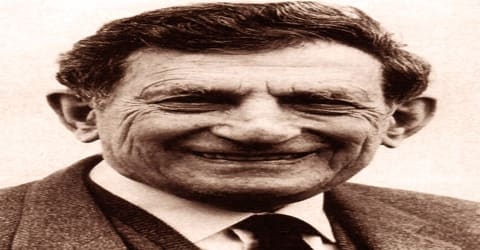

Biography of Wangari Maathai

Wangari Maathai – Kenyan environmental political activist and Nobel laureate.

Name: Wangarĩ Muta Maathai

Date of Birth: 1 April 1940

Place of Birth: Ihithe village, Tetu division, Nyeri District, Kenya (then known as Nyeri, Kenya Colony)

Date of Death: 25 September 2011 (aged 71)

Place of Death: The Nairobi Hospital, Nairobi, Kenya

Occupation: Environmentalist, political activist, writer

Spouse: Mwangi Mathai (m. 1969–1979)

Children: Muta Mathai, Wanjira Mathai, Waweru Mathai

Early Life

Wangari Maathai was a Kenyan environmental political activist and Nobel laureate, was born on April 1, 1940, in Nyeri, Kenya. She was educated in the United States at Mount St. Scholastica (Benedictine College) and the University of Pittsburgh, as well as the University of Nairobi in Kenya.

A Nobel Prize laureate, she was the first African woman and the first environmentalist to be bestowed with the prestigious award. Other than this, she has a number of other firsts to her credit, the foremost being the first African woman to be awarded with a doctorate degree. It was her excellent academic background and great skills that earned her prestigious positions at the University of Nairobi. It was in the 1970s that she founded the Green Belt Movement, which involved planting trees to conserve the environment. With time, the non-government organization expanded and focussed on environmental conservation and women’s rights as well.

In 1977, Maathai founded the Green Belt Movement, an environmental non-governmental organization focused on the planting of trees, environmental conservation, and women’s rights. In 1984, she was awarded the Right Livelihood Award, and in 2004, she became the first African woman to receive the Nobel Peace Prize for “her contribution to sustainable development, democracy and peace.” She was an Honorary Councillor of the World Future Council. She was affiliated to professional bodies and received several awards.

Towards the latter half of her life, she became a political activist. She was elected as a Member of Parliament and served as assistant minister for Environment and Natural Resources in the government of President Mwai Kibaki from January 2003 and November 2005. In 2006, France bestowed upon her one of its highest decorations, Legion d’honneur. In 2011, Maathai died of complications from ovarian cancer.

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

Wangari Maathai, in full Wangari Muta Maathai, was born April 1, 1940, in the village of Ihithe, Nyeri District, in the central highlands of the colony of Kenya. Her family was Kikuyu, the most populous ethnic group in Kenya, and had lived in the area for several generations. Around 1943, Maathai’s family relocated to a White-owned farm in the Rift Valley, near the town of Nakuru, where her father had found work.

Maathai’s home life was very much like other Kenyans in other ways as well. Her father was considered the head of the house; her mother had very little power and performed traditional “women’s tasks” such as fetching water and gathering firewood. In particular, education for women and girls was not valued, or even encouraged. But Maathai was extremely bright, and her older brother persuaded their parents to send her to school when she was seven years old.

In 1947, Maathai returned to Ihithe, for lack of educational opportunities at the farm. At the age of eight, she enrolled at the Ihithe Primary School and within three years, moved to St. Cecilia’s Intermediate Primary School. It was during her years at St Cecilia that she became fluent in English and converted to Catholicism, thus taking up the surname Maathai.

Studying at St. Cecilia’s, she was sheltered from the ongoing Mau Mau uprising, which forced her mother to move from their homestead to an emergency village in Ihithe. When she completed her studies there in 1956, she was rated first in her class and was granted admission to the only Catholic high school for girls in Kenya, Loreto High School in Limuru.

Completing her preliminary education with the top grade in 1956, she gained admission at Loreto High School. In 1960, she was one of the 300 promising students selected to study in the United States. She gained admission at Mount St. Scholastica College in Kansas, wherein she majored in biology. Finishing her BSc in 1964, she enrolled at the University of Pittsburgh to get an MSc in biology, which she attained in 1966. She was appointed to a position as research assistant to a professor of zoology at University College of Nairobi.

In 1967, at the urging of Professor Hofmann, she traveled to the University of Giessen in Germany in pursuit of a doctorate. She studied both at Giessen and the University of Munich.

In the spring of 1969, she returned to Nairobi to continue studies at the University College of Nairobi as an assistant lecturer.

During her tenure at the university, she was first exposed to environmental restoration by a group of environmentalists who were looking to free the city from air pollution.

In 1971, Maathai became the first Eastern African woman to receive a PhD, her doctorate in veterinary anatomy, from the University College of Nairobi, which became the University of Nairobi the following year. She completed her dissertation on the development and differentiation of gonads in bovines. She began teaching in the Department of Veterinary Anatomy at the University of Nairobi after graduation, and in 1977 she became chair of the department.

Personal Life

In April 1966, Wangari met Mwangi Mathai, another Kenyan who had studied in America. She married Mwangi Mathai, in May 1969. The couple was blessed with three children. They parted ways in 1977 which was followed by a legal separation in 1979. Mwangi was said to have believed Wangari was “too strong-minded for a woman” and that he was “unable to control her”.

The divorce had been costly, and with lawyers’ fees and the loss of her husband’s income, Maathai found it difficult to provide for herself and her children on her university wages. An opportunity arose to work for the Economic Commission for Africa through the United Nations Development Programme. As this job required extended travel throughout Africa and was based primarily in Lusaka, Zambia, she was unable to bring her children with her. Maathai chose to send them to her ex-husband and take the job. While she visited them regularly, they lived with their father until 1985.

Career and Works

Concluding her studies, Wangari Maathai returned to Kenya to take up the seat of a research assistant to a professor of zoology at the University College of Nairobi. However, the post was transferred to someone else due to gender and tribal biasness. She finally found work under Professor Reinhold Hofmann in the microanatomy section of the newly established Department of Veterinary Anatomy in the School of Veterinary Medicine at University College of Nairobi.

Maathai was the first woman in Nairobi appointed to any of these positions. During this time, she campaigned for equal benefits for the women working on the staff of the university, going so far as trying to turn the academic staff association of the university into a union, in order to negotiate for benefits. The courts denied this bid, but many of her demands for equal benefits were later met. In addition to her work at the University of Nairobi, Maathai became involved in a number of civic organizations in the early 1970s. She was a member of the Nairobi branch of the Kenya Red Cross Society, becoming its director in 1973. She was a member of the Kenya Association of University Women.

Her career graph witnessed an upward drift in the following years, as she first became a senior lecturer in anatomy, later on taking up the chair of the Department of Veterinary Anatomy and finally becoming an associate professor in 1977. It was while holding on to these significant positions that she fought against gender and tribal biasness, strongly raising her voice for equal rights of women.

While working with the National Council of Women of Kenya, Maathai developed the idea that village women could improve the environment by planting trees to provide a fuel source and to slow the processes of deforestation and desertification. The Green Belt Movement, an organization she founded in 1977, had by the early 21st century planted some 30 million trees. Leaders of the Green Belt Movement established the Pan African Green Belt Network in 1986 in order to educate world leaders about conservation and environmental improvement. As a result of the movement’s activism, similar initiatives were begun in other African countries, including Tanzania, Ethiopia, and Zimbabwe.

In 1974, Maathai’s family expanded to include her third child, son Muta. Her husband campaigned again for a seat in Parliament, hoping to represent the Lang’ata constituency, and won. During his campaign, he had promised to find jobs to limit the rising unemployment in Kenya. These promises led Maathai to connect her ideas of environmental restoration to providing jobs for the unemployed and led to the founding of Envirocare Ltd., a business that involved the planting of trees to conserve the environment, involving ordinary people in the process. This led to the planting of her first tree nursery, collocated with a government tree nursery in Karura Forest. Envirocare ran into multiple problems, primarily dealing with funding. The project failed. However, through conversations concerning Envirocare and her work at the Environment Liaison Centre, UNEP made it possible to send Maathai to the first UN conference on human settlements, known as Habitat I, in June 1976.

Returning to Nairobi, she promoted her idea of planting trees at the National Council of Women of Kenya (NCWK). Accepting the idea, the council led a procession on June 5, 1977 planting seven trees. Formerly known as ‘Save the Land Harambee’, it later became popular as Green Belt Movement.

Considering how enormous the issues were, Maathai felt that an immediate and straightforward plan was needed. She came up with a simple solution: plant trees. As Maathai explained to Michelle Martin of Catholic New World, “It occurred to me that some of the problems women talked about were connected to the land. If you plant trees you give them firewood. If you plant trees you give them food.” On Earth Day in 1977, Maathai put her plan into action by planting seven trees to honor Kenyan women environmental leaders. (Earth Day is an annual day set aside to honor and celebrate the environment.) Later that year, with backing from the National Council of Women, the budding environmentalist quit teaching and formed the Green Belt Movement. The group started small, with only a handful of villagers gathering seeds and planting them.

As the Green Belt Movement expanded, Maathai found herself increasingly at odds with the Kenyan government. She explained to Amitabh Pal of the Progressive, “I started seeing the linkages between the problems that we were dealing with and the root causes…. I knew that a major culprit of environmental destruction was the government.” Maathai became an outspoken advocate for environmental policy reform; she also held seminars to educate citizens that they must hold government officials accountable for managing natural resources. One of the first public confrontations came in 1989 when Maathai openly protested the building of a $200 million, sixty-story skyscraper in Nairobi’s Uhuru Park that was slated to be used for government offices. Maathai’s campaign was so successful that the building was never constructed.

With greater popularity, the Green Belt Movement expanded throughout Africa and founded the Pan-African Green Belt Network. It transformed to become a separate non-government organization and aimed to combat issues such as desertification, deforestation, water crises, and rural hunger.

In her 2010 book, Replenishing the Earth: Spiritual Values for Healing Ourselves and the World, she discussed the impact of the Green Belt Movement, explaining that the group’s civic and environmental seminars stressed “the importance of communities taking responsibility for their actions and mobilizing to address their local needs,” and adding, “We all need to work hard to make a difference in our neighborhoods, regions, and countries, and in the world as a whole. That means making sure we work hard, collaborate with each other, and make ourselves better agents to change.”

In 1979, she contested for the position of a chairman at the NCWK. She lost by three votes and was eventually given the seat of vice chairman. Following year, she won an unopposed election and was chosen as the chairman, a position she retained until 1987. Despite immense financial problems, the organization gained worldwide fame for its environmental friendly work.

Towards the latter half of the 1980s, she started pressing for democracy, constitutional reform and freedom of expression. This did not go down well with the government which forced her to vacate the office

In 1982, the Parliamentary seat representing her home region of Nyeri was open, and Maathai decided to campaign for the seat. As required by law, she resigned her position with the University of Nairobi to campaign for office. The courts decided that she was ineligible to run for office because she had not re-registered to vote in the last presidential election in 1979. Maathai believed this to be false and illegal and brought the matter to court. The court was to meet at nine in the morning, and if she received a favorable ruling, was required to present her candidacy papers in Nyeri by three in the afternoon that day. The judge disqualified her from running on a technicality. When she requested her job back, she was denied. As she lived in university housing and was no longer a staff member, she was evicted.

In a series of events that followed, she launched a hunger strike to liberate political prisoners. Though the government did not bow down to the demands initially, they eventually surrendered and the prisoners were freed in 1993. With an attempt to defeat the ruling party and bring down President Arap Moi from his chair, she twice attempted to unite the opposition, but in vain. As a result, in 1997, she ran for the seat of the president as a candidate of the Liberal Party but lost it.

On 28 February 1992, while released on bail, Maathai and others took part in a hunger strike in a corner of Uhuru Park, which they labeled Freedom Corner, to pressure the government to release political prisoners. After four days of hunger strike, on 3 March 1992, the police forcibly removed the protesters. Maathai and three others were knocked unconscious by police and hospitalized. President Daniel Arap Moi called her “a mad woman” and “a threat to the order and security of the country”. The attack drew international criticism. The US State Department said it was “deeply concerned” by the violence and by the forcible removal of the hunger strikers. When the prisoners were not released, the protesters – mostly mothers of those in prison – moved their protest to All Saints Cathedral, the seat of the Anglican Archbishop in Kenya, across from Uhuru Park. The protest there continued, with Maathai contributing frequently, until early 1993, when the prisoners were finally released.

In addition to her conservation work, Maathai was also an advocate for human rights, AIDS prevention, and women’s issues, and she frequently represented these concerns at meetings of the United Nations General Assembly. She was elected to Kenya’s National Assembly in 2002 with 98 percent of the vote, and in 2003 she was appointed an assistant minister of environment, natural resources, and wildlife. When she won the Nobel Prize in 2004, the committee commended her “holistic approach to sustainable development that embraces democracy, human rights, and women’s rights in particular.”

In 2005, Maathai was integral in helping to shape Kenya’s new Bill of Rights; she also represented Kenya at the 2005 United Nations Commission on the Status of Women, an international body of representatives convened to promote the rights of women worldwide. In addition, Maathai continued in her role as an internationally recognized environmentalist. By late 2005, through the Pan-African Green Belt Network, over fifteen African countries had become involved with the Green Belt Movement. The movement also spread beyond the African borders to the United States, where representatives work through the Friends of the Greenbelt Movement North America. In 2005 a primary goal of Maathai was to extend the resources of the Green Belt Movement to help other areas of the world, such as the Republic of Haiti, which has also been ravaged by deforestation.

In 2007, Maathai was defeated in the Party of National Unity’s primary elections for its parliamentary candidates. Choosing to run as a candidate of a smaller party, she was later defeated yet again in the December 2007 parliamentary elections.

Her first book, The Green Belt Movement: Sharing the Approach and the Experience (1988; rev. ed. 2003), detailed the history of the organization. She published an autobiography, Unbowed, in 2007. Another volume, The Challenge for Africa (2009), criticized Africa’s leadership as ineffectual and urged Africans to try to solve their problems without Western assistance. Maathai was a frequent contributor to international publications such as the Los Angeles Times and the Guardian.

On 28 March 2005, Maathai was elected the first president of the African Union’s Economic, Social and Cultural Council and was appointed a goodwill ambassador for an initiative aimed at protecting the Congo Basin Forest Ecosystem. In 2006, she was one of the eight flag-bearers at the 2006 Winter Olympics Opening Ceremony. Also on 21 May 2006, she was awarded an honorary doctorate by and gave the commencement address at Connecticut College. Maathai was one of the founders of the Nobel Women’s Initiative along with sister Nobel Peace laureates Jody Williams, Shirin Ebadi, Rigoberta Menchú Tum, Betty Williams and Mairead Corrigan Maguire. Six women representing North America and South America, Europe, the Middle East and Africa decided to bring together their experiences in a united effort for peace with justice and equality. It is the goal of the Nobel Women’s Initiative to help strengthen work being done in support of women’s rights around the world.

Awards and Honor

In 1991, Maathai received the Goldman Environmental Prize in San Francisco and the Hunger Project’s Africa Prize for Leadership in London.

Wangarĩ Maathai was awarded the 2004 Nobel Peace Prize for her “contribution to sustainable development, democracy, and peace”. She became the first African woman, and the first environmentalist, to win the prize.

Maathai was bestowed with one of France’s most honorable decorations, Legion d’honneur, in 2006.

She was awarded two honorary degrees, Doctor of Public Service by the University of Pittsburgh in 2006 and Doctor of Science by Syracuse University posthumously in 2013.

The 2017 award was presented at the 4th Global Landscapes Forum (GLF) in Bonn, Germany, 19–20 December 2017 to Maria Margarida Ribeiro da Silva. Maria Margarida Ribeiro da Silva, a Brazilian forestry activist, was awarded the Wangarĩ Maathai Forest Champion Award for her achievements in promoting community forest management and improving the quality of life for many Amazonian communities. In addition to being awarded the 2017 Wangarĩ Maathai Forest Champion Award, Ribiero da Silva also received a cash prize of $20,000 USD.

Death and Legacy

(Wangarĩ Maathai memorial trees and garden at the University of Pittsburgh)

Wangarĩ Maathai died on 25 September 2011 of complications arising from ovarian cancer while receiving treatment at a Nairobi hospital. A year after her death, Wangari Maathai Award was inaugurated to honor and commemorate an extraordinary woman who championed forest issues around the world.

On April 1, 2013, marking her 73rd birthday, she was posthumously honored with a Google Doodle.

Information Source: