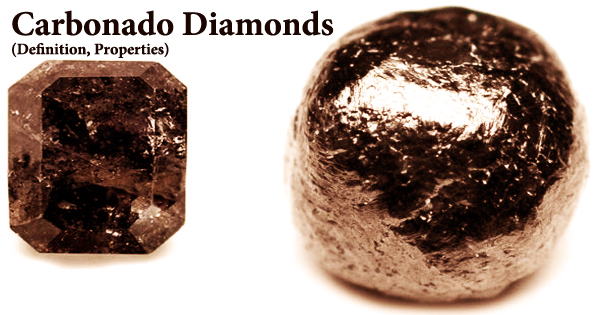

Carbonado, also called as “black diamond,” looks like charcoal and is named after the Portuguese word for “burned.” It is one of the most difficult natural diamonds to work with. It’s an impure, high-density, micro-porous type of polycrystalline diamond made up of diamond, graphite, and amorphous carbon, with tiny crystalline precipitates filling pores and reduced metal inclusions on occasion. This diamond is a rare and unique industrial diamond type. They’re virtually entirely made up of microcrystalline diamonds arranged in a random crystallographic pattern.

Only Brazil and the Central African Republic have carbonado diamonds. Unlike any typical diamond from kimberlites-lamproites, crustal collisional settings, or meteorite impact, these unique diamond aggregates are firmly connected and porous, with melt-like glassy patinas. It has a black or dark grey natural color and is more porous than other diamonds. They don’t appear like any other form of diamond when found in the field. They’re black, opaque, porous, and have a slight shine to them.

Carbonado diamonds were originally identified as a diamond kind in 1841 by Portuguese prospectors in Brazil, who named them “carbonado” because they resemble small bits of charcoal. They are porous aggregates of numerous small black crystals that are pea-sized or bigger. Carbonados are produced in the Central African Republic and Brazil, none of which is connected with kimberlite, the mineral that produces conventional gem diamonds.

In many cutting and grinding applications, carbonado diamonds outperform other kinds of industrial diamonds. When monocrystalline diamond abrasive granules break or split in the high-stress environment of cutting and grinding, the fracture or cleavage frequently spans the whole length of the diamond granule. Carbonado’s origins might be alien, which would explain some of its peculiar characteristics.

Carbonados, unlike diamonds, are never discovered in igneous kimberlite rock produced deep down. Carbonados crystallized around 3 billion years ago, according to lead isotope studies; nevertheless, carbonado is found in newer sedimentary strata. Rather, they’re found in alluvial and sedimentary deposits. Carbonado micro-diamonds (usually smaller than 20 microns or 20 millionths of a meter) do not include traces of minerals found deep in the Earth’s mantle, as do other diamonds.

Because carbonado granules are made up of a large number of interlocking diamond microcrystals, many fractures and cleaves will halt at a crystal boundary rather than spreading all the way through the granule. Mineral grains found in diamonds have been widely researched for clues to the diamond’s genesis. Inclusions of common mantle minerals like as pyrope and forsterite have been found in some normal diamonds, but these mantle minerals have not been found in carbonado.

The main host rock consistent with the formation of the conventional diamond at high temperatures and pressures has yet to be discovered nearly two centuries after carbonado’s discovery. Its origins have been modeled in a variety of ways, ranging from terrestrial subduction to cosmic sources. Some carbonados, on the other hand, contain authigenic inclusions of minerals found in the Earth’s crust; the inclusions do not necessarily establish the formation of diamonds in the crust, but they may have been introduced after carbonado formation because the obvious crystal inclusions occur in the pores that are common in carbonados.

The French valued carbonado as good polishing material. It was utilized for drilling during the Panama Canal construction and was part of the US strategic material stockpile until 1990. Carbonado is frequently referred to as a “black diamond,” although the term should only be applied to diamonds with a black body color generated by clouds of microscopic black inclusions or carbonization on fracture surfaces.

Carbonado emits bright luminescence (photoluminescence and cathodoluminescence) when nitrogen and vacancies in the crystal lattice are present. They do, however, have traces of nitrogen, hydrogen, and osbornite (a mineral otherwise found only in meteors). Radiation damage is thought to have happened after the creation of the carbonados, as evidenced by the presence of luminescence halos around radioactive inclusions. While previous research of carbonado concentrated on its physical and chemical characteristics and production, more recent studies have included dating methods, high-resolution microscopy, spectroscopy, and a focus on origin. Carbonado’s polycrystalline texture makes it more durable than a monocrystalline diamond.

It has the same hardness as regular diamonds, but it is far more durable. Because of its polycrystalline structure, a single abrasive granule can offer several crystallographic orientations of the diamond crystal at the cutting surface, with the hardest orientation cutting the most aggressively. Carbonado is available in five different sizes: >200 ct, 75–95 ct, 25–35 ct, 8–15 ct, and 0.25–1.25 ct. Sand-sized particles (less than 1 mm) have also been observed, as have melon-sized items bigger than the Sergio.

The presence of carbonado as a microcrystalline aggregate determines many of its characteristics. As a result, it lacks the typical octahedral, cubic, or dodecahedral crystal shapes found in other diamond types. Carbonados’ material source, according to proponents of an alien origin, was a supernova that happened at least 3.8 billion years ago. A huge mass crashed to Earth as a meteorite around 2.3 billion years ago after consolidating and floating through space for nearly one and a half billion years.

Within the microcrystalline aggregate, crystal formations are concealed. Because the crystals are interlocked and oriented in various crystallographic orientations, there is no cleavage or consistent hardness across the specimen. Carbonado can also have a pitted surface and a 10 percent or greater interior porosity. These characteristics are unusual for any diamond.

It may have fractured as it entered the Earth’s atmosphere, crashing into an area that would eventually split into Brazil and the Central African Republic, the only two known locations of carbonado deposits. When using carbonado as a scratching or cutting tool, the hardest microcrystal in contact with the scratched or sliced item determines the carbonado’s effective hardness. As a result, when compared to single-crystal diamond abrasives, carbonado can be tougher and have a greater apparent hardness.

Information Sources: