The Partition of Bengal (1905), also well known as ‘Bang-Bhang’ (Bengali: বঙ্গভঙ্গ) was a territorial reorganization of the Bengal Presidency implemented by the authorities of the British Raj in 1905. The partition separated the largely Muslim eastern areas from the largely Hindu western areas on 16th October 1905 after being announced on 19th July 1905 by the then Viceroy of India, Lord Curzon.

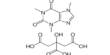

(Lord Curzon)

According to Lord Curzon, the Partition of Bengal was done due to some administrative reasons but Indians believed that it was a result of ‘Divide and Rule’ policy of The British Government.

Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa had formed a single province of British India since 1765. By 1900 the province had grown too large to handle under a single administration. East Bengal, because of isolation and poor communications, had been neglected in favour of west Bengal and Bihar. Curzon chose one of several schemes for partition: to unite Assam, which had been a part of the province until 1874, with 15 districts of east Bengal and thus form a new province with a population of 31 million. The capital was Dacca (now Dhaka, Bangl.), and the people were mainly Muslim.

The Hindus of West Bengal, who dominated Bengal’s business and rural life, complained that the division would make them a minority in a province that would incorporate the province of Bihar and Orissa. Hindus were outraged at what they saw as a “divide and rule” policy (where the colonisers turned the native population against itself in order to rule), even though Curzon stressed it would produce administrative efficiency. The partition animated the Muslims to form their own national organization on communal lines. In order to appease Bengali sentiment, Bengal was reunited by Lord Hardinge in 1911, in response to the Swadeshi movement’s riots in protest against the policy and the growing belief among Hindus that east Bengal would have its own courts and policies.

The lieutenant governor of Bengal had to administer an area of 189,000 sq miles and by 1903 the population of the province had risen to 78.50 million. Consequently, many districts in eastern Bengal had been practically neglected because of isolation and poor communication which made good governance almost impossible. Calcutta and its nearby districts attracted all the energy and attention of the government. The condition of peasants was miserable under the exaction of absentee landlords; and trade, commerce and education were being impaired. The administrative machinery of the province was under-staffed. Especially in east Bengal, in countryside so cut off by rivers and creeks, no special attention had been paid to the peculiar difficulties of police work till the last decade of the 19th century. Organized piracy in the waterways had existed for at least a century.

It is already clear that the Bengal was covering a vast area and was a place for a very large population of British India. The province was lacking advancement of education, infrastructure, industrial development and the problem of unemployment.

The British Government said that the Bengal was too large to be administered single-handedly and the eastern Bengal was less prosperous than the western Bengal. Also one of the reasons that Curzon described was that he wanted to separate the Bengalis from other native Indians.

The Indians and especially Hindu was not in the support of the partition of Bengal. According to them, the partition of Bengal was just a policy of the British Government to separate Hindu and Muslim of British India. They wanted to make Bengal a Muslim majority state and with the development of the state, they would achieve the trusts of Indian Muslims and their support. Indian Hindus called it a part of ‘Divide and Rule’ policy of the British Government.

The enlarged scheme received the assent of the governments of Assam and Bengal. The new province would consist of the state of Hill Tripura, the Divisions of Chittagong, Dhaka and Rajshahi (excluding Darjeeling) and the district of Malda amalgamated with Assam. Bengal was to surrender not only these large territories on the east but also to cede to the Central Provinces the five Hindi-speaking states. On the west it would gain Sambalpur and a minor tract of five Uriya-speaking states from the Central Provinces. Bengal would be left with an area of 141,580 sq. miles and a population of 54 million, of which 42 million would be Hindus and 9 million Muslims.

The new province was to be called ‘Eastern Bengal and Assam’ with its capital at Dhaka and subsidiary headquarters at Chittagong. It would cover an area of 106,540 sq. miles with a population of 31 million comprising 18 million Muslims and 12 million Hindus. Its administration would consist of a Legislative Council, a Board of Revenue of two members, and the jurisdiction of the Calcutta High Court would be left undisturbed. The government pointed out that the new province would have a clearly demarcated western boundary and well defined geographical, ethnological, linguistic and social characteristics. The most striking feature of the new province was that it would concentrate within its own bounds the hitherto ignored and neglected typical homogenous Muslim population of Bengal. Besides, the whole of the tea industry (except Darjeeling), and the greater portion of the jute growing area would be brought under a single administration. The government of India promulgated their final decision in a Resolution dated 19 July 1905 and the Partition of Bengal was effected on 16 October of the same year.

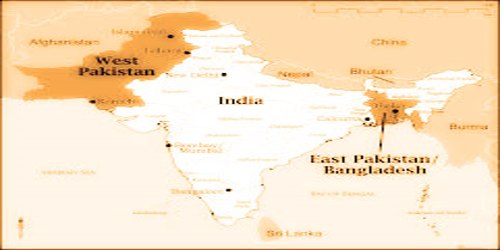

The partition divided Bengal into two provinces. The first one was Bengal including West Bengal, Orissa and Bihar and the second was East Bengal and Assam. The East Bengal had its capital Dhaka while the West Bengal had the Capital Calcutta. West Bengal was declared as the state with Hindu majority while the East Bengal was a state having the majority of Muslims.

In 1911, the year that the capital was shifted from Calcutta (now Kolkata) to Delhi, east and west Bengal were reunited; Assam again became a chief commissionership, while Bihar and Orissa were separated to form a new province. The aim was to combine appeasement of Bengali sentiment with administrative convenience. This end was achieved for a time, but the Bengali Muslims, having benefitted from partition, were angry and disappointed. This resentment remained throughout the rest of the British period. The final division of Bengal at the partitioning of the subcontinent in 1947, which split Bengal into India in the west and East Pakistan (later Bangladesh) in the east, was accompanied by intense violence.

The partition of Bengal created a sense of resentment among the people of India and especially among the Hindu of British India. Widespread political unrest was created and Indian National Congress protested against the step of the British Government of creating a communal line between the people of India. Although the partition was in the favour of Muslims as they had given a separate province so Muslims of India stood beside the British Government and praised him.

The Swadeshi Movement as an economic movement would have been quite acceptable to the Muslims, but as the movement was used as a weapon against the partition (which the greater body of the Muslims supported) and as it often had a religious colouring added to it, it antagonised Muslim minds.

The new tide of national sentiment in Bengal against the Partition spilled over into different regions in India- Punjab, Central Provinces, Poona, Madras, Bombay and other cities. Instead of wearing foreign made outfits, the Indians vowed to use only swadeshi (indigenous) cottons and other clothing materials made in India. Foreign garments were viewed as hateful imports. The Swadeshi Movement soon stimulated local enterprise in many areas; from Indian cotton mills to match factories, glassblowing shops, iron and steel foundries. The agitation also generated increased demands for national education. Bengali teachers and students extended their boycott of British goods to English schools and college classrooms. The movement for national education spread throughout Bengal and reached even as far as Benaras where Pandit Madan Mohan Malaviya founded his private Benaras Hindu University in 1910.

Prominent Bengali writer Rabindra Nath Tagore wrote ‘Amar Sonar Bangla’ during this period for the enlightenment of the Indians to rise and struggle against the immoral partition of the sacred land of Bengal.

The authorities not able to end the protest, assented to reversing the partition and did so in 1911. King George announced in December 1911 that eastern Bengal would be assimilated into the Bengal Presidency. Districts where Bengali was spoken were once again unified, and Assam, Bihar and Orissa were separated. The capital was shifted to New Delhi, clearly intended to provide the British Empire with a stronger base. Muslims of Bengal were shocked because they had seen the Muslim majority eastern Bengal as an indicator of the government’s enthusiasm for protecting Muslim interests. They saw this as the government compromising Muslim interests for Hindu protests and administrative ease.

The partition had not initially been supported by Muslim leaders. After the Muslim majority province of Eastern Bengal and Assam had been created prominent Muslims started seeing it as advantageous. Muslims, especially in Eastern Bengal, had been backward in the period of United Bengal. The Hindu protest against the partition was seen as interference in a Muslim province. With the move of the capital to a Mughal site, the British tried to satisfy Bengali Muslims who were disappointed with losing hold of eastern Bengal.

The Partition of Bengal affected the people of India in such a way that could never be altered again. Although the partition could last for only half decades, it created a major communal difference between the Hindu and Muslims of British India. The partition led an idea of creating a separate Muslim Political Party called All India Muslim League. It also gave an idea to Muslims to demand a separate nation ‘Pakistan’.

Lord Charles Hardinge succeeded Minto in 1910 and on 25 August 1911 in a secret despatch the government of India recommended certain changes in the administration of India. According to the suggestion of the Governor-General-in-Council, King George V at his Coronation Darbar in Delhi in December 1911 announced the revocation of the Partition of Bengal and of certain changes in the administration of India. Firstly, the Government of India should have its seat at Delhi instead of Calcutta. By shifting the capital to the site of past Muslim glory, the British hoped to placate Bengal’s Muslim community now aggrieved at the loss of provincial power and privilege in eastern Bengal. Secondly, the five Bengali speaking Divisions viz The Presidency, Burdwan, Dacca, Rajshahi and Chittagong were to be united and formed into a Presidency to be administered by a Governor-in-Council. The area of this province would be approximately 70,000 sq miles with a population of 42 million. Thirdly, a Lieutenant-Governor-in-Council with a Legislative Council was to govern the province comprising of Bihar, Chhota Nagpur and Orissa. Fourthly, Assam was to revert back to the rule of a Chief Commissioner. The date chosen for the formal ending of the partition and reunification of Bengal was I April 1912.

Despite its union in 1911, the Bengal went through another partition on 20th July 1947. It was not temporary like the earlier one and this time the Bengal was divided according to some pre-decided criteria.

The Bengal was divided into two parts as East Bengal and West Bengal. West Bengal was a Hindu majority province while the East Bengal had the majority of Muslims. The East Bengal was later joined to Pakistan on 14th August 1947 and was called East Pakistan. In 1971, because of some conflicts with Pakistan Government, East Bengal struggled and separated itself from ‘Pakistan’ and created a new republic nation called ‘Bangladesh’ (Independent State) and adopted ‘Amar Sonar Bangla’ as its national anthem.

Information Sources: