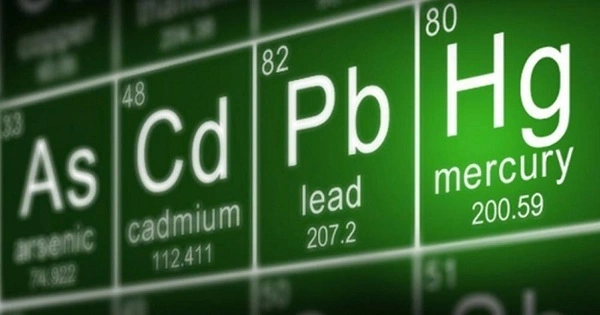

Chronic lead, cadmium, and arsenic exposure has been linked to an increased risk of cardiovascular disease. These heavy metals are toxic to the human body and can harm many organ systems, including the cardiovascular system.

According to a new statement, most people around the world are regularly exposed to low or moderate levels of lead, cadmium, and arsenic in the environment, increasing their risk of coronary artery disease, stroke, and peripheral artery disease.

According to a new American Heart Association scientific statement published today in the Journal of the American Heart Association, an open-access, peer-reviewed journal of the American Heart Association, chronic exposure to low levels of lead, cadmium, and arsenic through commonly used household items, air, water, soil, and food is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease.

The evidence linking chronic exposure to low or moderate levels of three contaminant metals – lead, cadmium, and arsenic – to cardiovascular diseases such as coronary artery disease, stroke, and peripheral artery disease is reviewed in this scientific statement. It focuses on the clinical and public health implications. Environmental toxins are not currently considered traditional risk factors for cardiovascular disease. The field of environmental cardiology identifies exposure to pollutants including contaminant metals as modifiable risks for cardiovascular disease.

Cardiovascular health may be improved with a multi-pronged approach that recognizes environmental cardiology and includes environmental monitoring and biomonitoring of contaminant metals; controlling for sources of exposure, and developing clinical interventions that remove metals or weaken their effects on the body.

Gervasio A. Lamas

“Large population studies indicate that even low-level exposure to contaminant metals is near-universal and contributes to the burden of cardiovascular disease, especially heart attacks, stroke, disease of the arteries to the legs, and premature death from cardiac causes,” said Gervasio A. Lamas, M.D., FAHA, chair of the statement writing group and chairman of medicine and chief of the Columbia University Division of Cardiology at Mount Sinai Medical Center in Miami Beach, Florida.

“These metals interfere with essential biological functions and affect most populations on a global scale,” said vice chair of the statement writing group Ana Navas-Acien, M.D., Ph.D., a professor of environmental health sciences at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health and director of the Columbia University Northern Plains Superfund Research Programme in New York City. “After exposure, lead and cadmium accumulate in the body and can be found in bones and organs for decades. According to one large study, lead exposure may be responsible for more than 450,000 deaths in the United States alone.”

Where are people exposed to contaminant metals?

Most contaminant metal exposure occurs unintentionally, through daily activities. Lead can be found in a wide range of products, including paint in older homes (lead paint was banned in the United States in 1978), tobacco products, second-hand smoke, contaminated foods (ground water and some pottery, ceramics, and kitchenware are sources of lead contamination in food), water pipes, spices, cosmetics, electronics, and industrial emissions. Cigarette smoking contains both lead and cadmium.

Cadmium can be found in nickel-cadmium batteries, pigments, plastics, ceramics and glassware, and building materials. Industrial fertilisers contain cadmium-rich phosphate rock, which contaminates root vegetables and leafy green plants (including tobacco).

Arsenic exposure is primarily through groundwater, which affects drinking water, soil and food grown in contaminated soil. Notably, arsenic builds up in rice more than other food crops.

According to the statement, while exposure and risk occur across diverse populations regardless of socioeconomic level, some people are more exposed to toxic metals than others. People who live near major highways, industrial sources, and hazardous waste sites are at a higher risk of exposure, as are those who live in older homes or in areas where environmental regulations are poorly enforced and responses to community complaints are inadequate.

“This is a global issue in which lower-income communities are disproportionately exposed to toxic metals through contaminated air, water, and soil,” Navas-Acien explained. “Addressing metal exposure in these populations may provide a strategy to reduce cardiovascular disease disparities and advance environmental justice.”

What are the cardiovascular risks of contaminant metals?

The scientific statement outlines global epidemiologic research confirming that lead, cadmium and arsenic are associated with premature death, due in large part to increased cardiovascular disease risk. The global research includes:

- A 2021 American Heart Association scientific statement recognized exposure to toxic metals as a non-conventional risk factor for peripheral artery disease.

- A 2018 review published in the British Medical Journal assessed 37 studies representing nearly 350,000 people from more than a dozen countries. The review reported that higher urine levels of arsenic and blood levels of lead and cadmium were associated with 15%-85% higher risk for stroke and heart disease.

- One study in China found that higher levels of lead in the blood were associated with carotid plaque in people with Type 2 diabetes. Another found that cadmium and arsenic were associated with a higher rate of heart disease and ischemic stroke.

- In Spain, a general population study found that cadmium in urine was associated with increased rates of newly diagnosed cardiovascular disease.

What can be done about metals in the environment?

Monitoring environmental metal levels and testing for metal in individuals, according to the writing group, are critical steps in implementing appropriate public health initiatives. Health professionals use blood tests to monitor lead levels in children who exhibit symptoms of exposure. However, aside from those required for specific types of work, no monitoring guidelines or exposure limits for contaminant metals in adults have been established. Future research is needed to determine whether such testing can be used to identify and protect people at risk of cardiovascular disease.

Metal exposure can be reduced by reducing metal exposure in tobacco, protecting community water systems and wells, and minimising metal contamination in air, food, and soil, according to the statement’s authors.

“Cardiovascular health may be improved with a multi-pronged approach that recognises environmental cardiology and includes environmental monitoring and biomonitoring of contaminant metals; controlling for sources of exposure; and developing clinical interventions that remove metals or weaken their effects on the body,” said Lamas, a professor of medicine at Columbia University Irving Medical Centre in New York City.