Introduction

In the last fifteen years there has been a rapid increase in the activity of foreign banks in

several developing economies. Although, foreign bank entry occurred in many developing countries,

its pattern was not uniform (IMF 2000). In Latin America as well as in the Central European (CE)

countries, the share of foreign banks in the first half of the 1990’s was well below 20 per cent and a

decade later the foreign banks controlled almost 75 per cent of total banking assets. By contrast, in

East Asia over the same period, the average share rose only from 3 to 7 per cent (Barth 2001). The

level of development of a country seems also not to be an obvious determinant explaining foreign

bank entries. In such countries as Egypt or Bangladesh, the foreign banks hold less than 10 per cent

of banking assets; on the other hand in Cambodgia, Czech Republic or Turkey more than 60 per cent

is in the foreign hands. The differences are also meaningful among the transition countries. In

Azerbaijan or Uzbekistan, the share of foreign banks is less than 5 per cent, whereas in such

countries as Hungary or Lithuania it amounts to almost 100 per cent. The discrepancies are also in

the developed countries. In Germany or United States, the foreign-controlled banks hold less than 10

per cent of assets, whereas in Luxemburg or New Zealand they hold more than 90 per cent.

A good financial system has been shown to be an essential ingredient for sustainable

economic growth (Levine 2005, World Bank 2001). The literature on foreign banking has also

shown that foreign bank participation can help develop a more efficient and robust financial system

(Claessens et al. 2001). Most evidences show that increased foreign banking is generally positively

correlated with the improvement of the efficiency of the domestic banking sectors and helps

strengthen countries’ financial systems. Especially, studies on the developing countries have shown

that these countries have benefited from this trend at most.1 Therefore, from the policy perspectives

it is important to know what determines a favourable environment that encourages cross-border

activity and entering foreign banks. Despite the recent trends in the banking internationalization, 28

per cent of developing countries still have foreign bank participation below 10 per cent and 60 per

cent of developing countries have below 50 per cent. Among these developing countries with the

foreign bank assets below 10 per cent, the transition countries constitute almost 20 per cent and 25

per cent of the sample with the foreign bank participation below 50 per cent (Van Horen 2006 and

EBRD). As the experience of some Central and Eastern European (CEE) transition countries has

shown the foreign bank participation has turned out to be inevitable to build stable and efficient

financial system. Hence, we would expect that in other developing and transition countries, the

entering the foreign banks might also turn out to be necessary in the near future.

At the same time, by permitting foreign banks to enter, the policy makers should take care

about how the foreign banks operate in the host markets. First, letting the foreign banks come in, the

host countries may open themselves up to economic fluctuations in the entrants’ home countries.

Moreover, the organizational form may affect the competitive structure of the local banking systems,

threatening profits and market share of domestic banks and affecting the price and quality of banking

services in the host country. And finally, the entry through de novo operation involves different

levels of parent bank responsibility and financial support. This can have implications not only for

parent bank but also for local regulators, who care about the stability of the host country, and for

local depositors who care about the safety of the savings. The recent experience of Argentina, where

some foreign banks decided not to recapitalize their foreign subsidiaries presents the best example

on this.

On the other hand, the literature on international banking comes up with some arguments in

favour of one entry mode versus another. While the empirical studies show that the entry of foreign

banks through cross-border mergers and acquisitions is positively correlated with the efficiency

improvements of the acquired banks, the entry of foreign banks through subsidiaries may promote

greater access to the financial services in the host countries, as in many countries, the foreign

subsidiaries have powers identical to those of domestic banks. Hence, although, the trade-off

between one entry mode versus another is by local regulators required, from the policy perspectives,

it is also important to know what determines a foreign bank’s choice of organizational form.

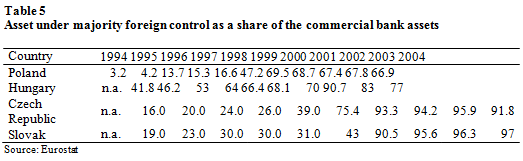

Today, the banking sectors of most transition countries are among the ones with the highest

share of foreign-controlled banking asset in the world. It ranges from 70 per cent in Poland to almost

100 per cent in Slovakia (Allen et al. 2006). The change in the share of foreign participation in

banking in these countries from the early transition years to the later ones is significant.

The pattern of the banking internationalization was also not uniform in these countries. At the

beginning of the transformation, foreign banks entered the region mainly as de novo operation.

Encouraged by the fast going economical and political reforms in the region and high economic

growth, the pressure to enter the CE region has increased. With the intention of gaining rapidly share

in the local market most foreign banks used mergers and acquisitions’ (M&As) entry mode instead

of de novo operation abroad.

Generally, banks are found to be attracted to markets abroad to exploit favourable financial

system environment and to take advantage of economic opportunities in those countries (Goldberg

and Saunders, 1981). However, the question arises, what the foreign bank managements saw in the

CE countries that in the middle of the 1990s experienced in an increase of foreign bank’s entrance?

Do the theorists from the developed countries find the acceptation of their thesis in the countries

characterizing negative real economic growth, high inflation, uncertainty with the political

institution and an underdeveloped banking sector? In this paper, we try to analyze the determinants

which in the light of high uncertainties in four countries: Poland, Czech Republic, Slovakia and

Hungary, contributed to the foreign bank entries into these markets.

Our decision on the choice of this sample has been driven by some variations between these

countries. On the one hand, these countries have experienced the most significant pattern of banking

internationalization among almost all transition countries; on the other hand, they represented

various policies toward foreign bank entries as well as started their transition processes with

different initial conditions. For this reason, in our opinion, these countries constitute the best testing

ground on determinants of foreign banking participation and entry modes chosen by foreign banks.

The literature comes up with various motives for foreign banks to go abroad. In addition, the

mode of entry or the organizational form chosen by foreign banks is not only an issue of their

strategy or mission, but also depends on the entry country’s conditions and environment. Despite the

profound changes in the banking sectors of the CE economies as well as growing number of

countries embracing foreign bank entries, there is still open debate about the determinants of

banking internationalization and its modes of entries. The empirical evidences presented in the

literature come mostly from the US and developed European countries. There has been little

empirical research in this field for the developing countries so far. With our study we present the

empirical evidence on the motivation and entry vehicles of foreign banks in the CE markets.

Our contribution with respect to previous literature is twofold. First, we consider a new and

wider set of explanatory variables than previous studies, verifying different hypothesis and relative

importance of economic factors in determining banks’ choice of whether and where to expand

abroad. Second, we use a unique sample of entry models of foreign banks entering the region. Our

framework permits us to examine the relation between the relative importance of the different

country’s factors and the chosen entry model by foreign banks in the CE region.

Our major finding is that the most important factors determining foreign bank entry into CE

countries were development of the financial system and the banking sector as well as the legal origin

of the home country. We also show that most of the entries occurred in the period of a poor creditor

rights protection. Furthermore, our results find that the size of economic growth rates differentials

between host and home markets, and finally the distance between the host country and the banking

headquarters were of great economic importance. We also show that determinants of bank

internationalization have changed within development of the financial systems. Finally, our findings

present that the economic determinants had also an impact on the decision of organization form of

the foreign banks in the CE local banking markets.

The remaining of the paper is organized as follows. In the next section we present a short

overview of problems encountered by the transition from planned economy to the market economy

in the four CE countries. The third section presents the literature review about determinants related

to our main hypothesis of the banks’ expansion abroad. At the end of this section we present also the

results of the few empirical papers on foreign banking in the transition countries. In the next section,

we present the variables based on previous empirical research, which we have applied in our

regressions. In a subsection we develop also our main hypothesis related to the economic

determinants and the decision about the entry mode of the foreign banks into the CE local banking

markets. In the fifth section we present the model which investigates the incentives of foreign banks

for entering CE countries in the last decade, the period of enormous uncertainties and economic

transformation. The next section describes the results and compares them with other ones from

developed countries. Finally, the last section of the paper concludes.

2. Banking sector in early transition process

All the CE countries in our study followed the socialist financial system model, which was

designed to support the central planning economic system. Despite the centralization of financial

functions the state directed credit allocation with scant regard for repayment capacity, using the

national bank and state banks to channel funds to state owned enterprises

As a consequence of political changes in the year 1989 the creation of an effective financial

was a priority for the new governments in the CE countries. The aim was to implement a market-

oriented economy and thus fundamental changes were needed in the financial system. So the

banking industry was one of the first economic sectors, which underwent a fundamental

transformation.

Hungary was the leader among the CE countries in the banking reforms. The government began the

banking reforms even before the political changes. In the early 1980s the Hungarian government

permitted a number of foreign banks to set up operations, even though these banks competed with

state-owned banks in the areas of foreign exchange and trade-related transactions. The centralized

mono-banking system was replaced by a two-tier banking system as National Bank of Hungary

assumed the role of central bank in 1987. The new central bank was charged with pursuing monetary

policy, including exchange rate policy, and was made responsible for the supervision of the banking

sector. The second tier consisted of the specialty banks, newly created commercial banks, and the

few already operating foreign banks (Hasan and Marton 2003).

In Poland the reform of the banking system started in 1987, when the government allowed for

creation of the joint-stock banks, yet they were still owned by the state. Two years later a new

banking law was introduced, which created a two-tier banking system in Poland.

In all the CE countries as a process of creating a two-tier banking system the commercial and retail

operation was divested from the activity of national banks and transferred to new commercial banks.

In Hungary the government set up three new state-owned banks from the National Bank of Hungary,

in Poland nine banks were created out of the National Bank of Poland, while in the Czechoslovakia

through divestment form the State Bank of Czechoslovakia four banks were established. These

medium sized state-owned banks inherited segments of the old network and staff of the national

banks, household deposits and loan portfolio comprising mainly of credits granted to the state

enterprises of unknown quality. They supplemented the already existing large state-owned specialty

banks. Those specialty banks existed separately from the central bank and performed specific

functions on behalf of the government in the planned economies. A state savings bank with an

extensive branch network was responsible for collecting household deposits, although most savings

was forced and done by the state. A foreign trade bank handled all transactions involving foreign

currency. An agricultural bank provided short-term financing to the agricultural sector. A

construction bank funded long-term capital projects and infrastructure development (Bonin and

Wachtel 2003)3.

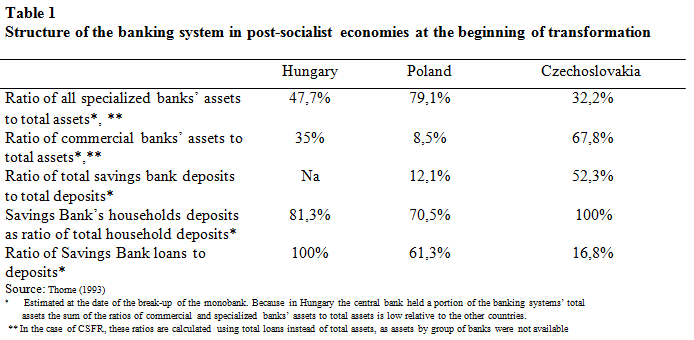

Table 1 presents the representatives of each specialization group in a particular

country.

Although three to nine new state-owned banks were set up through the divestment from

central banks, yet the banking industry remained fragmented as the three to four specialist banks still

dominated the emerging banking system. However, already in the first year of the transformation,

new banks started to operate in transition countries. The entry requirements policy of the newly

central banks and the licensing procedure for the de novo banks was very lenient at that time. The

principal motivation was to increase the competition of the four large banks, which were considered

too inertial and ineffective. The number of de novo banks was very impressive at this time. In

Hungary six new banks were established, in Poland 20 new banks and 13 new banks in

Czechoslovakia in 1990. Of these, three were foreign owned in Hungary, five in Poland and four in

Czechoslovakia.

However, this huge expansion in de novo domestic private banks later caused serious problems for

the financial system. Most of those domestic banks were in general undercapitalized and placed an

additional unwanted burden on an underdeveloped regulatory structure. In addition, some of them

have been set up either by state enterprises or by local governments in order to provide soft lending

to them. Hence, the features of banking system at the beginning of transformation were structural

segmentation, high concentration of the assets caused by few large and medium sized state-owned

banks, and an increasing number of small domestic private banks (Bonin, Hasan and Wachtel 2005).

Given the poor banking supervisory environment caused by poor accounting and financial

information, weak off-side surveillance capacity and the lack of experience with on-site

examinations, it was bound to lead to problems in the banking industry. The benevolent licensing

policy, combined with inexperienced and still weak banking supervision, caused the new private

domestic banks to take on rather unsound development strategies. In addition, the absence of

effective legal and institutional supervision also invited fraudulent behaviour by the managements of

these banks. As a consequence the new domestic banks started to have liquidity problem in very

short term. Also the former specialist banks get into trouble as they inherited a loan portfolio from

the past in which credit was granted not on commercial terms. In addition, those banks were still the

primary lending vehicle and quasi fiscal financing, usually for loss-making state-owned enterprises

that had to be either privatized or closed. The number of non-performing loans increased

significantly as the structural problems of the real economy increased caused by the ongoing

transition process in CE countries (Bonin and Wachtel 2003). Once the compliance of supervision

provision requirement was enforced, the quality of loan portfolios became apparent. As a

consequence several large state-owned banks reported huge losses and the equity adequacy ratios

were below the requirement of the banking supervision.

In Hungary, at the end of 1992, 15–28 per cent of the credits extended were nonperforming

loans and were primarily borrowed by the state-owned enterprises during the pre-1989 era (Hasan

and Marton 2003). The situation quickly became unsustainable as failing financial institutions turned

for bailout to the National Bank of Hungary. As a result the newly established national bank was in

jeopardy and the Hungarian government had to step in through a series of costly loan consolidation

programs beginning in 1992 (Várhegyi 1994, 1995, Balassa 1996). The government objective of the

bailout programs was the cleaning-up of the books of the state-owned banks, which would permit a

sell of to foreign strategic investors. The cost of the program approached close to 10 per cent of

Hungary’s GDP.

Poland was the most successful in dealing with the bad debt crisis. The success is attributable to the

design of the recapitalization program, which provided the least incentive for moral hazard. In

addition, the central bank encouraged the buyout of troubled banks by foreign strategic investors. As

a consequence, the costs of bad debt bank crisis were below 1.5 per cent of GDP and were the lowest

among the transition economies.

In Czechoslovakian a Consolidation Bank was established as a vehicle for the takeover of the

accumulated bad loans till 1991. The bank was created to take nonperforming loans from the balance

sheets of the largest state-owned banks, and the clean-up of the books of other banks in the periods

both before and after the division of Czechoslovakia (Dědek, 2001). The overall costs of the

Consolidation Bank are estimated to have reached more than 7 per cent of GDP. Nevertheless the

creation of the Consolidation Bank did not solve the problem of the banking sector and the Czech

National Bank had to intervene in the affairs of eight banks by 1996. In 1997 classified credits

reached already 32 per cent of the total banking credits in Czech Republic (Dědek, 2001). Finally the

problem was resolved through a postponed privatization of the largest banks. However, the estimates

indicate that the final cost of bank bailout in the Czech Republic may have approached 30 per cent of

GDP as compared to just 1.5 per cent in Poland or 10 per cent in Hungary.

The growing problem of bad debt was the tiger for the postponed bank privatization in all the

transition countries. In most of these countries the privatization of state-owned banks started in the

beginning of the 1990’s, yet foreign banks were entitled only to minority shares whereas controlling

stakes remained with the state treasury. However, as the problem of bad debt increased, the

government was more likely to sell controlling shares in the state owned banks to foreign strategic

investors. The governments in transition countries were in addition encouraged by privatizations

revenues as they started with the privatization of state owned banks. Thus, at the end foreign bank

made their entrance into transition countries mainly through rescuing the ailing domestic banking

sector.

In opposition to the other transition countries, in Hungary bank privatization policy from the

beginning of was aimed at selling controlling shares in state-owned banks to foreign investors.

Although the privatization required prior an initial recapitalization of the banks so that the

combination of current net worth and franchise value would attract a foreign investor. As a

consequence the Hungarian government engaged in multiple recapitalizations of its domestic banks

caused by the poor quality of loan portfolios. Thus, the government was able to attract foreign

investors and thus signal credibly the end to bailouts of these banks (Hasan and Marton 2003). At the

end of 1997, four of Hungary’s five large state-owned banks had been sold to foreign owners and by

the end 2006 the share of foreign banks was 63 per cent of total assets.

The Polish experience indicates the danger in combining the resolution of bad loans with

bank responsibility for enterprise restructuring. The main instrument used to restructure bad loans

was debt to equity swaps. Hence, weak banks with no expertise in restructuring large companies

ended up taking ownership stakes in their weak clients. Therefore bank credit was provided regularly

to ailing enterprises and no meaningful enterprise restructuring was promoted banks (Gray and Holle

1996). Poland’s program strengthened, rather than cut off the ties between weak banks and their

undesirable clients and, thus, postponed painful restructuring of ailing enterprises (Bonin and Leven

2001).

In addition, in Poland the government presented an inconsistent policy toward foreign banks. In

1993 the government attracted the first strategic foreign investor for two of the nine midsized

commercial banks, yet only minority shareholding was allowed. Thus, foreign institutions controlled

only 2.1 per cent of Polish banking assets at the end of 1994. The National Bank of Poland however

enabled foreign bank entry at the beginning as de novo operation and later through either the buyout

of failing banks or their nonperforming credit portfolio. At the same time the government arranged a

large bank merger, in which the three of the nine midsized commercial banks were merged with one

of the state savings bank to form the second largest financial group in Poland. However, the

persisting inefficiency of Polish banking system caused the government to change their attitude

toward foreign investors. So in 1997 foreign bank were allowed to take control in the initial

privatization of the state-owned banks. Since then significant strides have been made and foreign

strategic investors took control in some of the largest commercial banks. In 2004 the government

sold 30 per cent of shares in the country’s largest retail bank PKO BP through the Warsaw Stock

Exchange. It was the last state-owned commercial bank and therefore the government decided to

retain a majority stake in it. Yet, at the end of 2006, 75 per cent of total bank assets were controlled

by foreign capital.

In the Czech Republic bank privatization took place twice. In 1992 the government of the

Czechoslovakia conducted a voucher privatization transferring the shares to individual investors and

investment funds in exchange for vouchers. Three of the four large commercial banks participated in

voucher privatization, yet these banks participated on both sides of privatization as they also

sponsored the largest investment funds. As a result, Czech banks took ownership stakes in their

voucher-privatized clients, some of which continued to be loss making, while the state retained a

controlling ownership stake in the large banks. Consequently, voucher privatization in the Czech

Republic strengthened the relationship between banks and clients and left bank governance held

hostage to the legacies of the past. Thus, the privatization of the Czech banks was to little avail

because soft lending practices continued. As a consequence these banks accumulated bad debts,

which have been later transferred to the Consolidation Bank.

In Czech Republic the second round of privatization occurred from 1998 to 2001, when the

government sold holding in three major banks. Until than no Czech bank was sold to a foreign

investor. Those three banks accounted for 38 per cent of assets. Since then the proportion of foreign

owned bank assets soared to 96 per cent in 2006.

All these four transition countries took place in the enlargement process of the EU and are

members of the EU since May, 2004. Consequently they had to adapt the Second European Banking

Directive and the Single European Passport, which eliminated the last market-entry barriers into

their banking sector. Although in all the countries the deregulation of the banking sector could be

observed since 1997.

Concluding, the increasing foreign bank presence since the 1990s is one of the most striking

developments in the banking system in the transition economies. On average, foreign-owned banks

account for more two thirds of total bank assets in most transition economies at the end of 2006. The

percentage of assets in banks with majority foreign ownership in these countries ranges from 22 per

cent in Slovenia to 99 per cent in Estonia. By contrast, in EU-15, only Luxemburg and Great Britain

had more than 50 per cent of its banking sector controlled by foreign interests in 2005 (Allen,

Bartilloro and Kowalewski, 2006). Thus, banking sectors in transition countries differ significantly

from their counterparts in developing as well as from emerging market countries by the unusual high

percentage of assets held by foreign banks.

3. Literature Review

In the last decades various studies have been conducted that investigated the motivation and

location choice of banks abroad4.

The classical hypothesis (Aliber, 1984) is that banks follow their customers abroad, being

afraid of losing them once they have established relationships with banks operating in other

countries. According to the defensive expansion hypothesis, banks’ expansion enables them to retain

information on their customers.

Multinational banking hypotheses relating to the servicing and following their clients generally find

empirical support. Nigh et al. (1986) presented in their study of US banks’ overseas expansion that

the major determinant was to respond to the financial needs of US firms abroad. Their study implies

that US banks do not lead, but follow the US business sectors. Goldberg and Saunders (1980)

analyzed the factors affecting the expansion of US banks into UK, concluding that US trade is

significantly conducive to the growth of US banks in UK, while the Eurodollar interest rate and the

exchange rate are not significant factors. In a later study Goldberg and Saunders (1981) examine on

the contrary the growth of foreign banks in the US. They results provided evidence that the direct

investment made by foreign firms into the market was a significant positive determinant of growth

of foreign banks’ market share in the US. Hultman and McGee (1989) and Grosse and Goldberg

(1991) also provided results that foreign banks entered the US market to service the international

trade and direct investment needs of their home-country clients. In a recent study similar results were

presented by Magri et al. (2005) in a study on entry decisions and activity levels of foreign banks

operating in Italy. The authors report that trade influences both entry decision and activity levels of

foreign banks. However, they found also that the relative profitability of banking activity in Italy

strongly influences both entry decisions and activity levels. As a consequence the observed

correlation in several studies between proxies for foreign investment trade and the structure of a

foreign market complicates the conclusions on motivation. Thus, the motivation of bank to move

abroad may be explained by the need to follow its clients and equally by the lure of a potentially

significant new market.

The importance of new market opportunities in attracting foreign banks has been emphasized

by the eclectic theory of direct investment (Dunning, 1977). The theory was extended by Gray

(1981) to explain multinational banking. In this theory multinatinalization of banks is contingent

upon location-specific factors and ownership-specific factors.

The location-specific factors are the size and competition in the foreign market, presence of entry

restriction and other regulations. Foreign market size has been found to be a significant driver of

multinational banking by Terrell (1979) and Goldberg and Grosse (1994). While, Goldberg and

Johnson (1990) provides some support for relative lack of competition or high relative profitability

as causal factors. In contrast Nigh, Cho and Krishnan (1986) did not found that local market

opportunity to have a significant effect. In their study they analyzed the role of location-specific

factors in foreign involvement of the US banks.

Recent studies presented a new approach to multinational banking and market structures. In those

studies banks may use economic crises and distortions in the banking industry in order to enter a

foreign market. Peek and Rosengren (2000) found evidence that as a result of liberalizations and of

the worsening conditions in domestic markets, foreign banks expanded in several Latin American

countries. Consistent with this result Guille´n and Tschoegl (2000) found that Spanish banks have

increased their ownership in Argentina’s banks during the economic crisis of the last decade.

However, Engwall et al. (2001) found that foreign banks lost market share in Sweden during the

Scandinavian banking crisis there in the early 1990s. On the other hand, at the same time they found

that foreign banks increased their market share in Norway. As we see the empirical results do not

present a clear picture on market structure, yet it seems that foreign banks may use a domestic crisis

in order to increase their market share in the market.

The ownership-specific factors emphasis that banks become multinational in order to employ their

domestic strengths in foreign markets at low marginal cost and thus leverage those strengths. Such

advantages can take many forms, including large scale of operation, low cost of capital, unique

business processes or banking technology, skilled personnel and banks’ reputation (Nigh 1986;

Tschoegl 1987). Among bank-specific characteristics, size has been found to affect mainly the

patterns of foreign direct investment. Ball and Tschoegl (1982) provided evidence that the larger

banks are much more international than smaller ones.

Consistent with this result Focarelli and Pozzolo (2001) have shown that banks with foreign

shareholdings are on average larger and have headquarters in countries with a more developed and

efficient banking market. However, Berger et al. (1995) argue that larger banks have generally larger

and more internationally diversified customers, and therefore these banks have more incentives to

follow their clients when they operate abroad. If it is the case than large foreign banks would rather

follow their multinational clients than have been encouraged by their comparative advantage. In

addition, several studies have documented that foreign owned banks are not as profitable as their

domestic peers. Seth (1992) and Nolle (1995) found that foreign owned banks were not as profitable

as domestically owned banks, based on aggregate profits. DeYoung and Nolle (1996) use a profit-

efficiency model and conclude that foreign-owned banks were less profit-efficient because of their

reliance on purchased funds. Molyneux et al. (1997) applying a simultaneous equations framework

concludes that the profitability of foreign owned banks was mainly related to capital ratios,

commercial and industrial loan growth and asset portfolio composition.

Although, the presence of higher demand profit opportunities in the market of destination of the

investment seems likely to be an obvious determinant of the location choice of multinational banks,

the empirical studies are more equivocal on location-specific factors and ownership-specific factors

as motives for banks to go abroad.

Apart from leveraging existing advantages, following clients or seeking attractive markets

overseas, there are other determinants of bank expansion abroad. In the opinion of Focarelli and

Pozzolo (2001) bank internationalization depends on other factors besides the degree of economic

integration among countries. As an example Claessens et al. (2000) analyze foreign presence across

80 countries from 1988-95, and find that foreign banks are attracted to markets with low taxes and a

high per capita income. Although, the regulatory restrictions have been found to significantly affect

the pattern of bank investment abroad. Miller and Parkhe (1998) presented that US banks prefer to

expand in countries where capital requirements are less stringent and taxes are lower. Consistent

with this result, Nigh et al. (1986) and Goldberg and Johnson (1990) present that restrictions on the

entry of foreign investors significantly reduce the degree of internationalization of a country’s

banking market. According to Boot (1999) governments may wish to have the largest banks in their

countries to be domestically owned. Thus, we would expect that in high concentrated markets as the

CE are, the entry of foreign banks is more difficult. In this case a single acquisition of the former

state owned banks would imply the loss of a significant market share to the advantage of foreign

financial institution.

The literature on the restructuring and development of the financial sector in transition

economies is abundant. However, the empirical literature on banking in transition countries

concentrates mainly on the impact of foreign bank entry on banking efficiency. Yildirim and

Philippatos (2002) find that foreign banks in transition countries are more cost efficient but less

profit efficient relative to domestic banks. Hasan and Marton (2003) and Fries and Taci (2003)

demonstrate that the entry of more efficient foreign banks creates an environment that forces the

entire banking system in transition countries to become more efficient, both directly and indirectly.

Buch (2000) compares interest rate spreads in Hungary, Poland and the Czech Republic from 1995

to 1999. She finds evidence confirming the hypothesis that foreign banks create a more competitive

market environment in transition economies, but only after they have attained sufficient aggregate

market share. The results were conformed to Zajc (2002), who reported for six European transition

countries that foreign bank entry reduces net interest income and profit, and increases costs of

domestic banks. While, Bonin et al. (2003) examine the performance of banks in eleven transition

countries and show that majority foreign ownership is associated with improved bank efficiency.

On the contrary, Green et al. (2002) estimate the efficiency of domestic and foreign banks in Central

and Eastern Europe (CEE) in terms of economies of scale and scope. They find that foreign banks

are not really different from domestic banks and that bank ownership is not an important factor in

reducing bank costs. There results were in oppostition to Claessens et al. (2001), who reported that

foreign banks in CEE countries tend to have lower overhead costs and loan loss provisions and

higher profits than domestic banks.

Fries and Taci (2005) presented that costs are lower in those transition countries where foreign

owned banks have a large share of assets. While, de Hass and van Lelyveld (2003) argued that the

increase in foreign banks have contributed to credit stability in CEE by keeping up credit supply

during crisis periods, while domestic banks reduced theirs. Although their results also show that the

privatisation of domestic banking systems in CEE as such has not led to immediate positive stability

effects. They have shown that banks that are sold to foreign strategic investors do not change

immediately into more efficient banks. Additionally, they presented that the country conditions

matter for foreign bank growth, as they have reported a significant negative relationship between

home country economic growth and host country credit by foreign bank subsidiaries. Related results

were provided by Bonin et al. (2005) in a study on the impact of bank privatization in transition

countries. They have reported that state-owned banks are the least efficient and foreign de novo

banks are the most efficient of all bank types in transition countries. However, they found also that

domestic banks have a local advantage against foreign banks in pursuing fee for service business.

The effects of foreign ownership on bank efficiency have been also examined in a few

country specific studies. For Hungary, Hasan and Marton (2003) find that relatively more efficient

foreign banks created an environment that forced the entire banking system to become more efficient

in the years 1993 to 1998. Nikiel and Opiela (2002) find that foreign banks servicing foreigners and

business customers are more cost-efficient but less profit-efficient than other banks in Poland from

1997 to 2000. For Czech Republic and Poland, Weill (2003) reported that foreign owned banks were

significantly more efficient than domestically owned banks in 1997. On contrary, Matousek and Taci

(2002) observed greater efficiency in private banks in the Czech Republic for the period 1993–1998,

yet they did not found any evidence of greater efficiency of foreign owned banks in their study.

Although these single country studies provide mainly a positive relation between foreign ownership

and bank performance, yet the results are not always convincing.

Finally, Naaborg et al. (2003) present that the three largest banks in most European transition

economy are in foreign hands. However, banks from non-European countries are almost absent in

the transition countries. In addition, they report that there is a relatively strong presence in some of

the European transition economies of foreign banks from neighbouring countries.

While the empirical evidence confirms the follower relationship hypothesis, the importance

of local market opportunities requires deeper investigation. So far little research has been undertaken

in order to examine the relation between foreign bank expansion and economic and structural

characteristics of host countries. In particular, a variable measuring profit opportunities usually

mentioned in the theory is either omitted in empirical studies, because of limited data availability, or

found to be non-significant.

In addition, the validity of the foreign bank motivation and entry modes has not been yet

established for the transition countries due to the modest attention given to their empirical

verification. Our study tries to fill the existing gap in the multinational banking literature building

our study upon previous empirical work. We focus on this aspect arguing that transition countries are

an interesting testing ground for theories on multinational banking. In 1990s, the economy and

financial market were characterized by lack of competition and close regulation. The situation

changed in the 1990s due to political transformation, when the financial markets were liberalized

and competition in the market increased. As a consequence, the transition economy and thus the

banking sector offered several profit opportunities to be exploited by foreign banks. Yet, it is still

unclear which motives for foreign banks had been the leading in the decision to go into one of the

transition countries.

4. Economic determinants contributing to FDI in CE banking sectors

As have been shown in the previous section, there are various theories explaining the motives

for banks to go abroad. In this section, we review the determinants that have been provided by the

literature as the motivation of foreign banking and present the proxies we have included in our

regressions. Our main goal of this paper is to provide an answer, which determinants have been the

leading ones for foreign banks, in their decisions to open a subsidiary in one of the CE countries.

However, we have decided to organize those determinants into four major groups. Each of the group

represents a different hypothesis providing an explanation on the motives behind foreign bank

expansion into one of the CE country. In addition, we hope this way to be able to establish the

relationship between the motivation and the model of entry chosen by the foreign banks. We review

the determinants of entry modes of foreign banks in more detail in the sub-section below. Given the

above considerations, we present the following four hypotheses to be tested.

Hypothesis 1: The foreign bank involvement is positively related to client’s presence in

the CE country

Hypothesis 2: The foreign bank involvement is positively related to market opportunities

in the CE country

Hypothesis 3: The foreign bank involvement is positively related to low efficiency of

domestic banks in the CE country.

Hypothesis 4: The foreign bank involvement is positively related to favourable

regulations in the CE country.

As have been already mentioned in the past the pattern of foreign bank expansion has been

dominated by the follower relationship. Under this hypothesis banks decided to expand in order to

provide services to their home country clients in countries abroad. At the same time those banks

operating abroad have gained a growing understanding of foreign markets and have increased the

range of their operation and services. Thus, we believe that the pattern of foreign bank has some

characteristic that are peculiar to the banking industry, yet the choice of expanding abroad depends

on a wider range than just one single factor. Therefore our hypotheses should be seen with great

caution as the variables presenting them may be significant simultaneous and it is difficult to asses,

which of them may be more important on a stand alone basis.

Our first measure controls for the first hypothesis to be tested, which have been shown in

many previous studies as an important motivation for foreign bank expansion. As a proxy for the

follower hypothesis we use as proxy the stock of direct investments excluding financial industry into

one of the countries in the CE from the country of origin of the foreign bank. The variable non-

financial FDI was expressed as ratio to the domestic country GDP. We employ it as a lagged one

measure as the rationale is that home banks will follow their customers abroad so that they can

provide services for them in the foreign operations. Thus, we expected that there is a positive

relationship between foreign direct investments and the expansion of banks abroad. A strong positive

relationship has been reported in the studies of Nigh et al. (1986) and Goldberg and Johnson (1990).

They have found a positive relationship between the US banks foreign activities and the size of US

foreign direct investments abroad.

Liquid liabilities

Another common assumption in the empirical literature is that a well developed financial

market may attract foreign banks due to external agglomeration economies (Davis 1992,

Kindleberger 1974). The rationale behind is that investors consider whether to invest in foreign

banking, the size and structure of the particular financial system is likely to be one of the factors they

take into account. Thus, Konopielko (1997) formulated a hypothesis that with the economic

development of other countries the significance of the follow the client rationale for foreign entry in

banking will diminish and subsequently be replaced by search for client’s behaviour, which presents

our second hypothesis in our paper.

This claim was supported by Dopico and Wilcox (2002) who argued that the size of the host

country’s banking market is one of the significant determinants of foreign expansion. They found

that foreign banks are more pervasive in countries where banking is more profitable and where the

banking sector is smaller relative to GDP. In order to control for these characteristics, we considered

size of the financial sector and the banking sector, whereas the profit opportunities present our next

hypothesis and the proxies will be described later. In our study the size of the domestic banking

market of one of the CE countries is a location-specific determinant of foreign bank expansion.

We employ liquid liabilities, which are defined as the ratio of liquid liabilities of the financial system

to GDP. We consider this variable, as it is usual in the finance literature, as a proxy of financial

depth since it represents the size of the formal financial intermediary sector. The implicit assumption

is that the size of the financial system is positively related to the foreign bank entry. Including liquid

liabilities to GDP might also control for the effects of financial system underdevelopment that differ

systematically by income levels across countries.

In this study, similar to the study of Grosse and Goldberg (1991), the size of the banking

market is proxied by the deposits held by the domestic banks to GDP. This variable allows us to see

whether smaller and less developed domestic banking sectors attract more foreign banking. In theory

the larger the domestic banking market, the greater the number of potential customers. This would

suggest that there should be a large number of foreign banks willing to invest in large markets in

order to take advantage of the market’s potential. In our study we expect a positive relation between

the size of the banking market and the number of foreign banks. Especially in case of Poland, which

is the biggest country in the region, we anticipate to report a positive relation of foreign presense and

the size of the banking market.

Concentration

Steinherr and Huveneers (1994) provided evidence that foreign banking was less common in

countries where a smaller number of domestic banks dominated banking. They argued that greater

concentration limited the choices available to borrowers, forced domestic firms into relationships

with the dominant banks and stunted the development of an arms-length lending market. In such a

market, even though banking might be profitable, foreign banks might be unable to enter. We test for

this by including a five-bank concentration ratio in our model specifications and expect a negative

relationship with foreign banking entry.

Market capitalization and turnover ratio

Demirgüç–Kunt and Levine (1996) documented that in different countries the extent of stock

market development highly correlates with the development of banks and other financial institutions.

We use the value of domestic equities on domestic exchanges divided by GDP to measure the

development of the stock market. In addition, we use the values of equities traded to GDP, which

reflect the activity of stock markets in transition countries. The total value traded ratio is frequently

used to gauge market liquidity because it measures market trading relative to economic activity. On

one side, we would expect significant positive relationship between the development of banking

sector and capital markets in transition countries. On the other side, the more active and developed

the capital market, the greater the competition with the banking industry. Thus, we may also assume

a negative relation between stock market development and activity and foreign bank entry.

Net interest margin and overhead costs

In order to test the importance of market opportunities in the transition countries we employ

two different variables. To test whether the overall profitability of banking in the host country

influenced foreign banking, we include a profitability measure – a net interest margin (Claessens et

al. 2001, Dopico and Wilcox 2002). High net interest margins in the CEE countries in comparison to

other developed countries have been observed in the past (Allen et al., 2006). However, Lensink and

Hermes (2004) find that in developing countries, foreign entry is associated with shrinking margins.

Similar results were previously reported by Claessens et al. (2001), who demonstrated that for most

countries higher foreign ownership is associated with a reduction of costs and net interest margins

for domestically owned banks. Those results were confirmed recently by Allen et al. (2006) in a

study on the EU-25 financial system. The authors have shown a gradually decline of the interest

margins in the CEE region over the last decade and the convergence towards the levels reported in

the developed countries.

Another source of motivation to expand abroad can be the foreign banks’ efficiency relative

to that of the domestic banks. According to Tschoegl (1987), high overhead costs, low efficiency of

management and the cost of capital can increase the likelihood of foreign bank expansion into the

market. In the Czech Republic and Poland foreign owned banks were more efficient than domestic

owned banks and this was not due to scale differences or the structure of activities (Weill 2003),

which would confirm our hypothesis. Therefore, to estimate and control for inefficient domestic

banks, we include the measures of overhead costs.

We will use this two variables in order to test our third hypothesis that foreign banks expand

into those markets, where are the highest profit opportunities and the lowest efficiency of banks. We

expect that foreign banks entering the market will see an opportunity to export their knowledge,

which will give them a competitive advantage in the domestic banking markets. Thus, we assume

that the foreign banks are probably the most efficient in their home market. The combination of high

profit opportunities and the inefficiency of the domestic banks provide the motivation for the third

hypothesis on foreign bank expansion into the CE countries. Therefore we expected that those two

variables will have a positive effect on the foreign entry into the region.

Legal origin, creditor rights and banking regulations

According to Goldberg and Saunders (1980) international expansion may be affected by both

economic and regulatory factors. In a series of influential papers La Porta et al. (1997, 1998) stress

that the cross-country differences in the legal environment and their enforcement may influence the

financial structure. Rajan and Zingales (1998) argue that bank-based financial structure prevails and

is more effective in countries with weak legal systems and poor infrastructures. While, Darby (1986)

presents that the rate of growth by particular parent countries may be stimulated by home country

regulation that reduces domestic profitability. To examine this issue, we follow La Porta et al.

(1997) and consider institutional factors that measure the quality of the legal environment both

overall and specifically for creditors.

We used the data on the legal origin from the La Porta et al. (1997, 1998) studies, the countries were

classified into five legal origin groups. With respect to legal origin, La Porta et al. (1997) distinguish

first between common law and civil law countries. The civil law comes from Roman law and relies

heavily on legal scholars to formulate its rules, whereas the common law originates from English

law and relies on judges to resolve disputes. It is common to further distinguish between French,

German and Scandinavian civil law countries. In addition, we separately control for the legal origin

of the transition economies were the legal system represents currently a combination between the

French and German civil law.

La Porta et al. (1997, 1998, 2000) argue that common law countries protect both shareholders and

creditors the most. More specifically, La Porta et al. (1998) show that countries based on the English

tradition have laws that emphasize the rights of creditors to a greater degree than the French,

German, and Scandinavian countries. French civil law countries give the weakest protection to

creditors, whereas German and Scandinavian civil law countries are somewhere in between. La Porta

et al. (1998) also examine enforcement quality. Countries with a French legal heritage have the

lowest quality of law enforcement, while countries with German and Scandinavian legal traditions

tend to be the best at enforcing contracts. In our study the variable English Legal Origin equals one

if the country has an English legal tradition and zero otherwise. Similarly, French Legal Origin,

German Legal Origin, Scandinavian Legal Origin and Socialist Legal Origin take on appropriate

values of one and zero for each country.

Legal and regulatory systems that facilitate the repossession of collateral and that grant

creditors a clear say in reorganization decisions are likely to encourage the development of banks.

As shown by La Porta et al. (1997) greater creditor right is positively associated with financial

institutions development. Thus, reforms improving creditor protection may attract foreign bank entry

into the transition countries. In terms of the specific indicators, we follow Pistor et al. (1999, 2000)

who modify the index of La Porta et al. (1997) by excluding one and including two additional

variables, referring the index to the problems of transition countries. In our analysis, the index ranges

from zero to five and aggregates creditor rights.

The creditor rights variable is described in La Porta et al. (1998) and Pistor (1999). We expect that

those countries with the legal systems that assign strong rights to creditor are more likely to support

the growth of banks including those of foreign origin.

Aliber (1984) and Hultman and McGee (1989) noted that a host country’s regulatory

environment affect foreign banking. Using the Barth et al. (2001) analysis of commercial bank

regulations, we construct an aggregate index of regulatory restrictions on bank activities in

securities, insurance, and real estate markets and restrictions on bank ownership of non-financial

firms. This measure of regulatory restrictions on bank activities gauges bank power and therefore

allow us to test whether restrictions on the range of permissible banking activities affected foreign

banking. Therefore, we anticipated a negative relation between foreign bank entry and regulatory

restriction on bank activities.

Economic growth and inflation

Weller and Scher (2001) claimed that the real economic growth and the level of development

of domestic banking determine foreign banks’ presence in the host countries. In order to control for

economic growth we include a variable representing difference in economic growth between host

and home country of the foreign bank. We expect to find a positive correlation between the

difference in economic growth rate and the presence of foreign banks.

A series of recent papers have addressed the study of the long-run influence of inflation on

growth and financial system development (Barro 1995). The main findings of this body of empirical

literature may be summarized as follows. First, inflation has a negative temporary impact upon long-

term growth rates. This effect is significant and generates a permanent reduction in the level of per

capita income. Second, inflation not only reduces the level of investment but also the efficiency with

which productive factors are used.

Exchange rate and corporate tax rate

To consider long-term economic conditions of the countries in our study, we include two

additional variables. The first is the change in foreign exchange rates of the currency of the domestic

country against the Euro currency. We use the exchange rate towards Euro as most of the foreign

banks stem from the Euro area. We will test whether fluctuations in the value of the host countries’

currencies affect the level of foreign investment in banking in CE countries.

Operating a banks subsidiary abroad will involve substantial flow of foreign currencies. A

depreciation of domestic currency may motivate foreigners to acquire the control of domestic bank.

In addition, when the host countries’ currencies depreciate, foreign banks may reduce their

repatriated income and increase their reinvestment in the host countries, as they may want to avoid

exchange rate losses. On the other hand, when the host countries’ currencies appreciate with respect

to foreign banks currencies, capital flows is expected to decrease as it becomes more expensive for

foreign investors to invest in one of the CE countries. Such a negative relation has been reported by

Goldberg and Saunders (1981) and Froot and Stein (1991).

Our second variable is the level of corporate tax in the CE countries. In the literature overseas

bank expansion is also frequently attributed to the variations in tax treatment of banks in different

countries. Thus, taxes may influence the level of foreign direct investment in banking in the region.

The corporate tax regime in use may therefore determine whether or not a country is an attractive

location for a foreign bank to establish a subsidiary. At the same time the foreign entry can be a

response to moves by the host country to attract foreign banks by offering more favourable tax

treatment than the bank’s home country or in order to increase competition in the financial services

sector.

Geographic location

The geographic differences between the home and host nations may proxy not only the

geographical, but also the cultural distance between countries. Given the importance of information

about customers as well as of knowledge of outlet markets in banking, we expected a negative

relationship between distance and foreign entry. In addition, in several studies the geographical

distance has been applied in the literature as a proxy for the degree of economic integration (Ball and

Tschoegl 1982, Grosse and Goldberg 1991).

We measure the geographic difference using the distance between banks host and home country. A

negative relationship may indicate that the difficulty of operating a subsidiary in a foreign country

grows as geographical and cultural differences increase. Focarelli and Pozzolo (2001) have reported

that the distance increases the probability of market entry by acquiring shares in a foreign bank.

While, Magri et al. (2005) presented that the likelihood of operating a foreign bank in Italy diminish

as geographical and cultural differences increased.

EU membership

Finally, following Magri et al. (2005) we introduced also a dummy in the estimates to

identify countries belonging to the EU. We assume that EU banks should have an advantage to other

foreign banks due to lower entry barriers and extended the activities that are permitted to undertake

under the EU Directive. Therefore we expected the variable to exert a positive effect, which has been

reported in Italy by Magri et al. (2005).

4.1 Economic determinants and the entry modes of foreign banks

In principle, the factors affecting the decision about entry into the CE countries may vary with

the mode of entry chosen by a bank. Since such determinants as high net interest margin or great

economic development may promote one form of entry, the others as tax relieves or high

concentration of the banking sector may influence positively the other formal structures. Hence, an

organizational form is not an arbitrary formality but rather a function of foreign bank’s strategy and

scope of its activities willing to provide in the host country. In addition, foreign bank must take into

constitute an economic environment existing both in home and host countries. The legal form chosen

by a foreign bank is also of great substantive importance from another reason. It may under certain

circumstances have effect on the stability of both home and host banking sectors. The first one may

be affected by a failure or great losses of a parent’s bank institution in a host country. From the point

of view of a host country, the regulations promoting particular modes of entry may prevent country

from a crisis or at least attenuate their effects (Tschoegl 2003).

The regulatory environment of the CE countries has changed over time. Furthermore, it was also

different among the countries themselves. In principle, the foreign banks could enter the CE

countries either by acquiring or merging with a domestic bank or through de novo operation. We

distinguish among the operational forms a subsidiary or branch of a parent company, as well as a

representative office of a bank. Since bank’s representative office can not provide any financial

services in a host country, we do not consider them in our analysis.

A branch is defined as an integral part of the parent organization and in our opinion it constitutes

the highest level of foreign banking penetration in a host country. The branch shares a parent’s credit

rating, lends and trades on the parent’s full capital base. Thus, it may have substantial advantage in a

host country banking market. However, a branch may go insolvent if its parent goes bankrupt or

other way around. Thus, this mode of entry requires a careful supervision of both home and host

country’s authorities. The Polish banking law allowed the foreign banks to enter via branches since

1989. The licensing policy was also very liberal at that time. The only requirement to be fulfilled by

a foreign bank to set up a branch was an agreement with the National Bank of Poland. However,

despite that, Poland did not experience in wave of branches. The situation has not changed

significantly until now. One of the reasons was that the Polish National Bank was not willing to

allow foreign banks to operate as branches easily.

The situation looked differently in Hungary. The Hungarian regulatory authorities abolished the

entry via branch until the 1997 and even after the implementation of the Second Banking Act

Amendment in 1997, which provided a possibility to establish a branch by a foreign institution, this

form effectively qualified as subsidiaries in terms of capital requirements and operations (Kiraly et

al. 1999). Although, the operation activities via branches are allowed, the country has not

experienced any opening of branches till 2004.

In the Czech and Slovak Republics the situation looked very similar to Poland. The banking laws

from their beginning allowed foreign banks to set up branches assumed they received a formal

approval from the host national central bank.

Since the accession into the EU, the member states has been granted a “single passport”, which

assumes that all credit institutions authorized in an EU country would be able to establish branches

or supply cross-border financial services in the other countries of the EU without further

authorization, provided that a bank was authorized to provide such services in the home state

(Dermine, 2005).

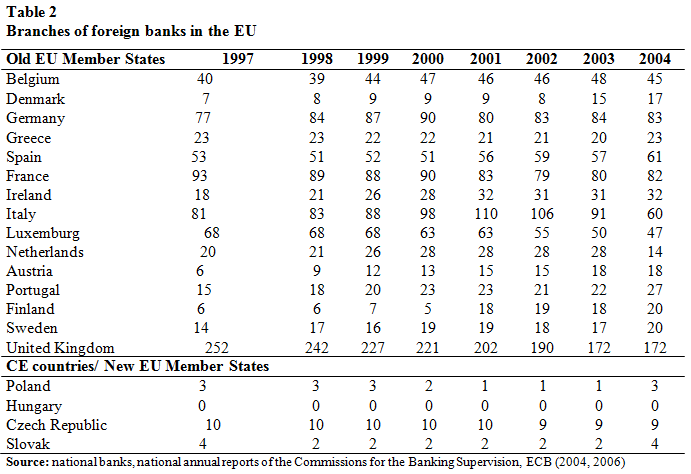

Table 2 shows that branch has been very rare mode of penetrating CE banking markets

comparing with other European countries despite any specific restrictions (excluding Hungary) per

se imposed by the regulatory authorities on this organizational form. One reason for that could be

that branches are very sensitive to the location-specific risk (Tschoegl 2003). Hence, in the course of

instable political and economic situation, the parent banks preferred to choose other organizational

forms, which could put them in the more secured position and did not require risking their

reputations once the expectations of great economic development would not have been met. Wengel

(1995) has proved it empirically concluding that the parent tends to send branches to wealthier

countries, while the less sophisticated forms to the developing ones. On the other hand, setting up a

branch of foreign bank should be justified by sufficient activities in the area for which a branch

offers an advantage (Heinkel and Levi 1992). Therefore, many studies on international banking

argue that branches are not attracted by great profit opportunities and hence they do not state in the

direct competition with other legal forms (Miller and Parkhe 1998). In the US, Heinkel and Levi

(1992) found that setting up a branch was positively correlated with the development of the domestic

money and capital markets, in which the foreign branches participate allocating the deposits of their

customers collected in the home market. Hence, we may assume that the development of the capital

markets in the CE countries as well as better creditor rights may positively affect the inflow of

branches into this region.

A subsidiary is a separate legal entity incorporated in the host country, mostly acted as wholly-

owned subsidiary company of a parent bank and often it is engaged in a broader range of financial

services than branches. Since the beginning of transformation the subsidiaries were the most

frequent forms of entering the CE banking markets. Heinkel and Levi (1992) point out that

subsidiaries differ from other forms of banking operations and thus respond differently to various

factors. First, they operate in the different area of competition than other legal forms. Second, the

parent bank has different motivations on establishing it. In the CE the history of subsidiaries can be

divided into two periods. The first, early 1990s when the subsidiaries were set up and second, the

middle of 90s when the privatization process began. The motivations of entry through this type of

organizational form have also changed across time. In the early of 1990s, the major motive driving

an establishment of a subsidiary was to provide high-quality services to these companies which had

invested in or traded with the CE countries as well as their foreign employees on the spot (Majnoni

et al. 2003). Thus, these subsidiaries were mostly engaged in the wholesale and corporate banking,

especially depositing, trade and exchange foreign operations. The best examples are Commerzbank

in Hungary (1993) and Czech Republic (1991), Bank of America (1990) and Citibank (1991) in

Poland. It should be also mentioned that many of these banks were motivated to enter by the tax

relieves which were very common practice at that time in CE countries. Unlike branches which are

subject to the home country’s regulations and tax and accounting standards, this could be an

additional motivation for setting up a subsidiary.

In the middle of 1990s, during the time of the major bank privatisations, the motivations behind

setting up a subsidiary changed. In this period foreign banks noticed an opportunity of acquiring

large domestic universal banks. Some of them acquired subsidiaries and even merged them with

already existing operation or branches. Apart from it in this period many subsidiaries of the foreign

banking institutions began to operate, especially in consumer finance sector as Porsche Bank, Opel

Bank, Fiat Bank or Sygma Bank.

Following the above argumentation, we would argue that the establishment of branches and

subsidiaries would be motivated by different factors and that they do not stay in direct competition to

each other.

As mentioned already, the most common mode of penetrating the CE banking markets which

became in the middle of 1990s was an acquisition of the existing banks. The entry through M&As

was the quickest and the simplest mode of establishing presence in the CE countries. Mostly, it took

place during the privatization process when the governments offered share in the domestic banks in

order to save them or in exchange for the takeover of bad portfolios. This process lasted till the

entrance of the CE countries into the EU. One reason for that were the administration restrictions

imposed by the governments on the acquisition of majority stakes by foreign institutions. In the

Czech Republic, for example, the acquisition of majority stakes to the strategic investors was

abolished. Thus, foreign investors were able to buy only minority interests in the domestic banks in

the first years (Bonin and Wachtel 1999). The Hungarian banking law, on the other hand, required

an agreement of President of the National Bank on acquisition of stakes in a domestic bank above 10

per cent. However, it represented the most liberal licensing policy and the privatization process with

the possibility of acquisition of majority later on. In Poland, the government started to sell majority

shares of the state-owned banks to foreign investors at the end of the 1990s (NBP 2001).

Tschoegl (2003) point out that the type of an organizational form chosen by foreign banks to

expand, is often closely connected with its strategy. He argues that the conditions which drew

foreign banks to enter developing countries erode over time and then some will have to withdraw

their local operations. Therefore, he distinguishes among others two types of banks’ strategies. First,

prospectors who enter via wholly-owned subsidiaries or joint-ventures in order to engage in

exploratory foray. Second, restructures who acquired large domestic banks in privatization process

and treat their investments rather as long-term commitment. Tschoegl (2003) also argues that as

foreign banks have no comparative advantage in retail banking vis-à-vis host country banks in the

long-run perspective, the acquisition of the domestic banks can be the only possible method to get in

this business and remain in it for certain, at least, medium term. In this sense, this mode of entry

gave the entering foreign banks much greater comparative advantage as setting up a branch or

subsidiary.

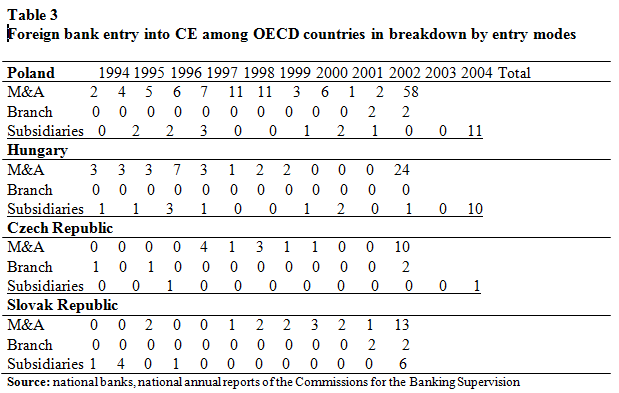

Tables 3 and 4 show the number of foreign bank entries into the CE countries in breakdown by

entry modes and entering countries during the period 1994-2004. As it can be seen, the M&As have

been the most favourite entry mode of the foreign banks into CE markets during the last years.

[Table 3] and [Table 4]

The high number of the yearly entries by M&As can be a result of the banking regulations and

restrictions imposed by the governments in the CE countries on acquisition of majority stakes in the

domestic banks and as well as other forms of entry. In the course of relaxing the restrictions, the

same foreign banks could further increase their stakes in the domestic banks. An entry via subsidiary

was the second most common mode of internationalization into the CE banking markets and

dominated over the other methods mostly at the beginning and middle 1990s.

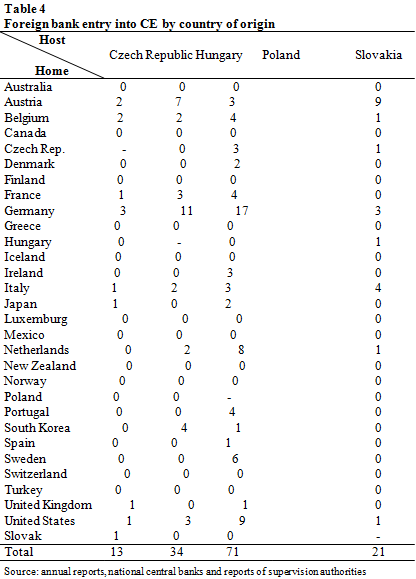

Table 3 shows also that Poland had the highest number of foreign bank entries. However, as we

compare the assets of the foreign banks between individual banking sectors presented in the table 4,

we can observe that the Czech Republic and Slovakia are among the CE countries with the highest

share of the banking assets in the hands of the foreign banks. Furthermore, Table 5 shows that

foreign bank entries came mainly from the neighbours countries of the CE countries.

[Table 5]

5. Data and Methodology

This section describes our data set and the two econometric methods that we use to assess the

economic determinants of foreign bank expansion into the four CE countries. First, we employ

Poisson regression with our sample for the four CE countries and the OECD countries over the

1994–2004 period. Second, in order to evaluate the economic determinants and the entry mode of a

foreign bank into the CE market we use a bivariate probit model using our sample over the 1994–

2004 period. In our study we concentrate only on the OECD countries as almost all foreign banks

operating in the CE region were from the OECD member countries. All variables employed in our

analysis are presented in the Appendix.

5.1 Data

In our paper we evaluate the economic determinants of foreign bank entries and its entry

modes into the four local banking markets in CE. In order to analyze those markets we use yearly

data on countries and banks in the four CE countries, namely the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland,

Slovakia for the period 1994-2004. These countries have shown widely different policies towards the

mode of foreign bank entry as we have presented above.

Our final sample contains 110 cross-border entries either by M&A or through setting up a

branch or subsidiary by a OECD foreign bank in one of the host countries. We established those

transactions using public information as national and international press coverage and compared it

with the list of foreign banks compiled by national bank supervisors.

In our study we define a foreign bank entry as to be followed by three forms: entry by setting up

a branch, subsidiary or/and via M&A.

We define a subsidiary or branch as a organisational form that received a domestic license or

approval by domestic bank supervisory institution. The transformations of the already existing

foreign banks, i.e. the transformations of branches into subsidiaries or vice versa are not considered

as entry and therefore are not included in our analysis. We argue that they can be driven by other

market determinants, which might not be observable for the non-existing foreign banks.

We define the entry through M&A as an acquisition of minimum of 5 per cent shares in a

domestic bank by a foreign banking institution as well as merger of domestic and foreign operation

in a host country. In our paper we are interested only in the horizontal foreign entry, which are

assumed to offer a broad potential for cost and profit efficiency improvements. Other types of

transactions, such as government owned banks or other financial institutions acquiring an bank are

excluded because they may be motivated by a different set of considerations. Moreover, our analysis

does not include mergers or acquisitions of the domestic banks with other domestic banks.

5.2 Poisson regression

In order to analyze entry decisions into the CE countries, we consider the number of entries

of foreign banks at time t into Poland, Hungary, Czech Republic and Slovak in breakdown by a

country of origin, conditioning on the specific groups of the regressors such as host-country

characteristics, physic relationship between host and home country and potential determinants of

entering. In contrast to other analysis, we are not strongly interested in the characteristics of banks

entering the CE countries as this area has been covered by many researchers whose work can also be

applicable to the four countries in our study.5 Hence, we are mainly interested in answering the

following questions:

a) How much did the host-country characteristics and in particularly macroeconomic conditions

matter in the entrance process of foreign banks into CE? Which of them did the foreign banks

consider to be the most important?

b) How much did the host-country banking regulations influence the number of foreign entries?

c) Which of the suggested in the section 2 determinants of banking internationalization did the

foreign banks mostly follow deciding on entry the CE countries?

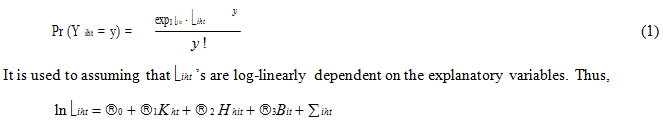

Accordingly, we estimate the following choice model:

where y = number of entering banks from country i into country h at time t and Y1ht, Y2ht, Y3ht,… Y29ht

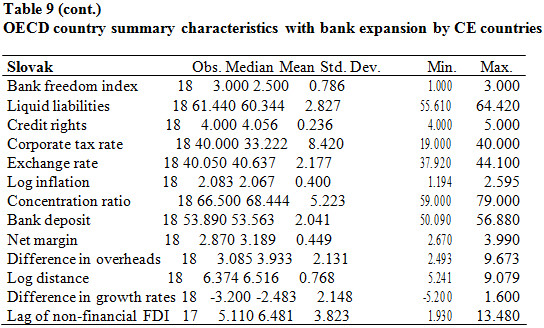

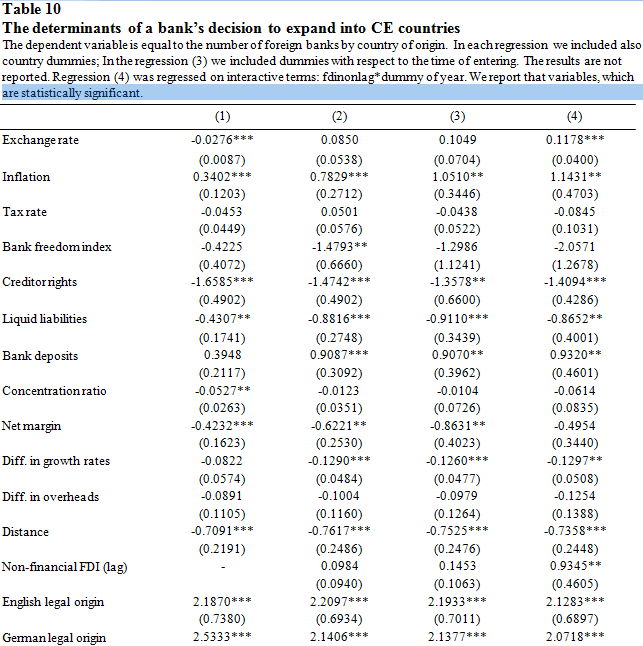

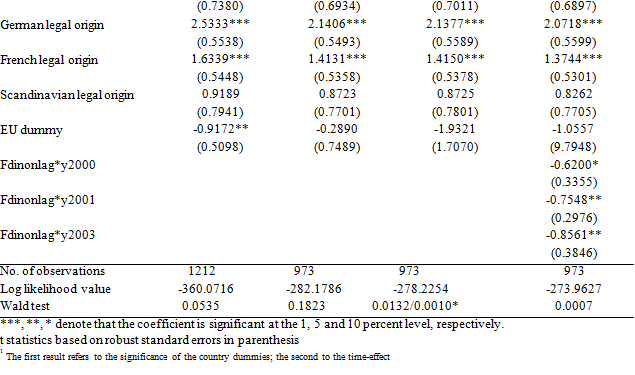

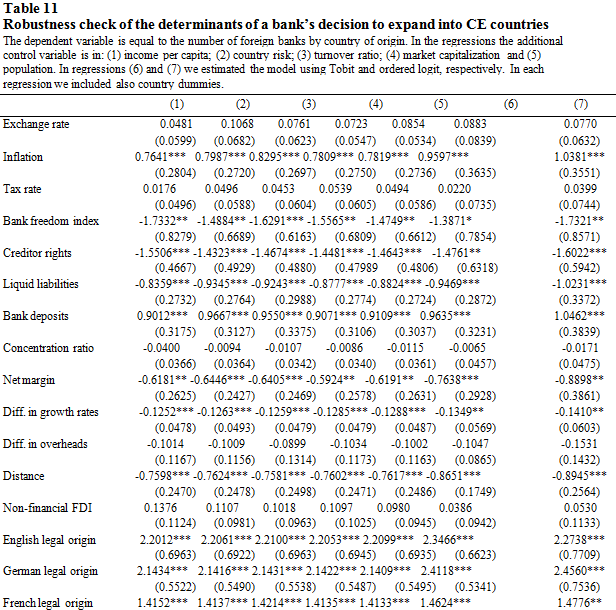

have independent Poisson distribution with parameters ![]()