It has been discovered by a group of integrative biologists at the University of California, Berkeley, that variations in the pygmy zebra octopus’s striped pattern are distinct enough to identify them in long-term investigations. The scientists fostered 25 octopus hatchlings in their study, which was published in the open access journal PLOS ONE, in order to examine their striping.

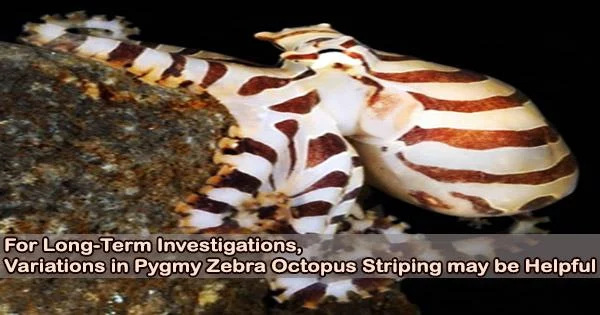

The pygmy zebra octopus (Octopus chierchiae), also known as the lesser Pacific striped octopus, resides in the waters off the West Coast of the U.S. and Central America. The octopus prefers the low intertidal zones and is easily identified by its zebra-like dark brown and white striped pattern. Hatchlings typically take between 250 to 300 days to mature.

The researchers in this new study stated that as the octopus has received minimal investigation, nothing is known about how it affects the environment. Additionally, they mention how little is known about their striping. They designed and executed a research of pygmy zebra octopus striping in their lab to correct that situation.

25 children were born as a result of a mating between an adult male and female that the researchers got. The children were then watched as they matured, with an emphasis on their striped patterns.

The research team found that the stripes began to appear at about two weeks. After four weeks, they appeared to be firmly set. They appeared to be solidly established after four weeks. They also observed that the pygmy zebra, like other octopus species, has a propensity to alter its appearance, including color, in response to disturbance.

In order to analyze the specimens’ persistent striping patterns, they had to come up with a way to film and take pictures of them without disturbing them.

The research team discovered that each individual’s striping patterns were incredibly distinctive, much more so than a person’s fingerprint. Additionally, they noted that participants studying images were able to correctly identify specimens with an accuracy rate of 84.2%, indicating that the changes were robust enough to be easily detectable.

According to the group, this indicates that the striping effect is potent enough to permit long-term research on individuals in the wild without the use of tags.