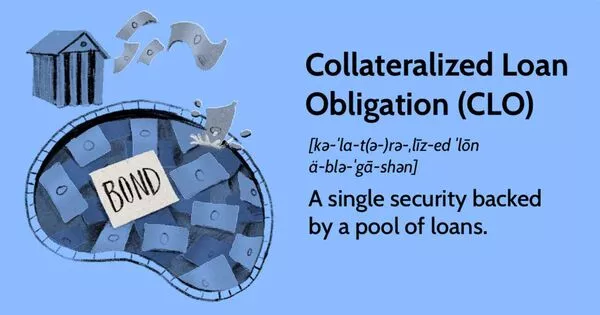

Collateralized loan obligations (CLOs) are a type of structured asset-backed security (ABS) that are backed by a pool of loans, typically corporate loans or other types of debt. The loans are often pooled together and then divided into different tranches, with each tranche having a different level of risk and return. CLOs are a type of securitization in which payments from multiple small and large business loans are pooled and distributed to different classes of owners in different tranches. A collateralized debt obligation (CLO) is a type of debt obligation.

CLOs are typically structured as follows: the loans in the pool are used as collateral for the CLO, which is then divided into different tranches. The most senior tranche (also known as the “AAA” tranche) is typically the most highly rated and has the lowest risk of default, while the more junior tranches have higher levels of risk but also offer higher potential returns.

Investors in CLOs can be hedge funds, pension funds, insurance companies, or other institutional investors seeking exposure to the corporate loan market. The CLO manager is responsible for managing the pool of loans and ensuring that the payments are made to the different tranches of the CLO.

CLOs became popular in the early 2000s, and they have since become a significant source of funding for corporate borrowers. However, CLOs are also subject to risks, including credit risk (the risk that the loans in the pool will default), interest rate risk (the risk that changes in interest rates will affect the value of the CLO), and liquidity risk (the risk that investors will be unable to sell their CLO holdings).

Leveraging

Each class of owner may receive higher yields in exchange for being the first to lose money if the businesses fail to repay the loans purchased by a CLO. The actual loans are multimillion-dollar loans to privately or publicly owned businesses. Known as syndicated loans, they are originated by a lead bank with the intention of immediately “syndicating,” or selling, the majority of the loans to the collateralized loan obligation owners.

The lead bank retains a minority stake in the highest-quality tranche of the loan while typically acting as a “agent” for the syndicate of CLOs and servicing loan payments to the syndicate (though the lead bank can designate another bank to assume the agent bank role upon syndication closing).

Loans to companies that owe an above-average amount of money for their size and type of business, usually because a new business owner borrowed funds against the business to purchase it (known as “leveraged-buyout”), the business borrowed funds to buy another business, or the enterprise borrowed funds to pay dividends to equity owners, are usually referred to as “high risk,” “high yield,” or “leveraged.”

It’s no surprise that CLOs have grown in popularity in markets in recent years. They have historically provided an enticing mix of above-average yield and potential appreciation. However, for many investors, the basics of how they work, the benefits they can provide, and the risks they pose are wrapped in complication, which is why the financial media and some market participants frequently misinterpret them.