Scientists from the Medical College of Wisconsin Cancer Center and an international team of partners have developed mice with a better hormone profile that favors the growth and spread of human breast cancers implanted in them.

Breast cancer is cancer that develops in the breast and spreads to other parts of the body. It can begin in either one or both of the breasts. When cells proliferate out of control, cancer develops. Breast cancer affects almost exclusively women, although it can also affect men.

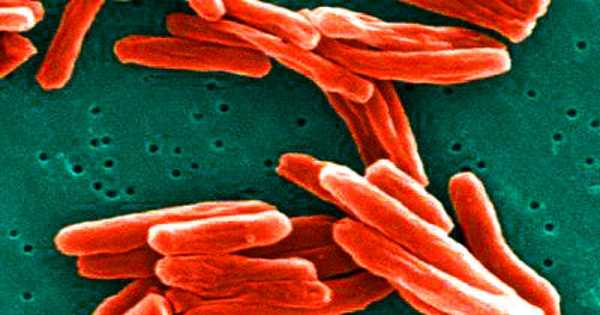

Estrogen receptor(ER)-positive tumors are responsible for the majority of breast cancer mortality. Growing untreated ER-positive breast cancers from patients in mice has been a long-standing difficulty.

Efforts to find better medications or therapeutic combinations have been impeded by a lack of such human breast tumor models. More effective treatments are required to prevent the development of resistance to present medicines and, as a result, to minimize breast cancer mortality.

It’s critical to remember that the majority of breast lumps are benign and not cancerous (malignant). Breast tumors that aren’t cancerous are abnormal growths that don’t spread outside of the breast. Although benign breast lumps are not life-threatening, they can raise a woman’s risk of developing breast cancer.

The hormone prolactin, which is well recognized for stimulating milk production in mothers, is susceptible to ER-positive breast cancers. The researchers had previously shown that mouse prolactin does not activate human prolactin receptors, and they hypothesized that this hormonal flaw was responsible for the poor growth of human ER-positive breast cancer in mice.

This new study claims that by manipulating the mouse prolactin gene, the researchers were able to create a mouse breed with blood levels of human prolactin that are identical to those found in patients.

The NSG-Pro mouse model promotes significantly increased growth of implanted ER-positive human breast tumors. Prolactin collaborates with estrogen and Her2, two well-known breast cancer growth factors, according to tumor molecular pathway analysis.

We are particularly excited about the opportunity to study distant metastases and test the effectiveness of drugs on advanced stage ER-positive breast cancer because until now such experimental models have not been available. This is particularly important because breast cancer patients die from distant metastases.

Hallgeir Rui

In NSG-Pro mice, the team has created a panel of transplantable estrogen-dependent patient-derived breast tumor models. When injected into the mammary glands of NSG-Pro mice, several of the novel tumor lines mimic disease course in patients by migrating to distant organs. The study was published in the journal Science Advances on September 15th.

“We are particularly excited about the opportunity to study distant metastases and test the effectiveness of drugs on advanced stage ER-positive breast cancer because until now such experimental models have not been available,” says Hallgeir Rui, WBCS Endowed Professor of Breast Cancer Research; director of the MCW Tissue Bank; and professor and vice-chair of Research, Pathology at MCW. “This is particularly important because breast cancer patients die from distant metastases.”

Surprisingly, the team discovered that two separate prolactin-blocking medications reduced the growth of cancer cells that had migrated to the lungs after surgically removing the primary tumors from the mice mammary glands.

Although more research is needed, the findings suggest that prolactin-targeted medicines could help certain patients with metastatic ER-positive breast cancer.

“The NSG-Pro mouse model provides previously inaccessible precision medicine approaches for ER-positive human breast cancers,” said Yunguang Sun, MD, Ph.D., joint lead author of the study and assistant professor in Pathology & Laboratory Medicine at MCW.