There is some evidence to suggest that fructose, a type of sugar found in many foods, may play a role in the development of Alzheimer’s disease. One study published in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease found that a diet high in fructose led to a reduction in insulin sensitivity and cognitive performance in rats. Insulin is important for regulating blood sugar levels, and insulin resistance is a risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease.

According to researchers at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, an ancient human foraging instinct fueled by fructose production in the brain may hold clues to the development and potential treatment of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). The study, which was recently published in The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, provides a new perspective on a fatal disease characterized by abnormal protein accumulations in the brain that gradually erode memory and cognition.

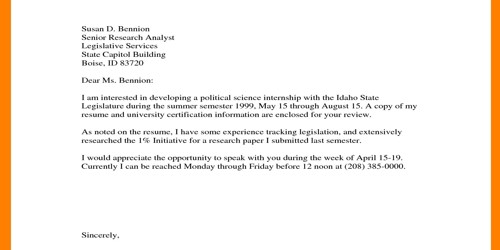

“We make the case that Alzheimer’s disease is caused by diet,” said the study’s lead author, Richard Johnson, MD, a renal disease and hypertension specialist at the University of Colorado School of Medicine. Maria Nagel, MD, research professor of neurology at the CU School of Medicine, is one of the study’s co-authors. According to Johnson and his colleagues, Alzheimer’s disease is a harmful adaptation of an evolutionary survival pathway used by animals and our distant ancestors during times of scarcity.

We believe that the fructose-dependent decrease in cerebral metabolism in these regions was initially reversible and intended to be beneficial. However, chronic and persistent reductions in cerebral metabolism caused by recurrent fructose metabolism result in progressive brain atrophy and neuron loss with all of the hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease.

Richard Johnson

“A basic tenet of life is to assure enough food, water, and oxygen for survival,” the study said. “Much attention has focused on the acute survival responses to hypoxia and starvation. However, nature has developed a clever way to protect animals before the crisis actually occurs.”

When faced with the prospect of starvation, early humans developed a survival strategy that sent them foraging for food. However, foraging is only effective if metabolism in various parts of the brain is inhibited. Foraging necessitates concentration, quick assessment, impulsivity, exploratory behavior, and risk taking. It is improved by obstructing anything that interferes with it, such as recent memories and attention to time. Fructose, a type of sugar, helps to calm these centers, allowing for greater concentration on food gathering.

In fact, the researchers discovered that the metabolism of fructose, whether consumed or produced in the body, was responsible for the entire foraging response. Metabolizing fructose and its byproduct, intracellular uric acid, was critical to both human and animal survival.

According to the researchers, fructose reduces blood flow to the cerebral cortex, which is involved in self-control, as well as the hippocampus and thalamus. Meanwhile, blood flow around the visual cortex associated with food reward increased. Everything triggered the foraging response.

“We believe that the fructose-dependent decrease in cerebral metabolism in these regions was initially reversible and intended to be beneficial,” Johnson said. “However, chronic and persistent reductions in cerebral metabolism caused by recurrent fructose metabolism result in progressive brain atrophy and neuron loss with all of the hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease.”

Johnson suspects the survival response, what he calls the `survival switch,’ that helped ancient humans get through periods of scarcity, is now stuck in the `on’ position in a time of relative abundance. This leads to the overeating of high fat, sugary and salty food prompting excess fructose production.

Johnson suspects that the proclivity of some Alzheimer’s patients to wander off is a relic of the ancient foraging response. More research on the role of fructose and uric acid metabolism in AD is needed, according to the study.

“We propose that dietary and pharmacologic trials to reduce fructose exposure or block fructose metabolism be conducted to determine whether there is potential benefit in the prevention, management, or treatment of this disease,” Johnson said.

Johnson suspects that the proclivity of some Alzheimer’s patients to wander off is a relic of the ancient foraging response. More research on the role of fructose and uric acid metabolism in AD is needed, according to the study.

“We propose that dietary and pharmacologic trials to reduce fructose exposure or block fructose metabolism be conducted to determine whether there is potential benefit in the prevention, management, or treatment of this disease,” Johnson said.