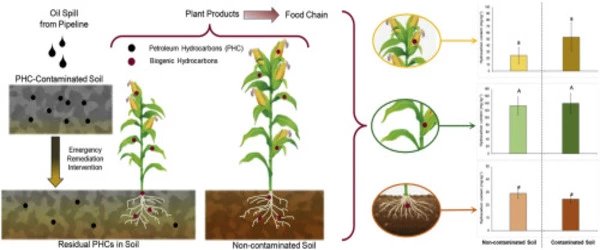

Plant remediation, also known as phytoremediation, is a technique for mitigating and cleaning up contamination in soil, water, and air. When it comes to petroleum contamination, phytoremediation can be a successful and environmentally friendly solution.

Initial fertilization and grass seeding decisions may have a long-term impact on how plants and their associated microbes break down pollution in petroleum-contaminated soils, according to a research team led by a University of Alaska Fairbanks professor.

Mary Beth Leigh, a microbiology professor, and her colleagues discovered that planting grasses or adding fertilizer, or a combination of the two, to a contaminated site had surprisingly long-lasting effects on the microbes associated with local vegetation.

The study, which was recently published in the journal Microbiology Spectrum, suggests that initial phytoremediation strategies – the use of plants to restore polluted environments – should be prioritized even more. The study is based on previous research conducted by the US Army Corps of Engineers in a petroleum-contaminated area near Fairbanks, Alaska.

Providing communities with the best advice on how to mitigate contamination in an affordable way, such as by using local plants and their associated microbes, has the potential to significantly empower Alaska Native communities in remote areas whose ecosystems are threatened by petroleum pollution.

Mary Beth Leigh

The previous study began in 1995 when scientists established test plots of petroleum-contaminated soil. They planted grass on some plots. On others, they amended the soil with fertilizer. Some plots received both grass and fertilizer, while others received neither.

After the initial three-year study, the site was no longer monitored, but the UAF team returned in 2011 to assess long-term progress. The contamination was no longer detectable at that point, and native species such as white spruce, fireweed, yarrow, willow, blue grass, poplar, buffalo berry, birch, and clover had replaced the originally planted grasses.

Three years later, the team took additional samples to test for microbes in each plot. Unexpectedly, the team found that the microbes varied from plot to plot depending on the initial mix of fertilizer and grass, rather than on the types of native species that had moved in.

Since microbes, rather than plants, are responsible for breaking down petroleum, these differences could improve the phytoremediation process. With further study, scientists could strategize ways to make phytoremediation more effective by using plant and fertilizer combinations that encourage petroleum-biodegrading microbes to thrive.

‘From the start, the jury is out on which plant and fertilizer treatments would be the most effective,’ Leigh said. ‘That is something we are testing in another long-term monitoring site as part of a project.’

According to Leigh, crude oil and diesel pollution frequently endanger ecosystems in rural subarctic areas.

‘Phytoremediation could be an important tool in the toolbox of rural communities that experience diesel fuel soil contamination,’ said Leigh, who works at the University of Alaska Institute of Arctic Biology. ‘Providing communities with the best advice on how to mitigate contamination in an affordable way, such as by using local plants and their associated microbes, has the potential to significantly empower Alaska Native communities in remote areas whose ecosystems are threatened by petroleum pollution,’ says the report.

The chemical analysis for the study was compiled by Rodney Guritz, a former student of Leigh’s and the owner and principal chemist of Arctic Data Services. Guritz believes that the new findings have the potential for industrial applications.

‘In light of climate change, we urgently need to shift away from dig, haul, and burn, and I see phytoremediation as a critical component of this necessary shift,’ he said.