Bird Flu or Avian Flu, also called Avian Influenza, a viral respiratory disease mainly of poultry and certain other bird species, including migratory water-birds, some imported pet birds, and ostriches, that can be transmitted directly to humans. H5N1 is the most common form of bird flu. It’s deadly to birds and can easily affect humans and other animals that come in contact with a carrier. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), H5N1 was first discovered in humans in 1997 and has killed nearly 60 percent of those infected. The type with the greatest risk is highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI).

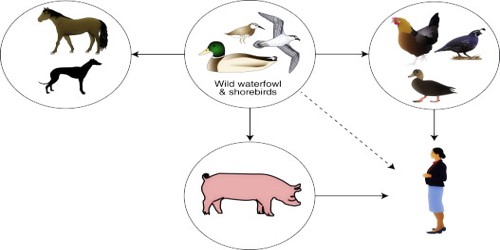

Bird flu is similar to swine flu, dog flu, horse flu and human flu as an illness caused by strains of influenza viruses that have adapted to a specific host. Out of the three types of influenza viruses (A, B, and C), influenza A virus is a zoonotic infection with a natural reservoir almost entirely in birds. Avian influenza, for most purposes, refers to the influenza A virus.

There are lots of different strains of the bird flu virus. Most of them don’t infect humans. But there are 4 strains that have caused concern in recent years:

- H5N1 (since 1997)

- H7N9 (since 2013)

- H5N6 (since 2014)

- H5N8 (since 2016)

Although H5N1, H7N9, and H5N6 don’t infect people easily and aren’t usually spread from human to human, several people have been infected around the world, leading to a number of deaths. H5N8 has not infected any humans worldwide to date.

The virus spreads through infected birds shedding the virus in their saliva, nasal secretions, and droppings. Healthy birds get infected when they come into contact with contaminated secretions or feces from infected birds. Contact with contaminated surfaces such as cages might also allow the virus to transfer from bird to bird. Symptoms in birds range from mild drops in egg production to failure of multiple major organs and death.

Between early 2013 and early 2017, 916 lab-confirmed human cases of H7N9 were reported to the World Health Organization (WHO). On 9 January 2017, the National Health and Family Planning Commission of China reported to WHO 106 cases of H7N9 which occurred from late November through late December, including 35 deaths, 2 potential cases of human-to-human transmission, and 80 of these 106 persons stating that they have visited live poultry markets. The cases are reported from Jiangsu (52), Zhejiang (21), Anhui (14), Guangdong (14), Shanghai (2), Fujian (2) and Hunan (1). Similar sudden increases in the number of human cases of H7N9 have occurred in previous years during December and January.

Risk Factors of Bird Flu: H5N1 has the ability to survive for extended periods of time. Birds infected with H5N1 continue to release the virus in feces and saliva for as long as 10 days. Touching contaminated surfaces can spread the infection.

People may have a greater risk of contracting H5N1 if they are:

- A poultry farmer

- A traveler visiting affected areas

- Exposed to infected birds

- Someone who eats undercooked poultry or eggs

- A healthcare worker caring for infected patients

- A household member of an infected person

Spreads to Humans: Bird Flu is most often spread by contact between infected and healthy birds, though can also be spread indirectly through contaminated equipment. The virus is found in secretions from the nostrils, mouth, and eyes of infected birds as well as their droppings. HPAI infection is spread to people often through direct contact with infected poultry, such as during slaughter or plucking. Though the virus can spread through airborne secretions, the disease itself is not an airborne disease. Highly pathogenic strains spread quickly among flocks and can destroy a flock within 28 hours; the less pathogenic strains may affect egg production but are much less deadly.

Bird flu is spread by close contact with an infected bird (dead or alive).

This includes:

- Touching infected birds

- Touching droppings or bedding

- Killing or preparing infected poultry for cooking

Markets, where live birds are sold, can also be a source of bird flu. Avoid visiting these markets if you’re traveling to countries that have had an outbreak of bird flu. You can’t catch bird flu through eating fully cooked poultry or eggs, even in areas with an outbreak of bird flu.

Although direct contact with sick poultry poses the highest risk for bird flu, indirect exposure to bird feces or other materials such as bird eggs is also a risk. Contact with unwashed eggs from sick birds or water contaminated by poultry feces poses a potential risk of disease.

Causes and Symptoms of Bird Flu: Bird flu in avian species occurs in two forms, one mild and the other highly virulent and contagious; the latter form is called fowl plague. Mutation of the virus causing the mild form is thought to have given rise to the virus causing the severe form. The virus that causes bird flu is influenza A type with eight RNA strands that make up its genome. Influenza viruses are further classified by analyzing two proteins on the surface of the virus. The proteins are called hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N). There are many different types of hemagglutinin and neuraminidase proteins. For example, the recent pathogenic bird flu virus has type 5 hemagglutinin and type 1 neuraminidase. Thus, it is named the “H5N1” influenza A virus (also termed HPAI or highly pathogenic avian influenza). The 2013 virus has different surface proteins, H7 and N9, hence the name H7N9. Other bird flu types include H7N7, H5N8, H5N2, and H9N2.

Genetic analysis suggests that the influenza A subtypes that afflict mainly nonavian animals, including humans, pigs, whales, and horses, derive at least partially from bird flu subtypes. H5N1 occurs naturally in wild waterfowl, but it can spread easily to domestic poultry. The disease is transmitted to humans through contact with infected bird feces, nasal secretions, or secretions from the mouth or eyes. Spreading of H5N1 from Asia to Europe is much more likely caused by both legal and illegal poultry trades than dispersing through wild bird migrations, being that in recent studies, there were no secondary rises in infection in Asia when wild birds migrate south again from their breeding grounds. Instead, the infection patterns followed transportation such as railroads, roads, and country borders, suggesting poultry trade as being much more likely. While there have been strains of avian flu to exist in the United States, they have been extinguished and have not been known to infect humans.

Consuming properly cooked poultry or eggs from infected birds doesn’t transmit the bird flu, but eggs should never be served runny. Meat is considered safe if it has been cooked to an internal temperature of 165ºF (73.9ºC).

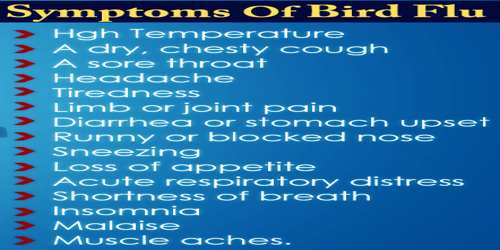

Bird Flu Symptoms – Bird flu symptoms in humans can vary and range from “typical” flu symptoms (fever, sore throat, muscle pain) to eye infections and pneumonia. The disease caused by the H5N1 virus is a particularly severe form of pneumonia that leads to viral pneumonia and multiorgan failure in many people who become infected.

The main symptoms of bird flu can appear very quickly and include:

- a very high temperature or feeling hot or shivery (above 38 C or 100.4 F)

- aching muscles

- headache

- a cough

Other early symptoms may include:

- diarrhoea

- sickness

- stomach pain

- chest pain

- bleeding from the nose and gums

- conjunctivitis

Within days of symptoms appearing, it’s possible to develop more severe complications such as pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome. Getting treatment quickly, using antiviral medicine, may prevent complications and reduce the risk of developing severe illness.

Diagnose Treatment, and Prevention of Bird Flu: Routine tests for human influenza A will be positive in patients with bird flu but are not specific for the avian virus. To make a specific diagnosis of bird flu, specialized tests are needed. In the United States, local health departments and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) can provide access to the specialized testing. The virus can be detected in sputum by several methods, including culture or polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Cultures should be done in laboratories that have an appropriate biosafety certification. PCR detects nucleic acid from the influenza A virus. Specialized PCR testing is available in reference laboratories to identify avian strains; the CDC is a primary source for available tests for the newest strains of bird flu and can identify the specific type of virus (for example, H5N1 or H7N9).

A doctor may also perform the following tests to look for the presence of the virus that causes bird flu:

- auscultation (a test that detects abnormal breath sounds)

- white blood cell differential

- nasopharyngeal culture

- chest X-ray

Additional tests can be done to assess the functioning of the patient’s heart, kidneys, and liver.

During and after infection with bird flu, the body makes antibodies against the virus. Blood tests can detect these antibodies, but this requires one sample at the onset of disease and another sample several weeks later. Thus, results are usually not available until the patient has recovered or died.

Patients may be given an antiviral medicine such as oseltamivir (Tamiflu) or zanamivir (Relenza) recommend by the CDC and the World Health Organization (WHO). Antiviral medicines help reduce the severity of the condition, prevent complications and improve the chances of survival. They are also sometimes given to people who have been in close contact with infected birds, or those who have had contact with infected people, for example family or healthcare staff.

The CDC suggests the best way to prevent bird flu is to avoid exposure whenever possible to birds and their feces. People are advised not to touch any ill-appearing or dead birds. Currently, there is no vaccine to protect against H7N9 types of bird flu.

The complications of bird flu are frequently dire and include:

- shortness of breath or difficulty breathing,

- pneumonia,

- acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS),

- abdominal pain,

- lung collapse,

- shock,

- altered mental status,

- seizures,

- organ system failure, and

- death.

Unfortunately, individuals who become infected with bird flu often have one or more complications listed above. The mortality (death) rate varies somewhat between strains with H5N1 at about 55%, and H7N9 at about 37%.

With proper infection control and the use of personal protective equipment (PPE), the chance for infection is low. Protecting the eyes, nose, mouth, and hands is important for prevention because these are the most common ways for the virus to enter the body. Appropriate personal protective equipment includes aprons or coveralls, gloves, boots or boot covers, and a headcover or hair cover. Disposable PPE is recommended. An N-95 respirator and unvented/indirectly vented safety goggles are also part of appropriate PPE. A powered air-purifying respirator (PAPR) with hood or helmet and face shield is also an option.

Things to do prevent Bird Flu – If anyone visiting a foreign country that’s had an outbreak they should:

- wash your hands often with warm water and soap, especially before and after handling food, in particular, raw poultry

- use different utensils for cooked and raw meat

- make sure meat is cooked until steaming hot

- avoid contact with live birds and poultry

What not to do:

- do not go near or touch bird droppings or sick or dead birds

- do not go to live animal markets or poultry farms

- do not bring any live birds or poultry back to the UK, including feathers

- do not eat undercooked or raw poultry or duck

- do not eat raw eggs

Prevention and control programs must take into account local understandings of people-poultry relations. In the past, programs that have focused on singular, place-based understandings of disease transmission have been ineffective. Prevention and control methods have been more effective when also considering the social, political, and ecological agents in play.

However, bird flu can be prevented by avoiding contact with sick poultry originating in countries known to be affected by the virus. Prevention also includes poultry-safety measures such as destroying flocks when sick birds are identified and vaccinating healthy flocks. Combined with import bans, this culling has effectively limited the spread of bird flu in outbreak situations but naturally has negative effects on the poultry and egg industry. Unlike SARS, which some investigators suggest has been eliminated from the world, or Ebola, which has a narrow geographic range (endemic in Africa), the bird flu continues to exist in significant areas of the world and can be spread widely by migrating birds. The poultry industry needs to follow the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) guidelines to protect their industry and workers from bird flu.

Bird Flu Vaccine Development: The seasonal flu vaccine doesn’t protect against bird flu. Because of the many immunologically distinct viral subtypes that cause influenza in animals and the ability of the virus to rapidly evolve new strains, the preparation of effective vaccines is complicated. The most effective control of outbreaks in poultry remains the rapid culling of infected farm populations and the decontamination of farms and equipment. This measure also serves to reduce the chances for human exposure to the virus.

In 2007 the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved a vaccine to protect humans against one subtype of the H5N1 virus. It was the first vaccine approved for use against bird flu in humans. Drug manufacturers and policymakers in developed and developing countries worked toward establishing a stockpile of the vaccine to provide some measure of protection against a future outbreak of bird flu. Vaccine side effects include a sore arm, fatigue, or temporary muscle aches. The vaccine has not been tested in large numbers of patients, however, and there may be other side effects that have not yet been detected. The current vaccine is effective against the strain that has caused the large outbreaks of bird flu, but it may not be as effective against a newly mutated strain found in 2011. Consequently, this vaccine seems unlikely to offer protection against the new H7N9 bird flu, but data is not available to date.

In addition, scientists worked to develop a vaccine that is effective against another subtype of H5N1, as well as a vaccine that might protect against all subtypes of H5N1. Studies suggest that antiviral drugs developed for human flu viruses would work against bird flu infection in humans. The H5N1 virus, however, appears to be resistant to at least two of the drugs, amantadine, and rimantadine.

Information Sources: