With ominous orange-gray smoke clouds looming on the western horizon, it’s easy to see how Colorado’s highest city and other mountain communities are directly threatened by climate change. The snowpack on the mountains is shrinking and melting earlier in the spring. Warmer and longer summers dry out vegetation, increasing the risk of wildfires in western mountain forests, where the fire season has increased by at least one month since 1979.

Mountain landscapes all over the world are at risk of becoming more dangerous to communities surrounding them as a result of climate change, while their accelerated evolution may bring additional environmental risks to surrounding areas.

This is according to a scientist from the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa, who highlights the sensitivity of mountains to global climate change in a new study on the eve of the COP27 climate meeting. Professor Jasper Knight of Wits University’s School of Geography, Archaeology, and Environmental Studies demonstrates how complex mountain systems respond to climate change in very different and sometimes unexpected ways, and how these responses can affect mountain landscapes and communities.

As snow and ice shrink, mountain land surfaces are getting darker and this dramatically changes their heat balance, meaning they are warming up faster than the areas around them. Therefore, climate change impacts are bigger on mountains than they are anywhere else. This is a real problem, not just for mountains but also for the areas around them

Professor Jasper Knight

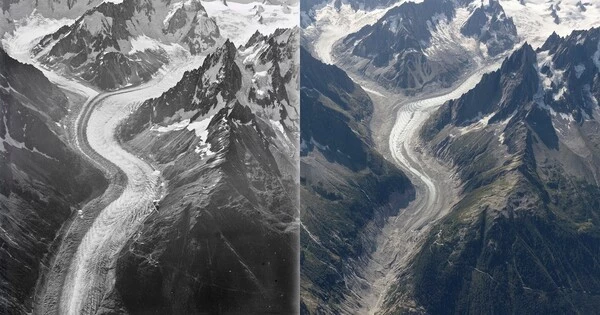

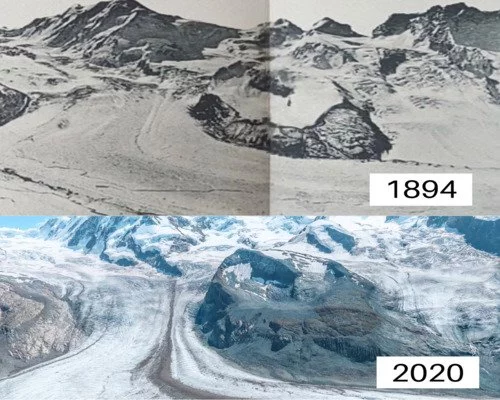

“Worldwide, mountain glaciers are in retreat because of global warming and this is causing impacts on mountain landforms, ecosystems and people. However, these impacts are highly variable. The latest report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) treats all mountains as equally sensitive and responding in the same way to climate change. However, this approach is not correct,” says Knight.

“Mountains with snow and ice work completely differently to low-latitude mountains where snow and ice are generally absent. This determines how they respond to climate and what future patterns of mountain landscape evolution we can expect.”

Mountain snow and ice globally provide water for hundreds of millions of people, but this water supply is under threat because of changing weather patterns and as mountain glaciers get smaller and smaller. In future, the water crisis in dry continental areas of Asia, North America, South America, and Europe will only get worse.

The research also shows how climate change will negatively impact on mountain landscapes and human activity. This includes an increased risk of hazards such as avalanches, river floods, landslides, debris flows, and lake outburst floods. These are made worse because of glacier retreat and permafrost warming. Alpine ecosystems and endemic species are already threatened with local extinction and mountain slopes are becoming greener as lowland forests spread to higher altitudes.

“As snow and ice shrink, mountain land surfaces are getting darker and this dramatically changes their heat balance, meaning they are warming up faster than the areas around them. Therefore, climate change impacts are bigger on mountains than they are anywhere else. This is a real problem, not just for mountains but also for the areas around them,” says Knight.

Mountain communities and cultures are also affected by climate change. Transhumance—moving livestock from one grazing ground to another in a seasonal cycle—and traditional agriculture are dying out as grazing areas shrink and as water becomes scarcer. Tourism, mining, urbanization, and commercial forestry are also pushing out these traditional practices. Mountain heritage landscapes and indigenous cultures and knowledge are not adequately studied or valued.

According to the new research, mountains should be viewed and protected as integrated biophysical and socioecological systems that include both people and physical landscapes. This could help protect these environments from future change.

“African mountains are vulnerable despite the lack of significant snow and ice. Our research on climate and landscape change, as well as human adaptations, in the Maloti-Drakensberg demonstrates how mountains and people are inextricably linked, and how both are threatened. Understanding these links can assist us in better protecting them from the worst effects of climate change” Knight says.