Crime and delinquency rates fluctuate greatly with age, reaching a peak around the age of 15, then sharply declining by the mid- to late-20s. Most young people migrate from middle school to high school, usually in a new area, as their engagement in delinquency increases.

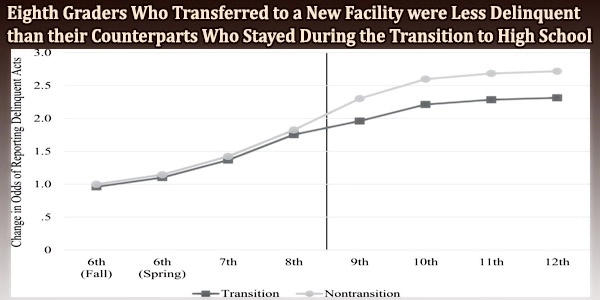

A recent research of middle and high school students looked at how switching high schools between the eighth and ninth grades affects juvenile delinquency, as opposed to staying in the same facility throughout this time. According to the study, children who transferred to a new school reported much less delinquency than those who did not.

The study, by researchers at Randolph-Macon College, Pennsylvania State University, and Northeastern University, appears in Criminology.

“Our findings highlight the role of a crucial yet understudied life transition in shaping adolescent delinquency,” notes Brittany N. Freelin, assistant professor of criminology at Randolph-Macon College, who led the study. “They also underscore the potential of changing social context to reduce juvenile delinquency in high school.”

Important life transitions, such as starting to date, having a parent go to jail, and joining a gang, shape young people’s participation in crime. Most (12,000 of 13,800) U.S. public schools move students to new high school buildings after middle school. Although the transition from middle to high school is crucial, there hasn’t been much research on how this significant transformation affects adolescent crime.

More than 14,000 mainly White students who participated in the Promoting School-Community Partnerships to Enhance Resilience (PROSPER) study were studied in a quasi-experiment. All districts were in rural communities or small towns in Pennsylvania or Iowa.

More than 700,000 adolescents in the United States are arrested every year for delinquent offenses, such as stealing, fighting, and property damage. A key implication of our findings is that middle school students who have already been identified as offenders might be better off changing school settings than remaining in the same social and academic environment.

Cassie McMillan

To be eligible, districts had to enroll 1,300 to 5,200 students, with at least 15% eligible for free or reduced-price lunch. In sixth through seventh grade, a substance addiction prevention program with school and community-based components was randomly assigned to half of the districts.

In order to determine a student’s delinquency, the study took into account their responses to 12 survey questions about their involvement in criminal activity over the previous year. These questions asked about theft, assault, property damage or destruction, breaking into a building, throwing objects to harm or frighten people, running away from home, skipping school, and shoplifting.

Researchers were able to directly compare students who switched schools after eighth grade with those who stayed at the same school because they tracked kids over eight waves from sixth through 12th grade. Twenty-two of the districts transitioned students to a new high school; the four districts that did not move students to new buildings for high school served as controls.

Students who transitioned between schools reported significantly less delinquency after the shift than those who did not, and this difference persisted through 10th grade. The decline in delinquency was most pronounced when adolescents from several middle schools moved to a single high school (i.e., multifeeder transitions).

Students who transitioned to a new school had fewer delinquent friends and participated in less unstructured socializing following the change in school environment, which partially mediated their reduced delinquency.

“More than 700,000 adolescents in the United States are arrested every year for delinquent offenses, such as stealing, fighting, and property damage,” explains Cassie McMillan, assistant professor of sociology, criminology, and criminal justice at Northeastern University, who coauthored the study. “A key implication of our findings is that middle school students who have already been identified as offenders might be better off changing school settings than remaining in the same social and academic environment.”

The change to a new academic environment may be a “shock” to an adolescent’s social milieu, which may eventually lead to a decline in juvenile delinquency, according to the authors. Additionally, they make the case that it could be advantageous to make it easier for children to make friends and participate in organized extracurricular activities as they get acclimated to a new school.

The study’s authors note that the school districts they examined are not nationally representative (e.g., they do not include large urban communities and concentrated minority populations).

But while their findings may not generalize to other settings, they point out that residents of the districts studied have relatively limited school choice, which reduces the chance that the effects of transitions are the result of individual-level selection.

In addition, while the study considered many behaviors, high school transitions likely shape additional risky behaviors that were not examined (e.g., smoking, drinking, other types of substance use).