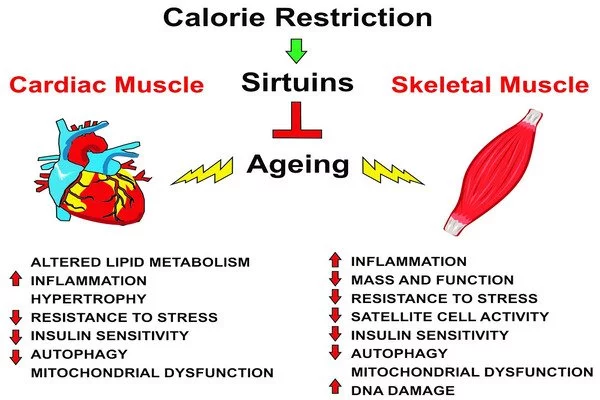

Calorie restriction, also known as caloric restriction (CR), is a dietary approach in which calories are reduced while necessary nutrients are maintained. It has been intensively examined in a variety of creatures, including humans, to better understand its possible impacts on aging and health.

According to researchers at the National Institutes of Health and their colleagues, reducing overall calorie intake may renew your muscles and activate biochemical pathways necessary for optimal health. Calorie restriction, or reducing calories without depriving the body of important vitamins and minerals, has long been known to slow the course of age-related disorders in animal models. According to a new study published in Aging Cell, the same molecular principles may apply to humans.

Researchers examined data from participants in the Comprehensive Assessment of Long-Term Effects of Reducing Intake of Energy (CALERIE), a study funded by the National Institute on Aging (NIA) that looked at whether moderate calorie restriction provided the same health benefits seen in animal studies. They discovered that during a two-year period, the goal for participants was to lower their daily caloric consumption by 25%, while the group’s best result was a 12% reduction. Nonetheless, this minor calorie reduction was sufficient to activate the majority of the cellular mechanisms involved in healthy aging.

A 12% reduction in calorie intake is very modest. This kind of small reduction in calorie intake is doable and may make a big difference in your health.

Luigi Ferrucci

“A 12% reduction in calorie intake is very modest,” said corresponding author and NIA Scientific Director Luigi Ferrucci, M.D., Ph.D. “This kind of small reduction in calorie intake is doable and may make a big difference in your health.”

The research team then tried to explore the molecular foundations of the benefits seen in prior, limited human calorie restriction research. According to one study, those on calorie restriction lost muscle mass and an average of 20 pounds in the first year and then maintained their weight for the next year. However, calorie restriction participants did not lose muscle strength despite losing muscle mass, showing that calorie restriction improved the amount of force generated by each unit of muscle mass, known as muscle-specific force.

For the current study, scientists examined thigh muscle biopsies taken from CALERIE participants when they first enrolled in the trial, as well as at one-year and two-year follow-ups.

The scientists obtained messenger RNA (mRNA), a molecule that encodes the code for proteins, from muscle samples to determine which human genes were altered by calorie restriction. The researchers analyzed the protein sequence of each mRNA and utilized this information to determine which genes produced particular mRNAs.

Further analysis assisted the scientists in determining which genes were upregulated during calorie restriction, indicating that the cells created more mRNA, and which were downregulated, indicating that the cells produced less mRNA. Calorie restriction influenced the same gene pathways in humans as it did in mice and non-human primates, according to the study. A lower caloric intake, for example, elevated genes involved in energy synthesis and metabolism while downregulating inflammatory genes, resulting in less inflammation.

“Since inflammation and aging are strongly coupled, calorie restriction represents a powerful approach to preventing the pro-inflammatory state that is developed by many older people,” said Ferrucci.