A new study offers proof that prompt treatment of depression may reduce the risk of dementia in particular patient groups. Depression has long been linked to an elevated risk of dementia.

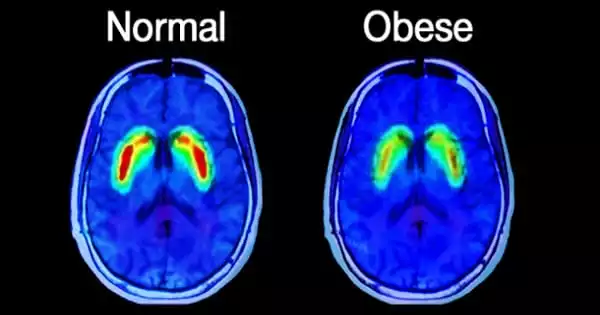

Dementia is a disabling neurocognitive illness that primarily affects older persons and affects about 55 million people globally. Determining strategies to diminish or prevent dementia would assist to lessen the burden of the disease even though there is no effective cure for it.

The study, led by Jin-Tai Yu, MD, PhD, Huashan Hospital, Shanghai Medical College, Fudan University, and Wei Cheng, PhD, Institute of Science and Technology for Brain-Inspired Intelligence, Fudan University, Shanghai, China, appears in Biological Psychiatry, published by Elsevier.

Data gathered by the UK Biobank, a population-based cohort with more than 500,000 people, was utilized by Professors Yu and Cheng. More than 350,000 people participated in the current study, including 46,280 people who had depression. 725 of the study’s depressed participants experienced dementia over the course of the investigation.

Previous research evaluating whether depression treatments, such as medication and psychotherapy, could reduce the risk for dementia generated contradictory findings, leaving the issue open.

The new findings shed some light on previous work as well. The differences of effectiveness across depression courses might explain the discrepancy between previous studies.

Professor Wei Cheng

“Older individuals appear to experience different depression patterns over time,” said Professor Yu. “Therefore, intra-individual variability in symptoms might confer different risk of dementia as well as heterogeneity in effectiveness of depression treatment in relation to dementia prevention.”

The participants were then divided into one of four courses of depression to address this heterogeneity: increasing course, where mild initial symptoms gradually worsen; decreasing course, where moderate or severe symptoms initially appear but then subside; chronically high course, where severe depressive symptoms persist; and chronically low course, where mild or moderate depressive symptoms persistently persist.

As predicted, the study discovered that compared to non-depressed subjects, depression significantly increased the incidence of dementia by 51%. The severity of the risk, however, depended on the course of the depression; those with growing, chronically high, or chronically low course depression were more susceptible to dementia, whereas those with decreasing course depression were at no higher risk than participants without depression.

Most importantly, the researchers sought to determine if receiving depression treatment could reduce the elevated risk for dementia. Overall, persons with depression who received treatment had a 30% lower risk of dementia than participants who did not.

When the participants were broken down by depression course, the researchers discovered that those with chronically low and increasing depression courses experienced a reduction in dementia risk with treatment, whereas those with a chronically high course did not experience any reduction in dementia risk.

“Once again, the course of ineffectively treated depression carries significant medical risk,” said Biological Psychiatry editor John Krystal, MD. He notes that, “in this case, symptomatic depression increases dementia risk by 51%, whereas treatment was associated with a significant reduction in this risk.”

“This indicates that timely treatment of depression is needed among those with late-life depression,” added Professor Cheng. “Providing depression treatment for those with late-life depression might not only remit affective symptoms but also postpone the onset of dementia.”

“The new findings shed some light on previous work as well,” said Professor Cheng. “The differences of effectiveness across depression courses might explain the discrepancy between previous studies.”