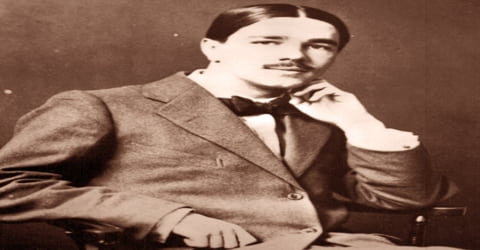

Biography of Wilfred Owen

Wilfred Owen – English poet and soldier.

Name: Wilfred Edward Salter Owen

Date of Birth: 18 March 1893

Place of Birth: Oswestry, Shropshire, England

Date of Death: 4 November 1918 (aged 25)

Place of Death: Sambre–Oise Canal, France

Father: Harold Owen

Mother: Susan Owen

Siblings: Colin, Harold, Mary Millard Owen

Early Life

Wilfred Owen (an English poet and solider) was born on 18 March 1893 at Plas Wilmot, a house in Weston Lane, near Oswestry in Shropshire. His family shuffled between Birkenhead and Shrewsbury during his childhood, and he was educated at the Birkenhead Institute and at Shrewsbury Technical School. Raised as an Anglican, he was a devout believer in his youth. However, he lost faith in the church because of its ceremony and failure to help those in need. He enlisted in the Artists’ Rifles Officers’ Training Corps when war broke out. He trained at Hare Hall Camp in Essex and was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the Manchester Regiment.

Owen was educated at the Birkenhead Institute and matriculated at the University of London; after an illness in 1913, he lived in France. He had already begun to write and, while working as a tutor near Bordeaux, was preparing a book of “Minor Poems in Minor Keys by a Minor,” which was never published. These early poems are consciously modeled on those of John Keats; often ambitious, they show enjoyment of poetry as a craft.

He was one of the leading poets of the First World War. His war poetry on the horrors of trenches and gas warfare was heavily influenced by his mentor Siegfried Sassoon and stood in stark contrast both to the public perception of war at the time and to the confidently patriotic verse written by earlier war poets such as Rupert Brooke. Among his best-known works – most of which were published posthumously – are “Dulce et Decorum est”, “Insensibility”, “Anthem for Doomed Youth”, “Futility”, “Spring Offensive” and “Strange Meeting”.

While attempting to cross the Sambre canal, he was shot and killed. The news of his death arrived at his parents’ house in Shrewsbury on Armistice Day.

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

Wilfred Edward Salter Owen was born Wilfred Edward Salter Owen on March 18, 1893, to Thomas Owen and Harriet Susan Shaw Owen at Oswestry, Shropshire, England. The eldest of four children, his siblings were Harold, Colin, and Mary Millard Owen. When Wilfred was born, his parents lived in a comfortable house owned by his grandfather, Edward Shaw.

After Edward’s death in January 1897, and the house’s sale in March, the family lodged in the back streets of Birkenhead. There Thomas Owen temporarily worked in the town employed by a railway company. Thomas transferred to Shrewsbury in April 1897 where the family lived with Thomas’ parents in Canon Street.

The family then stayed in Birkenhead while Thomas Owen worked with a railway company. His father was transferred to Shrewsbury, during which time the family lived with Thomas’ parents in Canon Street. In 1898, Thomas was transferred back to Birkenhead when he became stationmaster at Woodside station. His family moved homes three successive times in the Tranmere district. They moved back to Shrewsbury in 1907.

Wilfred Owen was educated at the Birkenhead Institute and at Shrewsbury Technical School (later known as the Wakeman School). His last two years of formal education saw him as a pupil-teacher at the Wyle Cop school in Shrewsbury. In 1911 he passed the matriculation exam for the University of London, but not with the first-class honors needed for a scholarship, which in his family’s circumstances was the only way he could have afforded to attend.

In return for free lodging, and some tuition for the entrance exam Owen worked as a lay assistant to the Vicar of Dunsden near Reading, living in the vicarage from September 1911 to February 1913. During this time he attended classes at University College, Reading (now the University of Reading), in botany and later, at the urging of the head of the English Department, took free lessons in Old English. His time spent at Dunsden parish led him to disillusionment with the Church, both in its ceremony and its failure to provide aid for those in need.

Personal Life

Owen’s friends, Robert Graves and Sacheverell Sitwell, have stated that he was homosexual. It has been debated whether Owen had an affair with Scottish writer C. K. Scott-Moncrieff in May 1918.

Career and Works

Owen discovered his poetic vocation in about 1904 during a holiday spent in Cheshire. He was raised as an Anglican of the evangelical type, and in his youth was a devout believer, in part due to his strong relationship with his mother, which lasted throughout his life. His early influences included the Bible and the “big six” of romantic poetry, particularly John Keats.

In 1915 Owen enlisted in the British army. The experience of trench warfare brought him to rapid maturity; the poems were written after January 1917 are full of anger at war’s brutality, an elegiac pity for “those who die as cattle,” and a rare descriptive power. In June 1917 he was wounded and sent home. While in a hospital near Edinburgh he met the poet Siegfried Sassoon, who shared his feelings about the war and who became interested in his work. Reading Sassoon’s poems and discussing his work with Sassoon revolutionized Owen’s style and his conception of poetry.

On 4 June 1916, he was commissioned as a second lieutenant (on probation) in the Manchester Regiment. Initially, Owen held his troops in contempt for their loutish behavior, and in a letter to his mother described his company as “expressionless lumps”. However, his imaginative existence was to be changed dramatically by a number of traumatic experiences. He fell into a shell hole and suffered a concussion; he was blown up by a trench mortar and spent several days unconscious on an embankment lying amongst the remains of one of his fellow officers. Soon afterward, Owen was diagnosed as suffering from neurasthenia or shell shock and sent to Craiglockhart War Hospital in Edinburgh for treatment. It was while recuperating at Craiglockhart that he met fellow poet Siegfried Sassoon, an encounter that was to transform Owen’s life.

Dr. Arthur Brock, at Craiglockhart, advised him to put his war experiences into poetry. He composed poems, including “Futility” and “Strange Meeting”. He made friends with intellectuals and taught at the Tynecastle High School. Owen’s early writing and poetry were initially influenced by the Romantic poets Keats and Shelley. Later, Siegfried Sassoon’s impact can be seen in his poems, “Dulce et Decorum Est” and “Anthem for Doomed Youth”.

Virtually all the poems for which he is now remembered were written in a creative burst between August 1917 and September 1918. His self-appointed task was to speak for the men in his care, to show the ‘Pity of War’, which he also expressed in vivid letters home. His bleak realism, his energy and indignation, his compassion and his great technical skill are evident in many well-known poems, and phrases or lines from his work (“Each slow dusk a drawing-down of blinds” … “The Old Lie: Dulce et decorum est …” ) are frequently quoted.

Owen’s poetry itself underwent significant changes in 1917. As a part of his therapy at Craiglockhart, Owen’s doctor, Arthur Brock, encouraged Owen to translate his experiences, specifically the experiences he relived in his dreams, into poetry. Sassoon, who was becoming influenced by Freudian psychoanalysis, aided him here, showing Owen through example what poetry could do. Sassoon’s use of satire influenced Owen, who tried his hand at writing “in Sassoon’s style”. Further, the content of Owen’s verse was undeniably changed by his work with Sassoon. Sassoon’s emphasis on realism and “writing from experience” was contrary to Owen’s hitherto romantic-influenced style, as seen in his earlier sonnets. Owen was to take both Sassoon’s gritty realism and his own romantic notions and create a poetic synthesis that was both potent and sympathetic, as summarised by his famous phrase “the pity of war”. In this way, Owen’s poetry is quite distinctive, and he is, by many, considered a greater poet than Sassoon. Nonetheless, Sassoon contributed to Owen’s popularity by the strong promotion of his poetry, both before and after Owen’s death, and his editing was instrumental in the making of Owen as a poet.

He wrote a “Preface” for the verses he planned to write. However, the only poems he saw published were those published in The Hydra, the magazine he edited, and “Miners” published in The Nation.

Only five of Owen’s poems were published before his death, one in fragmentary form. His best-known poems include “Anthem for Doomed Youth”, “Futility”, “Dulce Et Decorum Est”, “The Parable of the Old Men and the Young” and “Strange Meeting”. However, most of them were published posthumously: Poems (1920), The Poems of Wilfred Owen (1931), The Collected Poems of Wilfred Owen (1963), The Complete Poems and Fragments (1983); fundamental in this last collection is the poem Soldier’s Dream, that deals with Owen’s conception of war.

Owen’s full unexpurgated opus is in the academic two-volume work The Complete Poems and Fragments (1994) by Jon Stallworthy. Many of his poems have never been published in popular form.

Owen held Siegfried Sassoon in an esteem not far from hero-worship, remarking to his mother that he was “not worthy to light Sassoon’s pipe”. The relationship clearly had a profound impact on Owen, who wrote in his first letter to Sassoon after leaving Craiglockhart “You have fixed my life – however short”. Sassoon wrote that he took “an instinctive liking to him”, and recalled their time together “with affection”. On the evening of 3 November 1917, they parted, Owen, having been discharged from Craiglockhart. He was stationed on home-duty in Scarborough for several months, during which time he associated with members of the artistic circle into which Sassoon had introduced him, which included Robbie Ross and Robert Graves. He also met H. G. Wells and Arnold Bennett, and it was during this period he developed the stylistic voice for which he is now recognized. Many of his early poems were penned while stationed at the Clarence Garden Hotel, now the Clifton Hotel in Scarborough’s North Bay. A blue tourist plaque on the hotel marks its association with Owen.

Wilfred Owen’s reputation has grown steadily, helped over the years by Edmund Blunden’s edition with a biographical memoir in 1931, and by later editions, biographies and critical analyses by C.Day Lewis, Jon Stallworthy, Dominic Hibberd and others. Modern scholarship regards Owen’s work as the most significant poetry to come out of the 1914-1918 war years, and his influence on later generations of poets and readers is widely acknowledged. In 1961 several of his poems were included in Benjamin Britten’s War Requiem.

In 1918, Owen was posted to the Northern Command Depot at Ripon. He led units of the Second Manchesters to storm a number of enemy strong points near the village of Joncourt. Sassoon and Owen kept in touch through correspondence, and after Sassoon was shot in the head in July 1918 and sent back to England to recover, they met in August and spent what Sassoon described as “the whole of a hot cloudless afternoon together.” They never saw each other again. About three weeks later, Owen wrote to bid Sassoon farewell, as he was on the way back to France, and they continued to communicate. After the Armistice, Sassoon waited in vain for word from Owen, only to be told of his death several months later. The loss grieved Sassoon greatly, and he was never “able to accept that disappearance philosophically.”

An important turning point in Owen scholarship occurred in 1987 when the New Statesman published a stinging polemic ‘The Truth Untold’ by Jonathan Cutbill, the literary executor of Edward Carpenter, which attacked the academic suppression of Owen as a poet of homosexual experience. Amongst the points it made was that the poem “Shadwell Stair”, previously alleged to be mysterious, was a straightforward elegy to homosexual soliciting in an area of the London docks once renowned for it.

Awards and Honor

Owen was awarded the Military Cross for his courage and leadership in the Joncourt action. The award was gazetted on 15 February 1919, followed by a citation.

There are memorials to Owen at Gailly, Ors, Oswestry, Birkenhead (Central Library) and Shrewsbury.

On 11 November 1985, Owen was one of the 16 Great War poets commemorated on a slate stone unveiled in Westminster Abbey’s Poet’s Corner. The inscription on the stone is taken from Owen’s “Preface” to his poems: “My subject is War and the pity of War. The Poetry is in the pity.” There is also a small museum dedicated to Owen and Sassoon at the Craiglockhart War Hospital, now a Napier University building.

Death and Legacy

(Owen’s grave, in Ors communal cemetery)

When Owen returned to the Western Front, after more than a year away, he took part in the breaking of the Hindenburg Line at Joncourt (October 1918) for which he was awarded the Military Cross in recognition of his courage and leadership. He was killed on 4 November 1918 during the battle to cross the Sambre-Oise canal at Ors. The news of his death arrived at his parents’ house in Shrewsbury on Armistice Day.

Owen is buried at Ors Communal Cemetery, Ors, in northern France. The inscription on his gravestone, chosen by his mother Susan, is based on a quote from his poetry:

“SHALL LIFE RENEW THESE BODIES? OF A TRUTH ALL DEATH WILL HE ANNUL” W.O…

The forester’s house in Ors, Maison forestière de l’Ermitage, where Owen spent his last night, has been transformed by Simon Patterson into an art installation and permanent memorial to Owen and his poetry.

In 1975, Mrs. Harold Owen, sister-in-law, donated his manuscripts, photographs, and letters to the University of Oxford’s English Faculty Library. The Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, Texas, holds a collection of his family correspondence.

Owen’s poetry has been reworked into various formats. For example, Benjamin Britten incorporated eight of Owen’s poems into his War Requiem, along with words from the Latin Mass for the Dead (Missa pro Defunctis). The Requiem was commissioned for the reconsecration of Coventry Cathedral and first performed there on 30 May 1962. Derek Jarman adapted it for the screen in 1988, with the 1963 recording as the soundtrack.

His poetry is sampled multiple times on the 2000 Jedi Mind Tricks album Violent by Design. Producer Stoupe the Enemy of Mankind has been widely acclaimed for his sampling on the album, and the inclusion of Owen’s poetry.

Information Source: