Biography of William Wilberforce

William Wilberforce – English politician, philanthropist.

Name: William Wilberforce

Date of Birth: 24 August 1759

Place of Birth: Kingston upon Hull, Great Britain

Date of Death: 29 July 1833 (aged 73)

Place of Death: Cadogan Place, London, United Kingdom

Father: Robert Wilberforce (1728–1768)

Mother: Elizabeth Bird (1730–1798)

Spouse: Barbara Wilberforce (m. 1797–1833)

Children: Samuel Wilberforce, Robert Wilberforce, Henry Wilberforce, William Wilberforce

Early Life

William Wilberforce (British politician and philanthropist), was born on 24 August 1759 in Hull, the son of a wealthy merchant. A native of Kingston upon Hull, Yorkshire, he began his political career in 1780, eventually becoming a Member of Parliament for Yorkshire (1784–1812). He was independent of party. In 1785, he became an evangelical Christian, which resulted in major changes to his lifestyle and a lifelong concern for social reform and progress. He was educated at St. John’s College, Cambridge.

Wilberforce was convinced of the importance of religion, morality, and education. He championed causes and campaigns such as the Society for the Suppression of Vice, British missionary work in India, the creation of a free colony in Sierra Leone, the foundation of the Church Mission Society, and the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. His underlying conservatism led him to support politically and socially controversial legislation and resulted in criticism that he was ignoring injustices at home while campaigning for the enslaved abroad.

In 1787, Wilberforce first came into contact with anti-slave trade activist. Initially sceptical of his abilities, he soon took on the campaign and introduced the abolition of slave trade in the House of Commons. And rest as they say is history. Despite repeated failures, he made constant attempts arguing against the injustice meted out to slaves and raising awareness about their pitiable conditions. It was due to his resilient approach that in the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act 1807 was finally passed.

All through his life, Wilberforce contributed significantly to reshaping the political and social scenario by promoting social responsibility and action. Till the end, he fought for slave right and merely three days before his death, witnessed the passing of the Abolition of Slavery Bill in the House of Commons. A month after his death, the Bill was passed in the House of Lords and became Abolition of Slavery Act.

In later years, Wilberforce supported the campaign for the complete abolition of slavery, and continued his involvement after 1826, when he resigned from Parliament because of his failing health. That campaign led to the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833, which abolished slavery in most of the British Empire. Wilberforce died just three days after hearing that the passage of the Act through Parliament was assured. He was buried in Westminster Abbey, close to his friend William Pitt the Younger.

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

William Wilberforce was born on August 24, 1759, as the only son of Robert Wilberforce (1728–1768), a wealthy merchant, and his wife, Elizabeth Bird (1730–1798), in a house on the High Street of Hull, in the East Riding of Yorkshire, England. His grandfather, William (1690–1774 or 1776), had made the family fortune in the maritime trade with Baltic countries and had twice been elected mayor of Hull.

Wilberforce gained his early education from Hull Grammar School. Upon his father’s death in 1768, Wilberforce was put under the guardianship of his uncle and aunt under whose influence he leaned towards evangelicalism. Returning to Hull in 1771, he resumed his studies. The religious fervor subsided as he engaged himself in social outings and led a hedonistic lifestyle.

He studied at St. John’s College at the University of Cambridge, where he became a close friend of the future prime minister William Pitt the Younger and was known as an amiable companion rather than an outstanding student. In 1780 both he and Pitt entered the House of Commons, and he soon began to support parliamentary reform and Roman Catholic political emancipation, acquiring a reputation for radicalism that later embarrassed him, especially during the French Revolution, when he was chosen an honorary citizen of France (September 1792). From 1815 he upheld the Corn Laws (tariffs on imported grain) and repressive measures against working-class agitation.

Despite his lifestyle and lack of interest in studying, he managed to pass his examinations and was awarded a B.A. in 1781 and an M.A. in 1788.

Personal Life

In his youth, William Wilberforce showed little interest in women, but when he was in his late thirties his friend Thomas Babington recommended twenty-year-old Barbara Ann Spooner (1777–1847) as a potential bride. Wilberforce met her two days later on 15 April 1797, and was immediately smitten; following an eight-day whirlwind romance, he proposed.

He married Barbara Ann Spooner, an evangelical Christian on May 30, 1797. Throughout, their marriage, the couple remained loyal and supportive of each other. They had six children in fewer than ten years: William (b. 1798), Barbara (b. 1799), Elizabeth (b. 1801), Robert Isaac Wilberforce (b. 1802), Samuel Wilberforce (b. 1805) and Henry William Wilberforce (b. 1807). Wilberforce was an indulgent and adoring father who revealed in his time at home and at play with his children.

Wilberforce was weak as a child with poor eyesight. His bad health troubled him all through his life. During the last years, he became gravely ill. His eyesight was also failing.

Career and Works

William Wilberforce began to consider a political career while still at university, and during the winter of 1779–1780, he and Pitt frequently watched House of Commons debates from the gallery. Pitt, already set on a political career, encouraged Wilberforce to join him in obtaining a parliamentary seat. In September 1780, at the age of twenty-one and while still a student, Wilberforce was elected Member of Parliament (MP) for Kingston upon Hull, spending over £8,000, as was the custom of the time, to ensure he received the necessary votes.

As an MP, Wilberforce served as a ‘no party man’. Wilberforce supported both the Tory and Whig government, mostly working in favor of the party in power. Due to the same, he was criticized by fellow politicians for his inconsistency. Blessed with excellent oratory skills, he gained a reputation for himself as an influential speaker with a sharp sense of wit. He became a renowned name in the political circle, due to his eloquence and fluency.

During the 1784 general election, Wilberforce stood as the candidate for the county of Yorkshire. On April 6, 1784, he returned to the House of Commons as the MP for Yorkshire. Wilberforce’s abolitionism was derived in part from evangelical Christianity, to which he was converted in 1784–85. His spiritual adviser became John Newton, a former slave trader who had repented and who had been the pastor at Wilberforce’s church when he was a child.

In October 1784, Wilberforce embarked upon a tour of Europe which would ultimately change his life and determine his future career. He traveled with his mother and sister in the company of Isaac Milner, the brilliant younger brother of his former headmaster, who had been Fellow of Queens’ College, Cambridge, in the year when Wilberforce first went up. They visited the French Riviera and enjoyed the usual pastimes of dinners, cards, and gambling. In February 1785, Wilberforce returned to London temporarily, to support Pitt’s proposals for parliamentary reforms. He rejoined the party in Genoa, Italy, from where they continued their tour to Switzerland. Milner accompanied Wilberforce to England, and on the journey, they read The Rise and Progress of Religion in the Soul by Philip Doddridge, a leading early 18th-century English nonconformist.

In 1787 Wilberforce helped to found a society for the “reformation of manners” called the Proclamation Society (to suppress the publication of obscenity) and the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade the latter more commonly called the Anti-Slavery Society. He and his associates Thomas Clarkson, Granville Sharp, Henry Thornton, Charles Grant, Edward James Eliot, Zachary Macaulay, and James Stephen were first called the Saints and afterward (from 1797) the Clapham Sect, of which Wilberforce was the acknowledged leader.

In 1786, Wilberforce leased a house in Old Palace Yard, Westminster, in order to be near Parliament. He began using his parliamentary position to advocate reform by introducing a Registration Bill, proposing limited changes to parliamentary election procedures. He brought forward a bill to extend the measure permitting the dissection after execution of criminals such as rapists, arsonists, and thieves. The bill also advocated the reduction of sentences for women convicted of treason, a crime that at the time included a husband’s murder. The House of Commons passed both bills, but they were defeated in the House of Lords.

In the House of Commons, Wilberforce was an eloquent and indefatigable sponsor of antislavery legislation. In 1789 he introduced 12 resolutions against the slave trade and gave what many newspapers at the time considered among the most eloquent speeches ever delivered in the Commons. The resolutions were supported by Pitt (who was by then prime minister), Charles Fox (often an opponent of Pitt’s), and Edmund Burke, but they failed to be enacted into law, and instead, the issue was postponed until the next session of Parliament.

Before introducing the subject of the abolition of slave trade in Parliament, he equipped himself with wide information regarding the subject. It was during this time that he befriended a Cambridge alumnus, Thomas Clarkson, a friendship that was to last for nearly half a century.

Clarkson had a major influence on Wilberforce. He provided the latter with first-hand evidence on the slave trade in England. Wilberforce was appalled by the working and living condition of slaves. On March 1787, he agreed to bring forward the abolition of the slave trade in the parliament.

Wilberforce’s involvement in the abolition movement was motivated by a desire to put his Christian principles into action and to serve God in public life. He and other evangelicals were horrified by what they perceived was a depraved and un-Christian trade and the greed and avarice of the owners and traders. Wilberforce sensed a call from God, writing in a journal entry in 1787 that “God Almighty has set before me two great objects, the suppression of the Slave Trade and the Reformation of Manners”. The conspicuous involvement of evangelicals in the highly popular anti-slavery movement served to improve the status of a group otherwise associated with the less popular campaigns against vice and immorality.

On May 12, 1789, Wilberforce made his first speech on the subject of abolition in the House of Commons. He zealously argued the state of slaves and the appalling condition in which they were brought from Africa. In his speech, he made 12 resolutions that condemned the slave trade but not slavery. His speech was rejected by the opposition who fiercely spoke against the motion.

In 1791 he again brought a motion to the House of Commons to abolish the slave trade, but it was defeated 163 to 88. In 1792 Wilberforce, buttressed by the support of hundreds of thousands of British subjects who had signed petitions favoring the abolition of the slave trade, put forward another motion. However, a compromise measure, supported by Home Secretary Henry Dundas, 1st Viscount Melville, that called for gradual abolition was agreed and passed the House of Commons, much to the disappointment of Wilberforce and his supporters. For the next 15 years, Wilberforce was able to achieve little progress toward ending the slave trade (in part because of the domestic preoccupation with the war against Napoleon).

With the outbreak of war with France, abolition of slave trade became a secondary subject as parliament concentrated on the national crisis situation. Despite lack of interest, Wilberforce continued to introduce abolition bills right through the 1790s. The beginning of the 19th century marked a renewed interest in abolition. In 1804, Clarkson resumed his work and the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade began meeting again, strengthened with prominent new members such as Zachary Macaulay, Henry Brougham, and James Stephen.

In June 1804, Wilberforce yet again introduced a Bill in the House of Common that was successfully passed. However, it failed through the House of Lords. On its reintroduction during the 1805 session, it was defeated, with even the usually sympathetic Pitt failing to support it. On this occasion and throughout the campaign, abolition was held back by Wilberforce’s trusting, even credulous nature, and his deferential attitude towards those in power. He found it difficult to believe that men of rank would not do what he perceived to be the right thing and was reluctant to confront them when they did not.

In 1807, the slave trade was finally abolished, but this did not free those who were already slaves. It was not until 1833 that an act was passed giving freedom to all slaves in the British Empire.

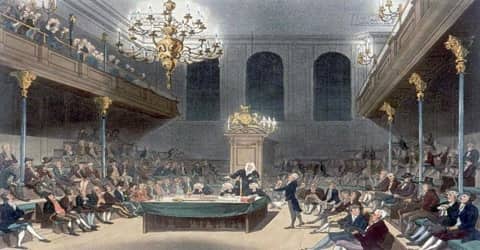

(The House of Commons in Wilberforce’s day by Augustus Pugin and Thomas Rowlandson (1808–1811))

Wilberforce was an ardent supporter of education and believed that education was vital in alleviating poverty from the society. He worked with the reformer, Hannah More to provide children with regular education in reading, personal hygiene, and religion. He was closely involved with the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. He encouraged Christian missionaries to go to India. By 1812, his health deteriorated. He gave up his Yorkshire seat and instead became an MP for rotten borough of Bramber.

In 1823 he aided in organizing and became a vice president of the Society for the Mitigation and Gradual Abolition of Slavery throughout the British Dominions again, more commonly called the Anti-Slavery Society. Turning over to Buxton the parliamentary leadership of the abolition movement, he retired from the House of Commons in 1825.

In 1824, he finally resigned from his parliamentary seat due to serious illness. Retired from political life, he continued to fight for the abandonment of slavery. It was after much debate that the Abolition of Slavery Bill was passed in the House of Commons on July 26, 1833.

Wilberforce’s other efforts to ‘renew society’ included the organization of the Society for the Suppression of Vice in 1802. He worked with the reformer, Hannah More, in the Association for the Better Observance of Sunday. Its goal was to provide all children with regular education in reading, personal hygiene, and religion. He was closely involved with the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. He was also instrumental in encouraging Christian missionaries to go to India.

After Wilberforce’s death in 1833, the Bill was passed in the House of Lords, thus forming the Slavery Abolition Act that came into full effect from August 1834.

Awards and Honor

His life and works have been commemorated worldwide. Statues, busts, and plaques of him adorn different sites. Churches within the Anglican Communion commemorated his work by introducing him in their liturgical calendars. A university in Ohio is named after him. His house in Hull has been converted into Britain’s first slavery museum.

Amazing Grace, a film about Wilberforce and the struggle against the slave trade, directed by Michael Apted and starring Ioan Gruffudd and Benedict Cumberbatch was released in 2007 to coincide with the 200th anniversary of Parliament’s anti-slave trade legislation.

Death and Legacy

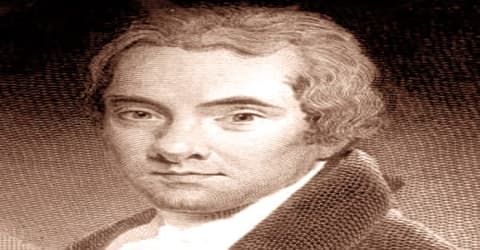

(Wilberforce was buried in Westminster Abbey next to Pitt. This memorial statue, by Samuel Joseph (1791–1850), was erected in 1840 in the north choir aisle.)

In 1833, Wilberforce suffered from a severe attack of influenza from which he never recovered. Just three days after the Bill for Abolition of Slavery was passed in the House of Commons, Wilberforce died on July 29, 1833.

Wilberforce had requested that he was to be buried with his sister and daughter at Stoke Newington, just north of London. However, the leading members of both Houses of Parliament urged that he be honored with a burial in Westminster Abbey. The family agreed and, on 3 August 1833, Wilberforce was buried in the north transept, close to his friend William Pitt the Younger. The funeral was attended by many Members of Parliament, as well as by members of the public. The pallbearers included the Duke of Gloucester, the Lord Chancellor Henry Brougham and the Speaker of the House of Commons Charles Manners-Sutton.

While tributes were paid and Wilberforce was laid to rest, both Houses of Parliament suspended their business as a mark of respect.

Information Source: