are still unsure of the process that keeps certain creatures alive while so many perish, this may suggest that the bats are less likely to awaken from the irritation it creates.

“By selecting colder temperatures, they’re helping themselves in two ways, they’re helping themselves preserve fat and preserve their energy and they’re also getting less disease,” Turner said.

Still, there are worrying trends. Pennsylvania’s bat population is a tiny fraction of what it was before white nose invaded. In some locations, Turner and his colleagues see more bats, but inexplicably few females.

In Virginia, populations have decreased by more than 95%, however certain colonies are beginning to stabilize or modestly increase in size. However, that’s happening at only a fraction of the sites once monitored, said Rick Reynolds, a non-game mammal biologist with the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources.

“We remain positive, but there is a long road ahead with much uncertainty,” Reynolds said in an email.

Back in Vermont, where temperatures in the Dorset cave fall into the low 40s (around 4.4 degrees Celsius) in winter, the bats seem to have found a sweet spot cold enough to slow growth of the fungus.

Bennett is working with Laura Kloepper, a bioacoustics expert from the University of New Hampshire, to get a better handle on the population count. This year, they’re attempting to obtain a baseline population estimate using acoustic modeling to compare sound records with thermal imaging. They’ll survey using the same method again next year to try to determine the change.

“We want to try to understand what we can possibly do to save not only the species of bat, not only the bats at this cave, but really bats around the world,” Kloepper said.