Tissues frequently fail to heal after catastrophic muscle-loss traumas such as gunshot wounds and car accidents, according to new research in mice from the University of Michigan. The findings point to new therapeutic techniques that, in the long run, could restore function and prevent limb loss.

Skeletal muscle is the tissue that defines how we move and communicate, and it is capable of self-repair via stem cells following injury. This, however, does not occur when considerable amounts of muscle are destroyed, a condition known as volumetric muscle loss. Despite their ubiquity, little is known about why these injuries continuously surpass the body’s natural regeneration processes. And there are no agreed-upon standards of care for dealing with them in the medical community.

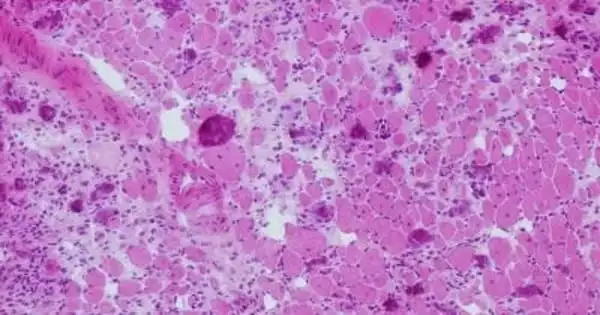

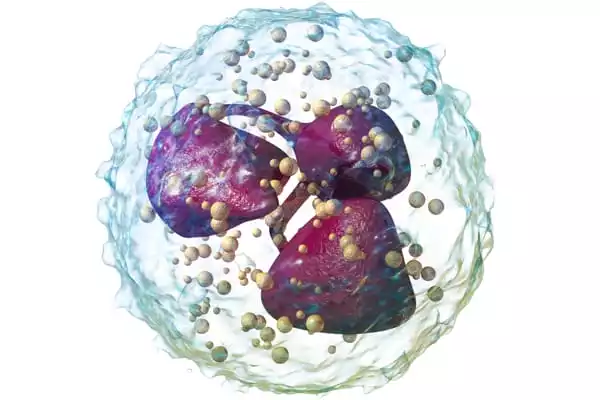

The inflammatory response is critical for skeletal muscle regeneration. The intricate process of muscle recovery is orchestrated by a diverse range of innate and adaptive immune cells. Skeletal muscle injury or disease can trigger an inflammatory response in which phagocytes and lymphocytes penetrate the tissue and alter satellite cell activation, proliferation, and terminal differentiation. Muscle cells begin to necrosis immediately after injury. When the sarcolemma is damaged, the contents of the cell are discharged into the extracellular space. Infiltrating immune cells, such as neutrophils and macrophages, begin clearing up necrotic cell debris and emit a variety of growth factors and cytokines in order to attract more immune cells to the site of injury.

The persistence of neutrophils at the injury site limits the ability of muscle stem cells to produce new and repair existing muscle fibers. The fact that natural killer cells are inhibiting inflammation caused by neutrophils is a new role for what they might be doing.

Jacqueline Larouche

U-M researchers studied volumetric muscle loss injuries in mice alongside partners from Georgia Tech, Emory University, and the University of Oregon to better understand why these injuries do not recover.

White blood cells of various sorts help to repair muscle injuries by clearing debris and signaling to stem cells to coordinate regeneration. The latest findings, however, show that immune cells become dysregulated and inhibit stem cell restoration. For example, the University of Michigan team discovered that following volumetric muscle loss injuries that do not heal, neutrophils (a type of white blood cell) stay at the wounded region longer than usual.

“The persistence of neutrophils at the injury site limits the ability of muscle stem cells to produce new and repair existing muscle fibers,” said Jacqueline Larouche, a U-M Ph.D. student in biomedical engineering and the paper’s first author in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

In addition to the neutrophils failing to execute their functions, the team discovered that they were being killed by other immune cells. This is illogical, according to Carlos Aguilar, an assistant professor of biomedical engineering at the University of Michigan. Neutrophils were found communicating with natural killer cells using single-cell RNA sequencing and imaging. These natural killer cells effectively caused neutrophils to self-destruct. Different healing results are attainable by changing how the two cell types communicate.

“The fact that natural killer cells are inhibiting inflammation caused by neutrophils is a new role for what they might be doing,” Aguilar said.

Alex Smith, a former NFL quarterback, is one of the most well-known cases of volumetric muscle loss. Smith suffered a devastating complex fracture during a game in 2018, fracturing both the tibia and fibula in his right leg. Within days, physicians noticed a rare bacterial infection called necrotizing fasciitis spreading in the wound, and they had to remove a significant amount of his muscular tissue. Smith’s return to the field took 17 surgeries and nearly two years, dubbed a “miracle” recovery by many.

Many injuries incurred during athletic training or competition necessitate a lengthy period of limb immobilisation (muscle disuse). Such durations cause skeletal muscle atrophy and, as a result, impairments in metabolic health and functional performance, especially in the early stages (1-2 weeks) of muscular disuse. The extent of muscle loss during injury has a significant impact on the level and duration of rehabilitation required.

The team thinks that improved treatments will mean that recovery from these injuries will no longer be miraculous. The research was supported by the US Department of Defense’s Congressionally Directed Medical Research program and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency.