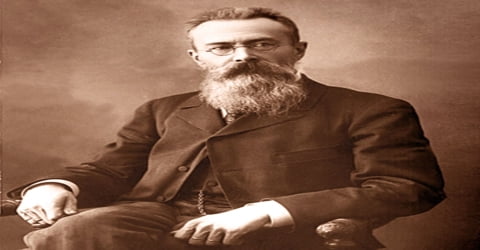

Biography of Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov

Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov – Russian composer.

Name: Nikolai Andreyevich Rimsky-Korsakov

Date of Birth: March 18, 1844

Place of Birth: Tikhvin, Russia

Date of Death: June 21, 1908

Place of Death: Lyubensk, Russia

Occupation: Composer

Father: Andrei Petrovich Rimsky-Korsakov

Mother: Sofya Vasilievna Rimskaya-Korsakova

Spouse/Ex: Nadezhda Rimskaya-Korsakova (m. 1872–1908)

Early Life

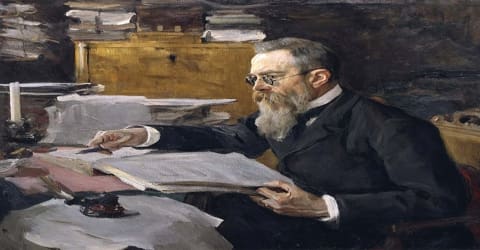

Of all the great Russian nationalist composers of the latter part of the 19th century, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov was born on March 18, 1844, in Tikhvin, 200 kilometers (120 mi) east of Saint Petersburg, into a Russian noble family. He was a Russian composer, teacher, and editor who was at his best in descriptive orchestrations suggesting a mood or a place. He was a master of orchestration. His best-known orchestral compositions Capriccio Espagnol, the Russian Easter Festival Overture and the symphonic suite Scheherazade are staples of the classical music repertoire, along with suites and excerpts from some of his 15 operas. Scheherazade is an example of his frequent use of fairy tale and folk subjects.

Although Rimsky had a naval background, he had a great passion for music. Some of his famous compositions were the popular symphonies such as ‘Scheherazade’, ‘Russian Easter Festival Overture’ and ‘Capriccio Espagnol’. He also had a wide opus that included his unique chamber works, operas, and orchestrations. He believed, as did fellow composer Mily Balakirev and critic Vladimir Stasov, in developing a nationalistic style of classical music. This style employed Russian folk song and lore along with exotic harmonic, melodic and rhythmic elements in a practice known as musical orientalism, and eschewed traditional Western compositional methods.

Rimsky’s music touched hearts worldwide and his works were noted and followed by many Russian and non-Russian composers alike. Encouraged and pushed by a certain Mily Balakirev, he went on to refine and develop his interest for composition and varied music. It is through this person that he also met four other talented composers, who would, later, go on to become a part of a big venture called the ‘Five.’ Rimsky’s music inspired a long list of composers such as Claude Debussy and went on to cultivate and encourage future talents for generations to come.

Mainly known for his symphonic works, especially the popular symphonic suite Sheherazade, as well as the Capriccio Espagnol and the Russian Easter Festival Overture, Rimsky-Korsakov left an oeuvre that also included operas, chamber works, and songs. Rimsky-Korsakov’s music is accessible and engaging owing to his talent for tone-coloring and brilliant orchestration. Furthermore, his operas are masterful musical evocations of myths and legends.

For much of his life, Rimsky-Korsakov combined his composition and teaching with a career in the Russian military at first as an officer in the Imperial Russian Navy, then as the civilian Inspector of Naval Bands. He wrote that he developed a passion for the ocean in childhood from reading books and hearing of his older brother’s exploits in the navy. This love of the sea may have influenced him to write two of his best-known orchestral works, the musical tableau Sadko (not to be confused with his later opera of the same name) and Scheherazade. Through his service as Inspector of Naval Bands, Rimsky-Korsakov expanded his knowledge of woodwind and brass playing, which enhanced his abilities in orchestration. He passed this knowledge to his students, and also posthumously through a textbook on orchestration that was completed by his son-in-law, Maximilian Steinberg.

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov, in full Nikolay Andreyevich Rimsky-Korsakov, was born on 18th March 1844, in the quaint town of Tikhvin, to a Russian aristocrat family. He was the second son of a substantial landowner who lived “in his own house” on the outskirts of a small town, Tikhvin. Both his parents were musical and were quick to perceive that their son was unusually gifted; he had perfect pitch and excellent time and by the age of 6 he was having music lessons but was not sufficiently enamored of music for it to supersede his love of books.

Everyone in the family either had an army or a naval background and Rimsky’s brother, 22 years his senior, was a sea explorer and navigator. Rimsky’s mother was a piano player herself and his father could play the piano by listening to the notes. Rimsky believed that he inherited his mother’s quality of playing and learning slowly. He had an inherent quality and liking for music but never believed that he could make it his forte.

In 1856 Rimsky was sent to the Naval College in St. Petersburg where he spent the next four years. He also began to go to the opera in St. Petersburg; struck first by Gaetano Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor and Robert le Diable, he later discovered the joys of harmony through playing manuscripts of Mikhail Glinka’s Ruslan and Lyudmila and began making his own piano arrangements of excerpts from a range of favorite operas.

However, Rimsky never discontinued his piano lessons. During his tenure at the school, Rimsky was trained by a well-known, local teacher ‘Ulikh’ who inculcated and nurtured Rimsky’s interest in music. He was impressed by Rimsky’s talent and recommended him to another teacher called Kanille who introduced Rimsky to Mily Balakirev, the man responsible for Rimsky’s tremendous and successful musical career.

Personal Life

(Nadezhda Purgold)

In December 1871 Rimsky proposed to Nadezhda Purgold, with whom he had developed a close relationship over weekly gatherings of The Five at the Purgold household. They married in July 1872, with Mussorgsky serving as best man. The Rimsky-Korsakovs had seven children.

Career and Works

In 1862, after graduating from the naval school, Rimsky-Korsakov was at sea for two and a half years, devoting his free time to composition. Upon Rimsky-Korsakov’s return to St. Petersburg, in 1865, Balakirev conducted his friend’s First Symphony, which was hailed as the first important symphonic work by a Russian composer.

In November 1861, Kanille introduced the 18-year-old Nikolai to Mily Balakirev. Balakirev, in turn, introduced him to César Cui and Modest Mussorgsky; all three were known as composers, despite only being in their 20s. Rimsky-Korsakov later wrote, “With what delight I listened to real business discussions Rimsky-Korsakov’s emphasis on instrumentation, part writing, etc! And besides, how much talking there was about current musical matters! All at once I had been plunged into a new world, unknown to me, formerly only heard of in the society of my dilettante friends. That was truly a strong impression.” Balakirev encouraged Rimsky-Korsakov to compose and taught him the rudiments when he was not at sea. Balakirev prompted him to enrich himself in history, literature, and criticism. When he showed Balakirev the beginning of a symphony in E-flat minor that he had written, Balakirev insisted he continues working on it despite his lack of formal musical training.

On his return to St. Petersburg, Rimsky-Korsakov completed the symphony begun before his voyage, and it was performed with gratifying success in St. Petersburg on December 31, 1865, when the composer was only 21 years old. His next important work was Fantasy on Serbian Themes for orchestra, first performed at a concert of Slavonic music conducted by Balakirev in St. Petersburg, on May 24, 1867.

Balakirev began to get very critical and Rimsky, finding the behavior very restraining, eventually broke loose from Balakirev but always remembered him fondly as the one who nurtured his talent and cultivated his passion. It was during this time he completed his other famous works including ‘Overture on three Russian themes’ and began to perform with the other reputed musicians who then collectively went on to be known as the ‘Five’. Borodin, Cui, Mussorgsky, Balakirev, and Rimsky believed in ‘nationalistic’ music, free from the clasps of the western ways and methods. Out of the five, Rimsky was given a lot of importance and held a special place because of his knowledge in various fields of music and his sheer talent in the field of ‘Operas and Orchestration’. He was particularly acclaimed for his work for the ‘Stone guest’ and ‘Maid of Pskov’.

Rimsky-Korsakov himself was only too aware of his own shortcomings, and his orchestral works at this time tended to be quite short – the Overture on Russian Themes (1866) was given a successful performance in the same year, while 1867’s Sadko, taken over from Mussorgsky who had abandoned an earlier attempt to set the subject to music, was a short and brilliant exposition of memorable melodies, showing real flair in the orchestration – a talent for which he would later become world famous. His Second Symphony, subtitled Antar, was completed in 1868.

In 1871 Rimsky-Korsakov was appointed a professor of composition and orchestration at the St. Petersburg Conservatory. The following year, he married Nadezhda Purgold, a pianist. In 1873, Rimsky-Korsakov left active duty, becoming inspector of navy orchestras, a job which he held until 1884.

Rimsky-Korsakov eventually became an excellent teacher and a fervent believer in academic training. He revised everything he had composed prior to 1874, even acclaimed works such as Sadko and Antar, in a search for perfection that would remain with him throughout the rest of his life. Assigned to rehearse the Orchestra Class, he mastered the art of conducting. Dealing with orchestral textures as a conductor, and making suitable arrangements of musical works for the Orchestra Class, led to an increased interest in the art of orchestration, an area into which he would further indulge his studies as Inspector of Navy Bands. The score of his Third Symphony, written just after he had completed his three-year program of self-improvement, reflects his hands-on experience with the orchestra.

In his autobiographical Chronicle of My Musical Life (1972, originally published in Russian, 1909) he frankly admitted his lack of qualifications for this important position; he himself had never taken a systematic academic course in musical theory, even though he had profited from Balakirev’s desultory instruction and by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s professional advice. Eager to complete his own musical education, he undertook in 1873 an ambitious program of study, concentrating mainly on counterpoint and the fugue. He ended his studies in 1875 by sending 10 fugues to Tchaikovsky, who declared them impeccable.

The composer’s life was filled with many saddening moments from 1875-1885. Just as he was working and refurbishing his dead friend, Mussorgsky’s works, another team member died. He pledged to finish their unfinished scripts and orchestrated, rewrote and completed the famous works such as ‘Khovanshchina’ and ‘Prince Igor’. Even while he was at the pinnacle of success and went on to complete his flag-bearer works such as “Scheherazade” and the “Spanish Capriccio”, he went into a phase of disconsolateness following the deaths of his near and dear ones, including his mentor, Tchaikovsky, who died in 1893. Rimsky continued with his elaborate labyrinth of songs and compositions and successfully completed another Gogol opera, ‘Christmas Eve’, and went on to produce story-heavy compositions such as ‘The Tsar’s Bride’, ‘The legend of the invisible city of Kitezh’ and, the famous, ‘Sadko’. Most of his compositions of the time were distinguished by elegance and Russian poetic rhythm.

Rimsky-Korsakov served as conductor of concerts at the court chapel from 1883 to 1894 and was chief conductor of the Russian symphony concerts between 1886 and 1900. In 1889 he led concerts of Russian music at the Paris World Exposition, and in the spring of 1907, he conducted in Paris two Russian historic concerts in connection with Serge Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes.

Rimsky-Korsakov wrote that May Night was of great importance because, despite the opera’s containing a good deal of contrapuntal music, he nevertheless “cast off the shackles of counterpoint emphasis Rimsky-Korsakov”. He wrote the opera in a folk-like melodic idiom and scored it in a transparent manner much in the style of Glinka. Nevertheless, despite the ease of writing this opera and the next, The Snow Maiden, from time to time he suffered from creative paralysis between 1881 and 1888. He kept busy during this time by editing Mussorgsky’s works and completing Borodin’s Prince Igor (Mussorgsky died in 1881, Borodin in 1887).

In 1883 the new Tzar, Alexander III, dismissed the old chapel musicians and appointed Balakirev as the new superintendent of the Court Chapel and Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov as his aide. This led both of them into utterly unfamiliar territory, preparing choral music for the coronation and other important occasions. A favorite new prodigy, Alexander (“Sasha”) Glazunov, was the young composer-acolyte who came to Rimsky-Korsakov’s aid in 1886 when the sudden death of Borodin left him with yet another disorganized heap of priceless unfinished compositions to put in order. Their major achievements were the performing version of Prince Igor and the realization of Borodin’s unfinished Third Symphony, one movement of which Glazunov wrote down apparently from memory, having once heard Borodin play it on the piano.

In 1895, Rimsky-Korsakov’s Christmas Eve, another opera after a Gogol story, was produced. The composer’s subsequent works recreated the rich world of Russian myths and legends. Sadko, completed in 1896, conjured up a medieval Russian legend. In 1901, Rimsky-Korsakov blended the legend of Kitezh and the story of St. Fevroniya to create a complex Christian-pantheistic narrative. Completed in 1905, the year when the politically progressive composer was temporarily dismissed from this teaching post, The Legend of the Invisible City of Kitezh and the Maiden, was produced in 1907.

Rimsky-Korsakov’s edited and altered version of Boris Godunov evoked sharp criticism from modernists who venerated Mussorgsky’s originality, but Rimsky-Korsakov’s intervention vouchsafed the opera’s survival. Mussorgsky’s score was later published in 1928 and had several performances in Russia and abroad, but ultimately the more effective Rimsky-Korsakov version prevailed in opera houses. Rimsky-Korsakov also edited (with the composer Aleksandr Glazunov) the posthumous works of Borodin.

With Piotr Ilyitch Tchaikovsky, Mussorgsky and Borodin all dead, Rimsky-Korsakov was unchallenged as the leading living Russian composer and used his position both to promote his own operas and to forward the career of those composers in whose talents he firmly believed, such as Glazunov. Buoyed by the relative ease of his composition of Christmas Eve, Rimsky-Korsakov next plunged into the legend of Sadko, completing an opera on it in 1896. It is in many ways his most accomplished opera and was very popular during his lifetime. After this, there was seldom a period when he was not devising, or working upon, his next opera, with The Tsar’s Bride and Mozart and Salieri both, completed before the end of the decade. With the opening of the new century, The Tale of Tsar Sultan was produced privately in St. Petersburg.

The success of Rimsky-Korsakov’s Christmas Eve encouraged him to complete an opera approximately every 18 months between 1893 and 1908 a total of 11 during this period. He also started and abandoned another draft of his treatise on orchestration, but made a third attempt and almost finished it in the last four years of his life. His son-in-law Maximilian Steinberg completed the book in 1912. Rimsky-Korsakov’s scientific treatment of orchestration, illustrated with more than 300 examples from his work, set a new standard for texts of its kind.

In the next decade operas such as Pan Voyevoda (1903), Kastchei. The Immortal (1902), the dramatic prologue Vera Sheloga (starring the great bass Chaliapin), the mystical and extraordinary opera The Legend of the Invisible City of Kitezh (1905), and The Golden Cockerel all appeared. During these years Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov kept a high public profile, culminating in open discord with the St. Petersburg Conservatory when students in 1905 rebelled against what they saw as an oppressive and conservative musical autocracy.

In 1905, demonstrations took place in the St. Petersburg Conservatory as part of the 1905 Revolution; these, Rimsky-Korsakov wrote, were triggered by similar disturbances at St. Petersburg State University, in which students demanded political reforms and the establishment of a constitutional monarchy in Russia. “I was chosen a member of the committee for adjusting differences with agitated pupils”, he recalled; almost as soon as the committee had been formed, “all sorts of measures were recommended to expel the ringleaders, to quarter the police in the Conservatory, to close the Conservatory entirely”.

Rimsky-Korsakov’s last opera, The Golden Cockerel, completed in 1907, was inspired by a politically subversive story by Alexander Pushkin. The production of this work was a struggle because the subject matter aroused suspicions among government censors. The opera was finally produced, in 1909, the year following the composer’s death, by a private opera company in Moscow.

The following year, his opera Sadko was produced at the Paris Opéra and The Snow Maiden at the Opéra-Comique. He also had the opportunity to hear more recent music by European composers. He hissed unabashedly when he heard Richard Strauss’s opera Salome, and told Diaghilev after hearing Claude Debussy’s opera Pelléas et Mélisande, “Don’t make me listen to all these horrors or I shall end up liking them!” Hearing these works led him to appreciate his place in the world of classical music. He admitted that he was a “convinced kuchkist” (after kuchka, the shortened Russian term for The Five) and that his works belonged to an era that musical trends had left behind.

Rimsky-Korsakov was at his best and most typical in his descriptive works. With two exceptions (Servilia (1902) and Mozart and Salieri (1898)), the subjects of Rimsky-Korsakov’s operas are taken from Russian or other Slavic fairy tales, literature, and history. These include Snow Maiden (1882), Sadko, The Tsar’s Bride (1899), The Tale of Tsar Saltan, The Legend of the Invisible City of Kitezh and the Maiden Fevronia, and Le Coq d’Or (1909). Although these operas are part of the regular repertory in Russian opera houses, they are rarely heard abroad; only Le Coq d’Or enjoys occasional production in Western Europe and the United States.

He went on to inspire two generations of music. His works had a touch of magic-realism and were heavily influenced by the music created by ‘Five’. He had many religious, liturgical, oriental and folk themes incorporated in his various styles of music and was very critical of his own music. He worked, reworked and, even, scrapped pieces he felt were not up to standards. Rimsky explored with harmonies, rhythms and was brave enough to cut off from total westernization while cleverly incorporating its styles with traditional, or as he called it, ‘nationalistic’ music.

Death and Legacy

At the start of 1890, Rimsky began to develop angina problems and he succumbed to the illness on 8th June 1908. In 1908, he died at his Lubensk estate near Luga (modern-day Plyussky District of Pskov Oblast) and was interred in Tikhvin Cemetery at the Alexander Nevsky Monastery in Saint Petersburg, next to Borodin, Glinka, Mussorgsky, and Stasov.

His death left behind a long list of followers who were moved and inspired by his radical music. Even though he faced countless struggles and oppression during his productions, he continued to make daring and, at times, conservative musical harmonies that even evoked government restrictions and censorship.

Of the composer’s orchestral works, the best known are Capriccio Espagnol (1887), the symphonic suite Scheherazade, and Russian Easter Festival (1888) overture. “The Flight of the Bumble Bee” from The Tale of Tsar Saltan and the “Song of India” from Sadko are perennial favorites in a variety of arrangements.

While Rimsky-Korsakov is best known in the West for his orchestral works, his operas are more complex, offering a wider variety of orchestral effects than in his instrumental works and fine vocal writing. Excerpts and suites from them have proved as popular in the West as the purely orchestral works. The best-known of these excerpts is probably “Flight of the Bumblebee” from The Tale of Tsar Saltan, which has often been heard by itself in orchestral programs, and in countless arrangements and transcriptions, most famously in a piano version made by Russian composer Sergei Rachmaninoff. Other selections familiar to listeners in the West are “Dance of the Tumblers” from The Snow Maiden, “Procession of the Nobles” from Mlada, and “Song of the Indian Guest” (or, less accurately, “Song of India”) from Sadko, as well as suites from The Golden Cockerel and The Legend of the Invisible City of Kitezh and the Maiden Fevroniya.

Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov also wrote a piano concerto. As a professor of composition and orchestration at the St. Petersburg Conservatory from 1871 until the end of his life (with the exception of a brief period in 1905 when he was dismissed by the reactionary directorate for his defense of students on strike), he taught two generations of Russian composers, and his influence, therefore, was pervasive. Igor Stravinsky studied privately with him for several years. His Practical Manual of Harmony (1884) and Fundamentals of Orchestration (posthumous, 1913) are still used as basic musical textbooks in Russia.

Information Source: