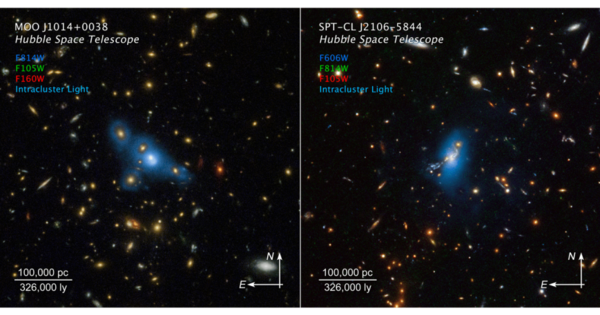

The Hubble Space Telescope has observed a phenomenon known as “ghost light” in distant galaxies, which is believed to be the result of ancient star formation. This light, also known as “extragalactic background light,” has been found to stretch back in time to when the universe was only a few hundred million years old. This discovery provides new insights into the early history of star formation in the universe.

Countless stars wander among the galaxies like lost souls, emitting a ghostly haze of light in massive clusters of hundreds or thousands of galaxies. These stars are not gravitationally bound to any of the cluster’s galaxies.

For astronomers, the nagging question has been: how did the stars become so dispersed throughout the cluster in the first place? Several competing theories contend that the stars were stripped out of a cluster’s galaxies, tossed around after galaxies merged, or were present early in a cluster’s formative years many billions of years ago.

A recent infrared survey from NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope, which looked for this so-called “intracluster light,” sheds new light on the mystery. The new Hubble observations suggest that these stars have been wandering around for billions of years, and are not a product of more recent dynamical activity inside a galaxy cluster that would strip them out of normal galaxies.

Understanding the origin of intracluster stars will help us understand the assembly history of an entire galaxy cluster, and they can serve as visible tracers of dark matter enveloping the cluster.

Hyungjin Joo

The survey included ten galaxy clusters that were nearly 10 billion light-years away. Because the faint intracluster light is 10,000 times fainter than the night sky as seen from the ground, these measurements must be taken from space.

Looking back billions of years, the survey reveals that the fraction of intracluster light relative to total light in the cluster remains constant. “This means that these stars were already homeless in the early stages of the cluster’s formation,” said Yonsei University’s James Jee in Seoul, South Korea. His findings will be published in the issue of Nature.

Stars can be scattered outside of their galactic birthplace when a galaxy moves through gaseous material in the space between galaxies, as it orbits the center of the cluster. In the process, drag pushes gas and dust out of the galaxy. However, based on the new Hubble survey, Jee rules out this mechanism as the primary cause for the intracluster star production. That’s because the intracluster light fraction would increase over time to the present if stripping is the main player. But that is not the case in the new Hubble data, which show a constant fraction over billions of years.

“We don’t know what caused them to become homeless. Current theories are unable to explain our findings, but they were produced in large quantities in the early universe” Jee stated. “Galaxies may have been quite small in their early formative years, and they bled stars quite easily due to a weaker gravitational grasp.”

“Understanding the origin of intracluster stars will help us understand the assembly history of an entire galaxy cluster, and they can serve as visible tracers of dark matter enveloping the cluster,” said the paper’s first author, Hyungjin Joo of Yonsei University. Dark matter is the universe’s invisible scaffolding that holds galaxies and clusters of galaxies together.

If the wandering stars were created by a relatively recent pinball game between galaxies, they would not have had enough time to scatter across the entire gravitational field of the cluster and thus would not be able to trace the distribution of the cluster’s dark matter. However, if the stars were born in the early years of the cluster, they will have fully dispersed throughout the cluster. This would allow astronomers to map the distribution of dark matter across the cluster using the errant stars.

By measuring how the entire cluster warps light from background objects due to a phenomenon known as gravitational lensing, this technique is novel and complementary to the traditional method of dark matter mapping.

Intracluster light was discovered in the Coma cluster of galaxies in 1951 by Fritz Zwicky, who reported that observing luminous, faint intergalactic matter in the cluster was one of his most interesting discoveries. Zwicky was able to detect the ghost light even with a modest 18-inch telescope because the Coma cluster, which contains at least 1,000 galaxies, is one of the closest clusters to Earth (330 million light-years).

The near-infrared capability and sensitivity of NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope will greatly extend the search for intracluster stars deeper into the universe, and thus should aid in solving the mystery.