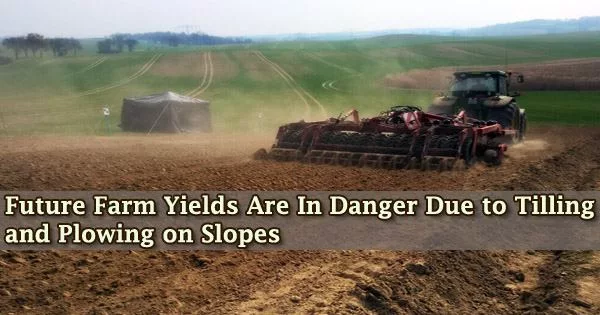

A recent study found that tilling and plowing on mountainous slopes thins farm soils and jeopardizes crop yields in the future.

Researchers from Lancaster University in the UK and Augsburg University in Germany contend that if farmers continue to till hill slopes, the soils on those slopes could eventually become so thin that the growth of food crops could be seriously affected.

Farmers have been tilling the soil in their fields to create seed beds so that they can grow crops for generations. The tilling procedure, which was formerly carried out using conventional animal-drawn ploughs, has changed to heavier, quicker tractors as farming has become more mechanized over the past century.

Plowing is a form of soil tilling that is known to transport a sizable amount of soil down slopes and contribute to climatic erosion. Tillage on sloped ground causes dirt to detach from the concave portions of hills and fall into valley bottoms.

Due to poorer nutrients, decreased biological activity, and decreased water storage, topsoil on slopes with thinned soils mixes with subsoil material, decreasing the quality of the soil’s ability to support plant growth.

Professor John Quinton, of Lancaster University and one of two Principal Investigators of the study, said:

“The role of tillage in reducing soil depth remains an under-recognised threat to plant production. While we have known that tillage moves significant amounts of soil down slopes, often exceeding the amount moved by water and wind erosion, we have known little about how the resulting thinning of the soils affects crop yields, until now.”

Professor Peter Fiener of University of Augsburg and second Principal Investigator said: “As machines continue to grow and climate change increases the frequency of droughts the impact of erosion of soils by tillage on crop production in rolling topography is likely to become more severe across many parts of the world.”

We show that the business as usual approach will depress crop yields in the long term. Farmers could look at mitigations such adapting tillage speeds depending on slope position and overall reducing tillage depths to slow the erosion process, but really farmers need to be looking at moving away from tilling on slopes to protect their soils and future yields.

Professor Peter Fiener

The Uckermark region in northern Germany, which is a highly mechanized and very productive agricultural region in Europe, was the location of the study for the wheat and maize crops.

Despite the fact that Uckermark has at least 1,000 years of agricultural production history, the researchers’ modeling indicates that over the next fifty years wheat and maize yields are projected to drop as modern mechanized agriculture speeds up slope-related erosion from ploughing.

The researchers used existing data on the impacts of crop thinning on crop yields in addition to soil redistribution and crop growth models to evaluate the effects of tillage at a regional landscape scale.

This allowed them to assess whether the production benefits in the landscape’s concave, soil-gaining regions balanced the losses brought on by soil-thinning on slopes.

According to their estimations, farmers in the Uckermark region will experience combined decreases in winter wheat yields of up to 7.1% within 50 years and up to 10% over a century if they continue to till on slopes in the same manner (in normal to dry years).

According to the study, maize yields could drop by up to 4% over 50 years and 5.9% over 100 years (in normal to dry years).

Because thinner soils are less able to retain rainfall and nutrients, their effects will be most noticeable during droughts. Over a period of 50 to 100 years, yields will also decrease in wetter years, albeit less dramatically than in normal and dry years.

Thousands of tonnes of food output from the Uckermark region alone will be lost as a result of these restrictions. According to the researchers, soil erosion-related crop production decreases are likely to occur anywhere tilling is done on slopes.

They contend that this anticipated rise emphasizes the necessity of taking immediate measures to lessen soil thinning brought on by tilling.

Professor Quinton said: “Our modelling shows that if we keep tilling our soils then we will see declines of crop yields at a regional scale this will be worse during periods of droughts as thinner soils are less able to retain water for plants.”

Professor Fiener said: “We show that the business as usual approach will depress crop yields in the long term. Farmers could look at mitigations such adapting tillage speeds depending on slope position and overall reducing tillage depths to slow the erosion process, but really farmers need to be looking at moving away from tilling on slopes to protect their soils and future yields.”

The pressure of tillage erosion will likely be increased if climate change increases the frequency of dry spells during crop growing seasons, according to the researchers, who did not model the consequences of climate change.

The paper’s authors are J Quinton of Lancaster University; JL Ottl and P Fiener of University Augsburg. John Quinton and Peter Fiener were joint principal investigators.