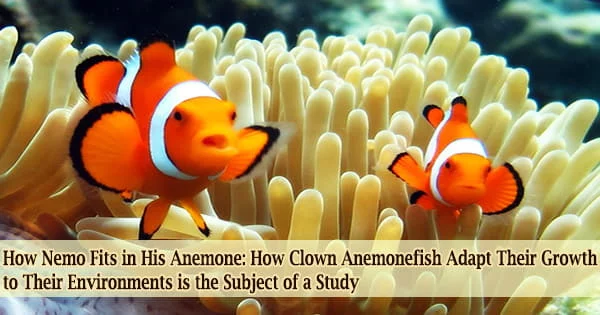

Clown anemonefish can manage their growth to match the size of the anemone host, according to research. The stinging tentacles of anemones don’t disturb the clownfish, though. It actually calls the tentacles home.

Clown anemonefish were paired with anemones of varying sizes by researchers from Newcastle and Boston Universities to study the relationship between the size of the fish and the anemone. Fish on larger anemones grow more quickly than fish on smaller anemones, they discovered.

The findings provide the first experimental proof that vertebrate development plasticity reacts to a mutualistic relationship (where both parties gain), and they also provide an explanation for the strong correlation between anemonefish size and anemone size in the wild.

The researchers write about their findings in the journal Scientific Reports and contend that given their environment of anemones, anemonefish probably maximize their reproductive potential by controlling their growth.

Food and space availability alone are ruled out as potential mechanisms by the scientists. One hypothesis for the pattern is that it is a result of space availability and a biological trigger from the mutualistic host. Future research will focus on the specific mechanism underlying the phenomena.

Lead author, Dr. Theresa Rueger, Lecturer in Tropical Marine Biology at Newcastle University’s School of Natural and Environmental Sciences, said: “Anemonefishes are fascinating for their ability to adjust their growth rate to their specific environments, whether that’s to avoid conflict with a larger fish or, as we show here, to make sure they are the ideal size for their anemones.”

Our data from wild fish shows that anemone size and fish size is very closely correlated: large fish are always on large anemones. And our experiment shows that is not a coincidence that the fish actively regulate their growth to fit their anemone host. This is the first time that this plasticity of growth in a vertebrate has been found to depend on a mutualistic partner, and it shows how important mutualisms are.

Dr. Theresa Rueger

The clown anemonefish finds protection among the anemone’s tentacles from predators who won’t approach the stinging guardian. The leftovers from the anemone’s meals are likewise available to the anemonefish.

Fish need anemones because they shield them from predators, and larger anemones provide the fish more room to swim about and feed while remaining safe.

The fish might not obtain enough food or be safe if it grows too large for the anemone it is on. The fish also desires to grow in size so that it can have a large number of offspring.

“Our data from wild fish shows that anemone size and fish size is very closely correlated: large fish are always on large anemones. And our experiment shows that is not a coincidence that the fish actively regulate their growth to fit their anemone host. This is the first time that this plasticity of growth in a vertebrate has been found to depend on a mutualistic partner, and it shows how important mutualisms are.”

“The next step will be to disentangle the mechanism, what makes the fish decide how large it needs to be? Through our experiment, we already know it’s not food availability (all fish got the same amount of food) and it is not space availability alone (the fish did not show the same plasticity when they were on silicone anemones), so it seems to be something about the mutualistic partner itself. Lots of research still to be done!”

Other mutualistic relationships most likely have the capacity to foresee the ideal body size in respect to the mutualistic partner. The interaction of mutualistic partners and its impact on animal growth regulation and developmental phenotypic plasticity will be the main topics of future research.