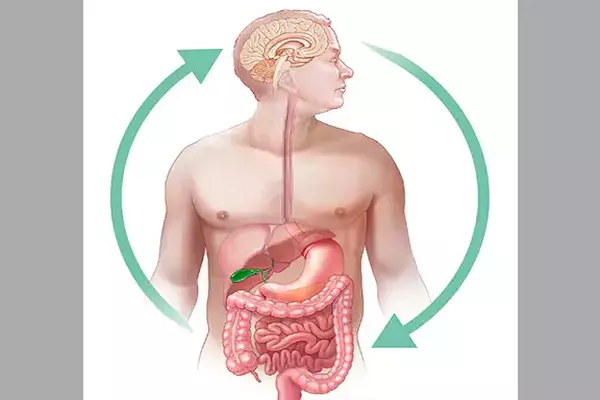

Intestinal diseases are those that affect any segment of the intestine (small or large), from the duodenum to the rectum. The term encompasses acute or chronic conditions and a wide range of diseases such as constipation, diverticular disease, and irritable bowel syndrome.

Bacteria in the small intestine adapt dynamically to our nutritional state, with individual species disappearing and reappearing. For the first time, researchers have been able to study the bacteria of the small intestine and their unique adaptability in depth. The findings contribute to a better understanding of intestinal diseases such as Crohn’s disease and Celiac disease, as well as the development of new therapeutic approaches.

Humans have as many microbes in their microbiota as there are cells in their bodies, with the majority of these found in the large intestine (colon). They are an important part of our ‘digestion’ because they can extract energy from foods that our digestive enzymes cannot digest. Unfortunately, while collecting fecal samples is simple, studying the lower small intestine has been difficult because it can only be reached during a surgical procedure or after purging the intestinal contents to allow safe passage of an endoscope.

Despite the fact that the small intestine is essential for life and absorbs 90% of all our calories, the small intestinal microbiome has remained almost “terra incognita” within the human gastrointestinal tract. Researchers from the Department of Biomedical Research at the University of Bern and the University Clinic for Visceral Surgery and Medicine at the Inselspital, led by Andrew Macpherson and Bahtiyar Yilmaz, have now been able to examine the intestinal bacteria of the human small intestine in a simple and innovative way to show how they support the digestive process by reacting dynamically to the human nutritional status.

We think of these changes in the intestinal bacteria in the small intestine as an ecosystem. Because the system is so adaptable, each bacterial species can adapt to a changing environment in the small intestine by changing the proportions of subspecies, preventing the species as a whole from dying out.

Andrew Macpherson

While the gut bacteria (microbiota) of the large intestine remain relatively stable throughout life, those in the small intestine have been shown to be very unstable: they largely disappear when we fast overnight and reappear when we eat in the morning. These findings are important for a better understanding of the development of intestinal diseases such as celiac disease or Crohn’s disease. The study is published in the journal Cell Host and Microbe.

Direct access to intestinal bacteria

The researchers were able to examine patients who had cancer surgery in their lower small intestine (ileum). After these patients have healed, the ileum may end as an artificial opening in the abdominal wall in some cases. The researchers were able to examine what was happening in “real time” because they had direct access to the small intestinal bacteria.

The bacterial samples were analyzed using cutting-edge sequencing techniques. It was discovered that the number of bacteria in the ileum is heavily influenced by the patient’s nutritional status: periods without food significantly reduce the number of bacteria in the small intestine. The bacteria “bloom” again after a meal. Despite these diet-related fluctuations in “biomass,” the various types of bacteria do not become extinct, even if their numbers are very small.

“Rather, each species is made up of a large number of subspecies that coexist – much like the different variants of COVID-19 that appear and disappear in the human population and the proportions of each subspecies change very quickly, even within hours of eating a meal,” said Dr. Bahtiyar Yilmaz, first author and corresponding author of the study.

Effective and simple method

The close collaboration between clinic and basic research, that exists between the University Hospital Bern and the University of Bern, proved to be particularly valuable here: “The availability of different types of samples, combined with an unprecedented documentation of the clinical details by the medical staff of the University Hospital Bern and the in-depth microbial sequencing with the University of Bern’s next-generation sequencing platform make our study unique,” says Yilmaz.

The results show that the use of ‘ostomy samples is very effective and simple to characterize the intestinal flora of the small intestine. The researchers were also able to demonstrate that the samples from patients with a stoma of the small intestine are representative of the intestinal flora of the small intestine without surgery.

“Ecosystem” in the small intestine

“We think of these changes in the intestinal bacteria in the small intestine as an ecosystem,” said Andrew Macpherson, the study’s head and senior author. “Because the system is so adaptable, each bacterial species can adapt to a changing environment in the small intestine by changing the proportions of subspecies, preventing the species as a whole from dying out.”

In this way, the intestinal bacteria prevent species extinctions unless there are “bottlenecks” caused by illness, malnutrition, or environmental pollution. The findings may help to understand the interactions between the host and intestinal bacteria in intestinal diseases such as Crohn’s disease, celiac disease, or chronic inflammation of the large intestine (ulcerative colitis), and may form the basis for new therapeutic approaches.