Bipolar disorder is distinguished by a combination of state-related changes in psychological function that are limited to illness episodes, as well as trait-related changes that persist throughout periods of remission, regardless of symptom status.

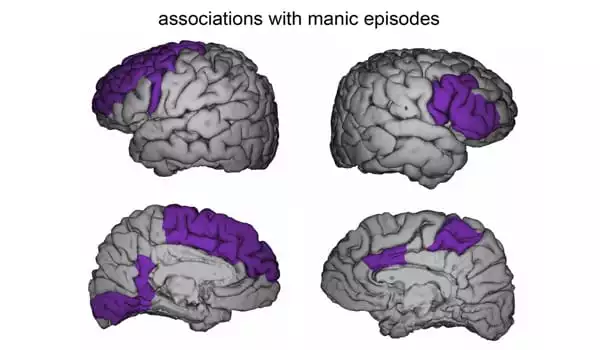

People with bipolar disorder who had frequent manic episodes had faster cortical thinning, particularly in the prefrontal cortex than those who had less frequent mania episodes. Researchers also discovered that those who experienced more frequent mania had faster ventricle enlargement and slower thinking in the parahippocampal and fusiform cortical regions.

According to one of the largest longitudinal brain imaging studies in its field to date, patients with bipolar disorder who experience manic episodes are more likely to show abnormal brain changes over time. The study, led by researchers from Sweden’s Karolinska Institutet and the University of Gothenburg, also confirms links between bipolar disorder and accelerated brain ventricle enlargement.

The findings are published online in the journal Biological Psychiatry.

Patients with bipolar disorder who experience manic episodes are more likely to show abnormal brain changes over time, according to one of the largest longitudinal brain imaging studies in its field to date.

Bipolar disorder is a psychiatric disorder distinguished by recurring episodes of mania and depression. Previous imaging studies on bipolar patients’ brains discovered structural abnormalities. These abnormalities include lower cortical thickness when compared to healthy people. The cortex, or the outer layer of the brain, naturally shrinks with age, but accelerated cortical thinning has been linked to a variety of brain diseases.

Most previous neuroimaging studies on bipolar disorder were small and cross-sectional in nature, capturing only one point in time. As a result, there has been a dearth of large-scale studies that have investigated brain changes over time.

The researchers overcame these limitations in this study by collecting magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) data from 14 research centers around the world and examining changes in the brain over a nine-year period. The study included 1,232 people, 307 bipolar disorder patients, and 925 healthy controls.

Changes in the prefrontal cortex

The researchers discovered a link between the number of manic episodes and the degree of cortical brain changes observed during the study period: While more manic episodes were associated with faster cortical thinning, patients who had no episodes showed no changes or even increased cortical thickness. These changes were most noticeable in the prefrontal cortex, which is important for emotion regulation, planning, decision-making, impulse control, and other cognitive functions.

“The fact that cortical thinning in patients is associated with manic episodes emphasizes the importance of treatment to prevent mood episodes and is important information for psychiatrists,” says Professor Mikael Landén of the University of Gothenburg’s Institute of Neuroscience and Physiology and the Department of Medical Epidemiology and Biostatistics at Karolinska Institutet.

“Researchers should concentrate on better understanding the progressive mechanisms at work in bipolar disorder in order to improve treatment options in the long run.” When bipolar disorder patients were compared to healthy individuals, the changes over time in three brain regions were significantly different: the ventricles – cavities that produce cerebrospinal fluid, which is important for brain protection and two areas linked to recognition and memory: the fusiform and parahippocampal cortex. While bipolar patients had faster ventricle enlargements than the control group, they had slower thinning of the fusiform and parahippocampal cortical regions on average.

Signs of neuro progressive disorder

“The abnormal ventricle enlargements, as well as the associations between cortical thinning and manic symptoms, suggest that bipolar disorder is a neuro progressive disorder, which could explain the worsening of bipolar symptoms in some patients,” says corresponding author Christoph Abé, a researcher at Karolinska Institutet’s Department of Clinical Neuroscience.

“In the future, it is critical to clarify this and identify the exact causes in order to prevent mood episodes and the impact they may have on the brain.” The researchers point out that the discovery of slower cortical thinning in some brain areas of bipolar patients could be explained by so-called flooring effects, as bipolar disorder patients typically have a lower cortical thickness, to begin with than healthy individuals.

Another possibility is that this finding reflects structural improvements as a result of treatment effects, such as the neuroprotective effects of lithium medication. As a result, the brain changes observed in this study may not reflect changes that occur during the natural course of bipolar disorder if left untreated.

The ENIGMA Bipolar Disorder Working Group, a large international multi-center team of more than 70 researchers, was involved in the study.