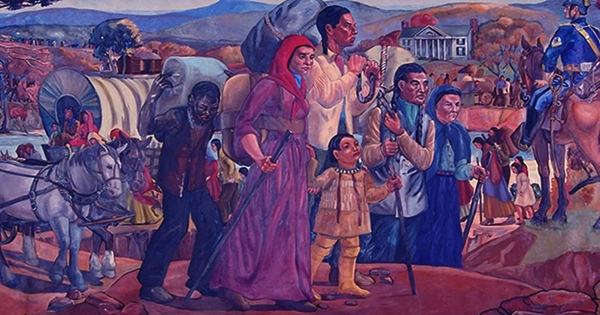

John Ross, the Cherokee nation’s longest-serving chief, spent much of his life fighting against his people’s forced relocation from their homelands. Tragically, he did so at a time when the United States government saw Native Americans as nothing more than a stumbling block to the new nation’s relentless westward development.

Ross rose to power amid Cherokee history’s most promising moment. They created a new capital city, formed their written language, and drafted a constitution throughout the 1820s. However, his reign as chief (1828-1866) coincided with the tribe’s most turbulent period, during which he faced tremendous pressure to cede their enormous ancestral area in the fertile Southeast. Beginning in 1827, Georgia began annexing Cherokee territories and claimed legal control. The Indian Removal Act, enacted in 1830, codified the federal government’s goal to relocate all indigenous people west of the Mississippi River. In 1835, a splinter group of Cherokees—including a former close adviser to Ross—signed an invalid treaty, which the federal government used to legitimize the Cherokees’ forced relocation, subsequently known as the Trail of Tears.

Ross, who is fluent in English and Cherokee, has long functioned as the tribe’s ambassador and negotiator. Toward the Setting Sun: John Ross, the Cherokees, and the Trail of Tears author Brian Hicks writes that Ross was “adept at citing both federal law and details from a dozen treaties the Cherokees signed with the federal government between 1785 and 1819.” When he became chief, the stakes for his Washington, D.C. missions skyrocketed. He fought Georgia’s assault on Cherokee sovereignty to the United States Supreme Court. And he struggled for two years, in multiple White House meetings with President Andrew Jackson, to overturn the unofficial pact. Even after his efforts failed and the tribe was compelled to march to Oklahoma territory, Ross assisted the remaining Cherokee in rebuilding. He continued to fight for their rights for the next quarter-century.

John Ross’ Early Years

Ross was born in Turkeytown, Alabama, to a Scottish father and a Cherokee mother in 1790. Turkeytown was previously part of the huge 43,000-square-mile Cherokee domain. Ross, known as Tsan-Usdi (Little John), was nurtured by his mother and grandmother in Cherokee matrilineal society. He witnessed European immigrants breaking federal treaties by establishing on Cherokee grounds while working at his paternal grandfather’s trade station. As a young man, he became committed to defending the rights of his mother’s people.

The Cherokee were deemed one of the five “civilized tribes” by Americans because they had acquired features of European civilization such as Christianity, the concept of personal wealth, intermarriage with non-Indians—and the practice of owning enslaved people as a show of economic status. The Cherokee established New Echota as their capital city, complete with schools, churches, and a courthouse. They drafted their charter. They also reached an unusual degree of tribal literacy by developing their writing system and publishing the Cherokee Phoenix newspaper in their native language in 1828.

Ross was nurtured in Cherokee ways but was also thoroughly assimilated. Instead of traditional Cherokee attire, he donned suits and ties. He attended Kingston Academy in Tennessee for his education. According to Bernard Vincent, author of “Slaveholding Indians: The Case of the Cherokee Nation,” Ross not only ran his family’s profitable trading center, but he also became a wealthy planter with 170 acres and 19 enslaved workers. He even joined the enigmatic Freemasons.

Cherokees Back Andrew Jackson During the Creek War

Civil war broke out among adjacent Creek Indians in 1813, with the British and Americans, as well as other tribal groupings, on opposing sides. During the conflict, Ross fought alongside hundreds of Cherokee warriors alongside US General Andrew Jackson. Cherokee assistance was critical during the Battle of Horseshoe Bend, which shifted the tide of the Creek War in favor of the Americans. Jackson rose to notoriety as a war hero, an image he exploited.

Years later, Cherokee Chief Junaluska reflected on his role in Jackson’s achievement, saying, “If I had known Jackson would drive us from our homes, I would have killed him that day at the Horse Shoe.” In the next years, Ross and Jackson would also clash.

Ross’ Rise to Prominence

Ross’s background in Cherokee territory, as well as his extensive understanding of previous treaties, qualified him to be an advocate. Following the Creek War, Ross accompanied a delegation in 1816 to protest Andrew Jackson’s proposal to capture 23 million acres of Indian territory under the Treaty of Fort Jackson. They were successful in persuading Secretary of War William H. Crawford of the merits of their case, which enraged Jackson.

“He [Jackson] was naturally no friend to the Indians, though he did not hesitate to accept favors from them when the occasion arose, and his determination to rid the southern states of them was strengthened by his temporary embarrassment and humiliation,” historian Rachel Caroline Eaton wrote in her book John Ross and the Cherokee Indians.

From 1819 to 1826, Ross was president of the Cherokee Nation Council, during which time state commissioners attempted to bribe him into selling Cherokee territory. While resisting these incursions, he was imprisoned and lost his home.

Ross was appointed senior chief of the Cherokee Nation in New Echota, Georgia, in 1828. His close aide, legendary warrior Major Ridge, was designated an official counselor.

Cherokee Land Battles Heat Up

Ross devoted most of his time and energy to opposing the Indian Removal Act.

Since 1817, Andrew Jackson had advocated for Indian deportation across the Mississippi River, persuading some Cherokees to join him. But Ross fought back, representing around 16,000 people who refused to leave. The Cherokee Council declared in 1822 that the country would not sell another acre of territory. By 1825, New Echota had a courthouse, council house, and public square.

The Cherokee expelled unlawful squatters from their lands in February 1830, amid heated arguments in Congress over Indian removal, and Major Ridge led a raid that burnt white settlers’ dwellings. Three months later, Congress passed the Indian Removal Act, paving the way for the forced displacement of Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, and Creek Indians to the western frontier in 1838 and 1839.

In a letter to Congress two years later, Jackson, who became president in 1828, asked for Indian removal:

“What good man would prefer a country covered with forests and ranged by a few thousand savages to our extensive Republic, studded with cities, towns, and prosperous farms embellished with all the improvements which art can devise or industry execute, occupied by more than 12,000,000 happy people, and filled with all the blessings of liberty, civilization, and religion?”

Treaty of New Echota

Because of the existence of a Cherokee constitution, the state of Georgia passed legislation eroding its sovereignty and annexing Cherokee territories. Ross carried his Georgia battle to Washington, D.C., and won: the Supreme Court ruled against the extension of state law to Cherokee territory.

Major Ridge’s son John, according to Hicks, lost faith in the federal government’s ability to enforce the verdict and urged his father to relocate. By 1833, the Cherokees were divided over removal, with Ross and Major Ridge on opposing sides. In 1835, a small number of Cherokees signed the Treaty of New Echota, promising to relocate to Oklahoma in exchange for $5 million and new land.

Ross had requested $20 million in his negotiations with President Jackson.

“We can never forget these homes, I know,” Major Ridge said, “but an unbending, iron necessity tells us we must leave them… There is only one way to safety, only one way to a Nation’s future survival.”

Ross attempted but failed to reverse it. In a letter to the United States Congress and Senate, he emphasized the negative consequences: “We are stripped of every attribute of freedom and eligibility for legal self-defense.” Our property may be robbed in front of our eyes; violence may be committed against us; and even our lives may be taken away, with no regard for our concerns. We have been denationalized and disenfranchised… We don’t have any land or a place to live.”

In May 1838, the United States Army herded up over 16,000 Cherokee into holding cages, shooting those who tried to run. The soldiers sent to “guard” the detained families subjected them to disease, malnutrition, and sexual assault. An estimated 3,000 to 4,000 Cherokees died on the 1,000-mile-long Trail of Tears to Oklahoma Territory that summer and winter. Ross, defeated, would follow and serve as their chief for the remainder of his life, including the Civil War.

Lingering Divisions Among the Cherokee

Cherokee tribal schisms over the contentious Treaty of New Echota continue to this day. According to tribal historian Catherine Gray Foreman, this derives from the nation’s prohibition on further land concessions in 1819. Three of the thirty men who signed the treaty were executed for breaching that statute on the same day in 1839: Cherokee Phoenix publisher Elias Boudinot, Major Ridge, and Ridge’s son John.

“John Ridge was dragged from his horse and stabbed in front of his children,” Foreman, who is a direct descendent of New Echota Treaty signer James Star, Sr., said. “This division is something Cherokees get very emotional about to this day.”

According to Foreman, John Ross is regarded as the Cherokee’s longest-serving major chief and a determined hero of tribal sovereignty and unity.

“He saw us through some dark times,” Foreman remarked. “And by establishing a constitutional government.” He negotiated a treaty with the federal government on his deathbed in 1866, which is credited with keeping the Cherokee Nation intact.”